Difference between revisions of "User:Jhurley/sandbox"

(→Introduction) |

(→Heating Method) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | ==PFAS Soil | + | ==Thermal Conduction Heating for Treatment of PFAS-Impacted Soil== |

| − | [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] | + | Removal of [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] compounds from impacted soils is challenging due to the modest volatility and varying properties of most PFAS compounds. Thermal treatment technologies have been developed for treatment of semi-volatile compounds in soils such as dioxins, furans, poly-aromatic hydrocarbons and poly-chlorinated biphenyls at temperatures near 325°C. In controlled bench-scale testing, complete removal of targeted PFAS compounds to concentrations below reporting limits of 0.5 µg/kg was demonstrated at temperatures of 400°C<ref name="CrownoverEtAl2019"> Crownover, E., Oberle, D., Heron, G., Kluger, M., 2019. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances thermal desorption evaluation. Remediation Journal, 29(4), pp. 77-81. [https://doi.org/10.1002/rem.21623 doi: 10.1002/rem.21623]</ref>. Three field-scale thermal PFAS treatment projects that have been completed in the US include an in-pile treatment demonstration, an ''in situ'' vadose zone treatment demonstration and a larger scale treatment demonstration with excavated PFAS-impacted soil in a constructed pile. Based on the results, thermal treatment temperatures of at least 400°C and a holding time of 7-10 days are recommended for reaching local and federal PFAS soil standards. The energy requirement to treat typical wet soil ranges from 300 to 400 kWh per cubic yard, exclusive of heat losses which are scale dependent. Extracted vapors have been treated using condensation and granular activated charcoal filtration, with thermal and catalytic oxidation as another option which is currently being evaluated for field scale applications. Compared to other options such as soil washing, the ability to treat on site and to treat all soil fractions is an advantage. |

<div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | ||

'''Related Article(s):''' | '''Related Article(s):''' | ||

| − | * [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] | + | *[[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] |

| − | * [[ | + | *[[Thermal Conduction Heating (TCH)]] |

| − | |||

| − | ''' | + | '''Contributors:''' Gorm Heron, Emily Crownover, Patrick Joyce, Ramona Iery |

| − | '''Key Resource | + | '''Key Resource:''' |

| − | + | *Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances thermal desorption evaluation<ref name="CrownoverEtAl2019"/> | |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

| − | PFAS | + | [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] have become prominent emerging contaminants in soil and groundwater. Soil source zones have been identified at locations where the chemicals were produced, handled or used. Few effective options exist for treatments that can meet local and federal soil standards. Over the past 30 plus years, thermal remediation technologies have grown from experimental and innovative prospects to mature and accepted solutions deployed effectively at many sites. More than 600 thermal case studies have been summarized by Horst and colleagues<ref name="HorstEtAl2021">Horst, J., Munholland, J., Hegele, P., Klemmer, M., Gattenby, J., 2021. In Situ Thermal Remediation for Source Areas: Technology Advances and a Review of the Market From 1988–2020. Groundwater Monitoring & Remediation, 41(1), p. 17. [https://doi.org/10.1111/gwmr.12424 doi: 10.1111/gwmr.12424] [[Media: gwmr.12424.pdf | Open Access Manuscript]]</ref>. [[Thermal Conduction Heating (TCH)]] has been used for higher temperature applications such as removal of [[1,4-Dioxane]]. This article reports recent experience with TCH treatment of PFAS-impacted soil. |

| − | While | + | ==Target Temperature and Duration== |

| + | PFAS behave differently from most other organics subjected to TCH treatment. While the boiling points of individual PFAS fall in the range of 150-400°C, their chemical and physical behavior creates additional challenges. Some PFAS form ionic species in certain pH ranges and salts under other chemical conditions. This intricate behavior and our limited understanding of what this means for our ability to remove the PFAS from soils means that direct testing of thermal treatment options is warranted. Crownover and colleagues<ref name="CrownoverEtAl2019"/> subjected PFAS-laden soil to bench-scale heating to temperatures between 200 and 400°C which showed strong reductions of PFAS concentrations at 350°C and complete removal of many PFAS compounds at 400°C. The soil concentrations of targeted PFAS were reduced to nearly undetectable levels in this study. | ||

| − | + | ==Heating Method== | |

| + | For semi-volatile compounds such as dioxins, furans, poly-chlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and Poly-Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH), thermal conduction heating has evolved as the dominant thermal technology because it is capable of achieving soil temperatures higher than the boiling point of water, which are necessary for complete removal of these organic compounds. Temperatures between 200 and 500°C have been required to achieve the desired reduction in contaminant concentrations<ref name="StegemeierVinegar2001">Stegemeier, G.L., Vinegar, H.J., 2001. Thermal Conduction Heating for In-Situ Thermal Desorption of Soils. Ch. 4.6, pp. 1-37. In: Chang H. Oh (ed.), Hazardous and Radioactive Waste Treatment Technologies Handbook, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. ISBN 9780849395864 [[Media: StegemeierVinegar2001.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. TCH has become a popular technology for PFAS treatment because temperatures in the 400°C range are needed. | ||

| − | + | The energy source for TCH can be electricity (most commonly used), or fossil fuels (typically gas, diesel or fuel oil). Electrically powered TCH offers the largest flexibility for power input which also can be supplied by renewable and sustainable energy sources. | |

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ==Energy Usage== |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | During large precipitation events the rate of water deposition exceeds the rate of water infiltration, resulting in surface runoff (also called stormwater runoff). Surface characteristics including soil texture, presence of impermeable surfaces (natural and artificial), slope, and density and type of vegetation all influence the amount of surface runoff from a given land area. The use of passive systems such as retention ponds and biofiltration cells for treatment of surface runoff is well established for urban and roadway runoff. Treatment in those cases is typically achieved by directing runoff into and through a small constructed wetland, often at the outlet of a retention basin, or via filtration by directing runoff through a more highly engineered channel or vault containing the treatment materials. Filtration based technologies have proven to be effective for the removal of metals, organics, and suspended solids<ref>Sansalone, J.J., 1999. In-situ performance of a passive treatment system for metal source control. Water Science and Technology, 39(2), pp. 193-200. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0273-1223(99)00023-2 doi: 10.1016/S0273-1223(99)00023-2]</ref><ref>Deletic, A., Fletcher, T.D., 2006. Performance of grass filters used for stormwater treatment—A field and modelling study. Journal of Hydrology, 317(3-4), pp. 261-275. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2005.05.021 doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2005.05.021]</ref><ref>Grebel, J.E., Charbonnet, J.A., Sedlak, D.L., 2016. Oxidation of organic contaminants by manganese oxide geomedia for passive urban stormwater treatment systems. Water Research, 88, pp. 481-491. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2015.10.019 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.10.019]</ref><ref>Seelsaen, N., McLaughlan, R., Moore, S., Ball, J.E., Stuetz, R.M., 2006. Pollutant removal efficiency of alternative filtration media in stormwater treatment. Water Science and Technology, 54(6-7), pp. 299-305. [https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2006.617 doi: 10.2166/wst.2006.617]</ref>. | |

| − | + | ===Surface Runoff on Ranges=== | |

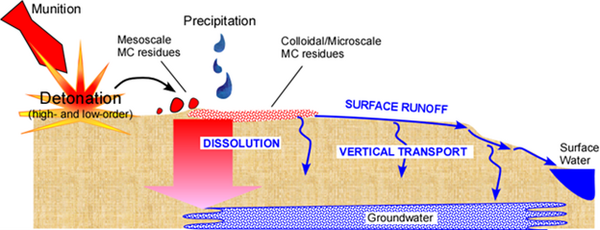

| + | [[File: FullerFig2.png | thumb | 600 px | Figure 2. Conceptual illustration of munition constituent production and transport on military ranges. Mesoscale residues are qualitatively defined as being easily visible to the naked eye (e.g., from around 50 µm to multiple cm in size) and less likely to be transported by moving water. Microscale residues are defined as <50 µm down to below 1 µm, and more likely to be entrained in, and transported by, moving water as particulates. Blue arrows represent possible water flow paths and include both dissolved and solid phase energetics. The red vertical arrow represents the predominant energetics dissolution process in close proximity to the residues due to precipitation.]] | ||

| + | Surface runoff represents a major potential mechanism through which energetics residues and related materials are transported off site from range soils to groundwater and surface water receptors (Figure 2). This process is particularly important for energetics that are water soluble (e.g., [[Wikipedia: Nitrotriazolone | NTO]] and [[Wikipedia: Nitroguanidine | NQ]]) or generate soluble daughter products (e.g., [[Wikipedia: 2,4-Dinitroanisole | DNAN]] and [[Wikipedia: TNT | TNT]]). While traditional MC such as [[Wikipedia: RDX | RDX]] and [[Wikipedia: HMX | HMX]] have limited aqueous solubility, they also exhibit recalcitrance to degrade under most natural conditions. RDX and [[Wikipedia: Perchlorate | perchlorate]] are frequent groundwater contaminants on military training ranges. While actual field measurements of energetics in surface runoff are limited, laboratory experiments have been performed to predict mobile energetics contamination levels based on soil mass loadings<ref>Cubello, F., Polyakov, V., Meding, S.M., Kadoya, W., Beal, S., Dontsova, K., 2024. Movement of TNT and RDX from composition B detonation residues in solution and sediment during runoff. Chemosphere, 350, Article 141023. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.141023 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.141023]</ref><ref>Karls, B., Meding, S.M., Li, L., Polyakov, V., Kadoya, W., Beal, S., Dontsova, K., 2023. A laboratory rill study of IMX-104 transport in overland flow. Chemosphere, 310, Article 136866. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136866 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136866] [[Media: KarlsEtAl2023.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref>Polyakov, V., Beal, S., Meding, S.M., Dontsova, K., 2025. Effect of gypsum on transport of IMX-104 constituents in overland flow under simulated rainfall. Journal of Environmental Quality, 54(1), pp. 191-203. [https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20652 doi: 10.1002/jeq2.20652] [[Media: PolyakovEtAl2025.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref><ref>Polyakov, V., Kadoya, W., Beal, S., Morehead, H., Hunt, E., Cubello, F., Meding, S.M., Dontsova, K., 2023. Transport of insensitive munitions constituents, NTO, DNAN, RDX, and HMX in runoff and sediment under simulated rainfall. Science of the Total Environment, 866, Article 161434. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161434 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161434] [[Media: PolyakovEtAl2023.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref><ref>Price, R.A., Bourne, M., Price, C.L., Lindsay, J., Cole, J., 2011. Transport of RDX and TNT from Composition-B Explosive During Simulated Rainfall. In: Environmental Chemistry of Explosives and Propellant Compounds in Soils and Marine Systems: Distributed Source Characterization and Remedial Technologies. American Chemical Society, pp. 229-240. [https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2011-1069.ch013 doi: 10.1021/bk-2011-1069.ch013]</ref>. For example, in a previous small study, MC were detected in surface runoff from an active live-fire range<ref>Fuller, M.E., 2015. Fate and Transport of Colloidal Energetic Residues. Department of Defense Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP), Project ER-1689. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/10760fd6-fb55-4515-a629-f93c555a92f0 Project Website] [[Media: ER-1689-FR.pdf | Final Report.pdf]]</ref>, and more recent sampling has detected MC in marsh surface water adjacent to the same installation (personal communication). Another recent report from Canada also detected RDX in both surface runoff and surface water at low part per billion levels in a survey of several military demolition sites<ref>Lapointe, M.-C., Martel, R., Diaz, E., 2017. A Conceptual Model of Fate and Transport Processes for RDX Deposited to Surface Soils of North American Active Demolition Sites. Journal of Environmental Quality, 46(6), pp. 1444-1454. [https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2017.02.0069 doi: 10.2134/jeq2017.02.0069]</ref>. However, overall, data regarding the MC contaminant profile of surface runoff from ranges is very limited, and the possible presence of non-energetic constituents (e.g., metals, binders, plasticizers) in runoff has not been examined. Additionally, while energetics-contaminated surface runoff is an important concern, mitigation technologies specifically for surface runoff have not yet been developed and widely deployed in the field. To effectively capture and degrade MC and associated compounds that are present in surface runoff, novel treatment media are needed to sorb a broad range of energetic materials and to transform the retained compounds through abiotic and/or microbial processes. | ||

| − | + | Surface runoff of organic and inorganic contaminants from live-fire ranges is a challenging issue for the Department of Defense (DoD). Potentially even more problematic is the fact that inputs to surface waters from large testing and training ranges typically originate from multiple sources, often encompassing hundreds of acres. No available technologies are currently considered effective for controlling non-point source energetics-laden surface runoff. While numerous technologies exist to treat collected explosives residues, contaminated soil and even groundwater, the decentralized nature and sheer volume of military range runoff have precluded the use of treatment technologies at full scale in the field. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Range Runoff Treatment Technology Components== | |

| − | + | Based on the conceptual foundation of previous research into surface water runoff treatment for other contaminants, with a goal to “trap and treat” the target compounds, the following components were selected for inclusion in the technology developed to address range runoff contaminated with energetic compounds. | |

| − | + | ===Peat=== | |

| + | Previous research demonstrated that a peat-based system provided a natural and sustainable sorptive medium for organic explosives such as HMX, RDX, and TNT, allowing much longer residence times than predicted from hydraulic loading alone<ref>Fuller, M.E., Hatzinger, P.B., Rungkamol, D., Schuster, R.L., Steffan, R.J., 2004. Enhancing the attenuation of explosives in surface soils at military facilities: Combined sorption and biodegradation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(2), pp. 313-324. [https://doi.org/10.1897/03-187 doi: 10.1897/03-187]</ref><ref>Fuller, M.E., Lowey, J.M., Schaefer, C.E., Steffan, R.J., 2005. A Peat Moss-Based Technology for Mitigating Residues of the Explosives TNT, RDX, and HMX in Soil. Soil and Sediment Contamination: An International Journal, 14(4), pp. 373-385. [https://doi.org/10.1080/15320380590954097 doi: 10.1080/15320380590954097]</ref><ref name="FullerEtAl2009">Fuller, M.E., Schaefer, C.E., Steffan, R.J., 2009. Evaluation of a peat moss plus soybean oil (PMSO) technology for reducing explosive residue transport to groundwater at military training ranges under field conditions. Chemosphere, 77(8), pp. 1076-1083. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.08.044 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.08.044]</ref><ref>Hatzinger, P.B., Fuller, M.E., Rungkamol, D., Schuster, R.L., Steffan, R.J., 2004. Enhancing the attenuation of explosives in surface soils at military facilities: Sorption-desorption isotherms. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(2), pp. 306-312. [https://doi.org/10.1897/03-186 doi: 10.1897/03-186]</ref><ref name="SchaeferEtAl2005">Schaefer, C.E., Fuller, M.E., Lowey, J.M., Steffan, R.J., 2005. Use of Peat Moss Amended with Soybean Oil for Mitigation of Dissolved Explosive Compounds Leaching into the Subsurface: Insight into Mass Transfer Mechanisms. Environmental Engineering Science, 22(3), pp. 337-349. [https://doi.org/10.1089/ees.2005.22.337 doi: 10.1089/ees.2005.22.337]</ref>. Peat moss represents a bioactive environment for treatment of the target contaminants. While the majority of the microbial reactions are aerobic due to the presence of measurable dissolved oxygen in the bulk solution, anaerobic reactions (including methanogenesis) can occur in microsites within the peat. The peat-based substrate acts not only as a long term electron donor as it degrades but also acts as a strong sorbent. This is important in intermittently loaded systems in which a large initial pulse of MC can be temporarily retarded on the peat matrix and then slowly degraded as they desorb<ref name="FullerEtAl2009"/><ref name="SchaeferEtAl2005"/>. This increased residence time enhances the biotransformation of energetics and promotes the immobilization and further degradation of breakdown products. Abiotic degradation reactions are also likely enhanced by association with the organic-rich peat (e.g., via electron shuttling reactions of [[Wikipedia: Humic substance | humics]])<ref>Roden, E.E., Kappler, A., Bauer, I., Jiang, J., Paul, A., Stoesser, R., Konishi, H., Xu, H., 2010. Extracellular electron transfer through microbial reduction of solid-phase humic substances. Nature Geoscience, 3, pp. 417-421. [https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo870 doi: 10.1038/ngeo870]</ref>. | ||

| − | + | ===Soybean Oil=== | |

| + | Modeling has indicated that peat moss amended with crude soybean oil would significantly reduce the flux of dissolved TNT, RDX, and HMX through the vadose zone to groundwater compared to a non-treated soil (see [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/20e2f05c-fd50-4fd3-8451-ba73300c7531 ESTCP ER-200434]). The technology was validated in field soil plots, showing a greater than 500-fold reduction in the flux of dissolved RDX from macroscale Composition B detonation residues compared to a non-treated control plot<ref name="FullerEtAl2009"/>. Laboratory testing and modeling indicated that the addition of soybean oil increased the biotransformation rates of RDX and HMX at least 10-fold compared to rates observed with peat moss alone<ref name="SchaeferEtAl2005"/>. Subsequent experiments also demonstrated the effectiveness of the amended peat moss material for stimulating perchlorate transformation when added to a highly contaminated soil (Fuller et al., unpublished data). These previous findings clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of peat-based materials for mitigating transport of both organic and inorganic energetic compounds through soil to groundwater. | ||

| − | + | ===Biochar=== | |

| + | Recent reports have highlighted additional materials that, either alone, or in combination with electron donors such as peat moss and soybean oil, may further enhance the sorption and degradation of surface runoff contaminants, including both legacy energetics and [[Wikipedia: Insensitive_munition#Insensitive_high_explosives | insensitive high explosives (IHE)]]. For instance, [[Wikipedia: Biochar | biochar]], a type of black carbon, has been shown to not only sorb a wide range of organic and inorganic contaminants including MCs<ref>Ahmad, M., Rajapaksha, A.U., Lim, J.E., Zhang, M., Bolan, N., Mohan, D., Vithanage, M., Lee, S.S., Ok, Y.S., 2014. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: A review. Chemosphere, 99, pp. 19-33. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.10.071 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.10.071]</ref><ref>Mohan, D., Sarswat, A., Ok, Y.S., Pittman, C.U., 2014. Organic and inorganic contaminants removal from water with biochar, a renewable, low cost and sustainable adsorbent – A critical review. Bioresource Technology, 160, pp. 191-202. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.01.120 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.01.120]</ref><ref>Oh, S.-Y., Seo, Y.-D., Jeong, T.-Y., Kim, S.-D., 2018. Sorption of Nitro Explosives to Polymer/Biomass-Derived Biochar. Journal of Environmental Quality, 47(2), pp. 353-360. [https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2017.09.0357 doi: 10.2134/jeq2017.09.0357]</ref><ref>Xie, T., Reddy, K.R., Wang, C., Yargicoglu, E., Spokas, K., 2015. Characteristics and Applications of Biochar for Environmental Remediation: A Review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 45(9), pp. 939-969. [https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2014.924180 doi: 10.1080/10643389.2014.924180]</ref>, but also to facilitate their degradation<ref>Oh, S.-Y., Cha, D.K., Kim, B.-J., Chiu, P.C., 2002. Effect of adsorption to elemental iron on the transformation of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene and hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine in solution. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 21(7), pp. 1384-1389. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620210708 doi: 10.1002/etc.5620210708]</ref><ref>Ye, J., Chiu, P.C., 2006. Transport of Atomic Hydrogen through Graphite and its Reaction with Azoaromatic Compounds. Environmental Science and Technology, 40(12), pp. 3959-3964. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es060038x doi: 10.1021/es060038x]</ref><ref name="OhChiu2009">Oh, S.-Y., Chiu, P.C., 2009. Graphite- and Soot-Mediated Reduction of 2,4-Dinitrotoluene and Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine. Environmental Science and Technology, 43(18), pp. 6983-6988. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es901433m doi: 10.1021/es901433m]</ref><ref name="OhEtAl2013">Oh, S.-Y., Son, J.-G., Chiu, P.C., 2013. Biochar-mediated reductive transformation of nitro herbicides and explosives. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 32(3), pp. 501-508. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.2087 doi: 10.1002/etc.2087] [[Media: OhEtAl2013.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref><ref name="XuEtAl2010">Xu, W., Dana, K.E., Mitch, W.A., 2010. Black Carbon-Mediated Destruction of Nitroglycerin and RDX by Hydrogen Sulfide. Environmental Science and Technology, 44(16), pp. 6409-6415. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es101307n doi: 10.1021/es101307n]</ref><ref>Xu, W., Pignatello, J.J., Mitch, W.A., 2013. Role of Black Carbon Electrical Conductivity in Mediating Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) Transformation on Carbon Surfaces by Sulfides. Environmental Science and Technology, 47(13), pp. 7129-7136. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es4012367 doi: 10.1021/es4012367]</ref>. Depending on the source biomass and [[Wikipedia: Pyrolysis| pyrolysis]] conditions, biochar can possess a high [[Wikipedia: Specific surface area | specific surface area]] (on the order of several hundred m<small><sup>2</sup></small>/g)<ref>Zhang, J., You, C., 2013. Water Holding Capacity and Absorption Properties of Wood Chars. Energy and Fuels, 27(5), pp. 2643-2648. [https://doi.org/10.1021/ef4000769 doi: 10.1021/ef4000769]</ref><ref>Gray, M., Johnson, M.G., Dragila, M.I., Kleber, M., 2014. Water uptake in biochars: The roles of porosity and hydrophobicity. Biomass and Bioenergy, 61, pp. 196-205. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2013.12.010 doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2013.12.010]</ref> and hence a high sorption capacity. Biochar and other black carbon also exhibit especially high affinity for [[Wikipedia: Nitro compound | nitroaromatic compounds (NACs)]] including TNT and 2,4-dinitrotoluene (DNT)<ref>Sander, M., Pignatello, J.J., 2005. Characterization of Charcoal Adsorption Sites for Aromatic Compounds: Insights Drawn from Single-Solute and Bi-Solute Competitive Experiments. Environmental Science and Technology, 39(6), pp. 1606-1615. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es049135l doi: 10.1021/es049135l]</ref><ref name="ZhuEtAl2005">Zhu, D., Kwon, S., Pignatello, J.J., 2005. Adsorption of Single-Ring Organic Compounds to Wood Charcoals Prepared Under Different Thermochemical Conditions. Environmental Science and Technology 39(11), pp. 3990-3998. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es050129e doi: 10.1021/es050129e]</ref><ref name="ZhuPignatello2005">Zhu, D., Pignatello, J.J., 2005. Characterization of Aromatic Compound Sorptive Interactions with Black Carbon (Charcoal) Assisted by Graphite as a Model. Environmental Science and Technology, 39(7), pp. 2033-2041. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es0491376 doi: 10.1021/es0491376]</ref>. This is due to the strong [[Wikipedia: Pi-interaction | ''π-π'' electron donor-acceptor interactions]] between electron-rich graphitic domains in black carbon and the electron-deficient aromatic ring of the NAC<ref name="ZhuEtAl2005"/><ref name="ZhuPignatello2005"/>. These characteristics make biochar a potentially effective, low cost, and sustainable sorbent for removing MC and other contaminants from surface runoff and retaining them for subsequent degradation ''in situ''. | ||

| − | + | Furthermore, black carbon such as biochar can promote abiotic and microbial transformation reactions by facilitating electron transfer. That is, biochar is not merely a passive sorbent for contaminants, but also a redox mediator for their degradation. Biochar can promote contaminant degradation through two different mechanisms: electron conduction and electron storage<ref>Sun, T., Levin, B.D.A., Guzman, J.J.L., Enders, A., Muller, D.A., Angenent, L.T., Lehmann, J., 2017. Rapid electron transfer by the carbon matrix in natural pyrogenic carbon. Nature Communications, 8, Article 14873. [https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14873 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14873] [[Media: SunEtAl2017.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref>. | |

| − | + | First, the microscopic graphitic regions in biochar can adsorb contaminants like NACs strongly, as noted above, and also conduct reducing equivalents such as electrons and atomic hydrogen to the sorbed contaminants, thus promoting their reductive degradation. This catalytic process has been demonstrated for TNT, DNT, RDX, HMX, and [[Wikipedia: Nitroglycerin | nitroglycerin]]<ref>Oh, S.-Y., Cha, D.K., Chiu, P.C., 2002. Graphite-Mediated Reduction of 2,4-Dinitrotoluene with Elemental Iron. Environmental Science and Technology, 36(10), pp. 2178-2184. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es011474g doi: 10.1021/es011474g]</ref><ref>Oh, S.-Y., Cha, D.K., Kim, B.J., Chiu, P.C., 2004. Reduction of Nitroglycerin with Elemental Iron: Pathway, Kinetics, and Mechanisms. Environmental Science and Technology, 38(13), pp. 3723-3730. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es0354667 doi: 10.1021/es0354667]</ref><ref>Oh, S.-Y., Cha, D.K., Kim, B.J., Chiu, P.C., 2005. Reductive transformation of hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine, octahydro-1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazocine, and methylenedinitramine with elemental iron. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 24(11), pp. 2812-2819. [https://doi.org/10.1897/04-662R.1 doi: 10.1897/04-662R.1]</ref><ref name="OhChiu2009"/><ref name="XuEtAl2010"/> and is expected to occur also for IHE including DNAN and NTO. | |

| − | + | Second, biochar contains in its structure abundant redox-facile functional groups such as [[Wikipedia: Quinone | quinones]] and [[Wikipedia: Hydroquinone | hydroquinones]], which are known to accept and donate electrons reversibly. Depending on the biomass and pyrolysis temperature, certain biochar can possess a rechargeable electron storage capacity (i.e., reversible electron accepting and donating capacity) on the order of several millimoles e<small><sup>–</sup></small>/g<ref>Klüpfel, L., Keiluweit, M., Kleber, M., Sander, M., 2014. Redox Properties of Plant Biomass-Derived Black Carbon (Biochar). Environmental Science and Technology, 48(10), pp. 5601-5611. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es500906d doi: 10.1021/es500906d]</ref><ref>Prévoteau, A., Ronsse, F., Cid, I., Boeckx, P., Rabaey, K., 2016. The electron donating capacity of biochar is dramatically underestimated. Scientific Reports, 6, Article 32870. [https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32870 doi: 10.1038/srep32870] [[Media: PrevoteauEtAl2016.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref><ref>Xin, D., Xian, M., Chiu, P.C., 2018. Chemical methods for determining the electron storage capacity of black carbon. MethodsX, 5, pp. 1515-1520. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2018.11.007 doi: 10.1016/j.mex.2018.11.007] [[Media: XinEtAl2018.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref>. This means that when "charged", biochar can provide electrons for either abiotic or biotic degradation of reducible compounds such as MC. The abiotic reduction of DNT and RDX mediated by biochar has been demonstrated<ref name="OhEtAl2013"/> and similar reactions are expected to occur for DNAN and NTO as well. Recent studies have shown that the electron storage capacity of biochar is also accessible to microbes. For example, soil bacteria such as [[Wikipedia: Geobacter | ''Geobacter'']] and [[Wikipedia: Shewanella | ''Shewanella'']] species can utilize oxidized (or "discharged") biochar as an electron acceptor for the oxidation of organic substrates such as lactate and acetate<ref>Kappler, A., Wuestner, M.L., Ruecker, A., Harter, J., Halama, M., Behrens, S., 2014. Biochar as an Electron Shuttle between Bacteria and Fe(III) Minerals. Environmental Science and Technology Letters, 1(8), pp. 339-344. [https://doi.org/10.1021/ez5002209 doi: 10.1021/ez5002209]</ref><ref name="SaquingEtAl2016">Saquing, J.M., Yu, Y.-H., Chiu, P.C., 2016. Wood-Derived Black Carbon (Biochar) as a Microbial Electron Donor and Acceptor. Environmental Science and Technology Letters, 3(2), pp. 62-66. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.5b00354 doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.5b00354]</ref> and reduced (or "charged") biochar as an electron donor for the reduction of nitrate<ref name="SaquingEtAl2016"/>. This is significant because, through microbial access of stored electrons in biochar, contaminants that do not sorb strongly to biochar can still be degraded. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Similar to nitrate, perchlorate and other relatively water-soluble energetic compounds (e.g., NTO and NQ) may also be similarly transformed using reduced biochar as an electron donor. Unlike other electron donors, biochar can be recharged through biodegradation of organic substrates<ref name="SaquingEtAl2016"/> and thus can serve as a long-lasting sorbent and electron repository in soil. Similar to peat moss, the high porosity and surface area of biochar not only facilitate contaminant sorption but also create anaerobic reducing microenvironments in its inner pores, where reductive degradation of energetic compounds can take place. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Other Sorbents=== | |

| + | Chitin and unmodified cellulose were predicted by [[Wikipedia: Density functional theory | Density Functional Theory]] methods to be favorable for absorption of NTO and NQ, as well as the legacy explosives<ref>Todde, G., Jha, S.K., Subramanian, G., Shukla, M.K., 2018. Adsorption of TNT, DNAN, NTO, FOX7, and NQ onto Cellulose, Chitin, and Cellulose Triacetate. Insights from Density Functional Theory Calculations. Surface Science, 668, pp. 54-60. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susc.2017.10.004 doi: 10.1016/j.susc.2017.10.004] [[Media: ToddeEtAl2018.pdf | Open Access Manuscript.pdf]]</ref>. Cationized cellulosic materials (e.g., cotton, wood shavings) have been shown to effectively remove negatively charged energetics like perchlorate and NTO from solution<ref name="FullerEtAl2022">Fuller, M.E., Farquharson, E.M., Hedman, P.C., Chiu, P., 2022. Removal of munition constituents in stormwater runoff: Screening of native and cationized cellulosic sorbents for removal of insensitive munition constituents NTO, DNAN, and NQ, and legacy munition constituents HMX, RDX, TNT, and perchlorate. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 424(C), Article 127335. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127335 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127335] [[Media: FullerEtAl2022.pdf | Open Access Manuscript.pdf]]</ref>. A substantial body of work has shown that modified cellulosic biopolymers can also be effective sorbents for removing metals from solution<ref>Burba, P., Willmer, P.G., 1983. Cellulose: a biopolymeric sorbent for heavy-metal traces in waters. Talanta, 30(5), pp. 381-383. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0039-9140(83)80087-3 doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(83)80087-3]</ref><ref>Brown, P.A., Gill, S.A., Allen, S.J., 2000. Metal removal from wastewater using peat. Water Research, 34(16), pp. 3907-3916. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00152-4 doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00152-4]</ref><ref>O’Connell, D.W., Birkinshaw, C., O’Dwyer, T.F., 2008. Heavy metal adsorbents prepared from the modification of cellulose: A review. Bioresource Technology, 99(15), pp. 6709-6724. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2008.01.036 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.01.036]</ref><ref>Wan Ngah, W.S., Hanafiah, M.A.K.M., 2008. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater by chemically modified plant wastes as adsorbents: A review. Bioresource Technology, 99(10), pp. 3935-3948. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2007.06.011 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.06.011]</ref> and therefore will also likely be applicable for some of the metals that may be found in surface runoff at firing ranges. | ||

| − | + | ==Technology Evaluation== | |

| + | Based on the properties of the target munition constituents, a combination of materials was expected to yield the best results to facilitate the sorption and subsequent biotic and abiotic degradation of the contaminants. | ||

| − | + | ===Sorbents=== | |

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin-right: 30px; margin-left: auto; float:left; text-align:center;" | ||

| + | |+Table 1. [[Wikipedia: Freundlich equation | Freundlich]] and [[Wikipedia: Langmuir adsorption model | Langmuir]] adsorption parameters for insensitive and legacy explosives | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! rowspan="2" | Compound | ||

| + | ! colspan="5" | Freundlich | ||

| + | ! colspan="5" | Langmuir | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! <small>Parameter</small> !! Peat !! <small>CAT</small> Pine !! <small>CAT</small> Burlap !! <small>CAT</small> Cotton !! <small>Parameter</small> !! Peat !! <small>CAT</small> Pine !! <small>CAT</small> Burlap !! <small>CAT</small> Cotton | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | colspan="12" style="background-color:white;" | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! rowspan="3" | HMX | ||

| + | ! ''K<sub>f</sub>'' | ||

| + | | 0.08 +/- 0.00 || -- || -- || -- | ||

| + | ! ''q<sub>m</sub>'' <small>(mg/g)</small> | ||

| + | | 0.29 +/- 0.04 || -- || -- || -- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! ''n'' | ||

| + | | 1.70 +/- 0.18 || -- || -- || -- | ||

| + | ! ''b'' <small>(L/mg)</small> | ||

| + | | 0.39 +/- 0.09 || -- || -- || -- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>'' | ||

| + | | 0.91 || -- || -- || -- | ||

| + | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>'' | ||

| + | | 0.93 || -- || -- || -- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | colspan="12" style="background-color:white;" | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! rowspan="3" | RDX | ||

| + | ! ''K<sub>f</sub>'' | ||

| + | | 0.11 +/- 0.02 || -- || -- || -- | ||

| + | ! ''q<sub>m</sub>'' <small>(mg/g)</small> | ||

| + | | 0.38 +/- 0.05 || -- || -- || -- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! ''n'' | ||

| + | | 2.75 +/- 0.63 || -- || -- || -- | ||

| + | ! ''b'' <small>(L/mg)</small> | ||

| + | | 0.23 +/- 0.08 || -- || -- || -- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>'' | ||

| + | | 0.69 || -- || -- || -- | ||

| + | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>'' | ||

| + | | 0.69 || -- || -- || -- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | colspan="12" style="background-color:white;" | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! rowspan="3" | TNT | ||

| + | ! ''K<sub>f</sub>'' | ||

| + | | 1.21 +/- 0.15 || 1.02 +/- 0.04 || 0.36 +/- 0.02 || -- | ||

| + | ! ''q<sub>m</sub>'' <small>(mg/g)</small> | ||

| + | | 3.63 +/- 0.18 || 1.26 +/- 0.06 || -- || -- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! ''n'' | ||

| + | | 2.78 +/- 0.67 || 4.01 +/- 0.44 || 1.59 +/- 0.09 || -- | ||

| + | ! ''b'' <small>(L/mg)</small> | ||

| + | | 0.89 +/- 0.13 || 0.76 +/- 0.10 || -- || -- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>'' | ||

| + | | 0.81 || 0.93 || 0.98 || -- | ||

| + | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>'' | ||

| + | | 0.97 || 0.97 || -- || -- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | colspan="12" style="background-color:white;" | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! rowspan="3" | NTO | ||

| + | ! ''K<sub>f</sub>'' | ||

| + | | -- || 0.94 +/- 0.05 || 0.41 +/- 0.05 || 0.26 +/- 0.06 | ||

| + | ! ''q<sub>m</sub>'' <small>(mg/g)</small> | ||

| + | | -- || 4.07 +/- 0.26 || 1.29 +/- 0.12 || 0.83 +/- .015 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! ''n'' | ||

| + | | -- || 1.61 +/- 0.11 || 2.43 +/- 0.41 || 2.53 +/- 0.76 | ||

| + | ! ''b'' <small>(L/mg)</small> | ||

| + | | -- || 0.30 +/- 0.04 || 0.36 +/- 0.08 || 0.30 +/- 0.15 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>'' | ||

| + | | -- || 0.97 || 0.82 || 0.57 | ||

| + | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>'' | ||

| + | | -- || 0.99 || 0.89 || 0.58 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | colspan="12" style="background-color:white;" | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! rowspan="3" | DNAN | ||

| + | ! ''K<sub>f</sub>'' | ||

| + | | 0.38 +/- 0.05 || 0.01 +/- 0.01 || -- || -- | ||

| + | ! ''q<sub>m</sub>'' <small>(mg/g)</small> | ||

| + | | 2.57 +/- 0.33 || -- || -- || -- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! ''n'' | ||

| + | | 1.71 +/- 0.20 || 0.70 +/- 0.13 || -- || -- | ||

| + | ! ''b'' <small>(L/mg)</small> | ||

| + | | 0.13 +/- 0.03 || -- || -- || -- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>'' | ||

| + | | 0.89 || 0.76 || -- || -- | ||

| + | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>'' | ||

| + | | 0.92 || -- || -- || -- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | colspan="12" style="background-color:white;" | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! rowspan="3" | ClO<sub>4</sup> | ||

| + | ! ''K<sub>f</sub>'' | ||

| + | | -- || 1.54 +/- 0.06 || 0.53 +/- 0.03 || -- | ||

| + | ! ''q<sub>m</sub>'' <small>(mg/g)</small> | ||

| + | | -- || 3.63 +/- 0.18 || 1.26 +/- 0.06 || -- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! ''n'' | ||

| + | | -- || 2.42 +/- 0.16 || 2.42 +/- 0.26 || -- | ||

| + | ! ''b'' <small>(L/mg)</small> | ||

| + | | -- || 0.89 +/- 0.13 || 0.76 +/- 0.10 || -- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>'' | ||

| + | | -- || 0.97 || 0.92 || -- | ||

| + | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>'' | ||

| + | | -- || 0.97 || 0.97 || -- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | colspan="12" style="text-align:left; background-color:white;" |<small>Notes:</small><br /><big>'''--'''</big> <small>Indicates the algorithm failed to converge on the model fitting parameters, therefore there was no successful model fit.<br />'''CAT''' Indicates cationized material.</small> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | + | The materials screened included [[Wikipedia: Sphagnum | ''Sphagnum'' peat moss]], primarily for sorption of HMX, RDX, TNT, and DNAN, as well as [[Wikipedia: Cationization of cotton | cationized cellulosics]] for removal of perchlorate and NTO. The cationized cellulosics that were examined included: pine sawdust, pine shavings, aspen shavings, cotton linters (fine, silky fibers which adhere to cotton seeds after ginning), [[Wikipedia: Chitin | chitin]], [[Wikipedia: Chitosan | chitosan]], burlap (landscaping grade), [[Wikipedia: Coir | coconut coir]], raw cotton, raw organic cotton, cleaned raw cotton, cotton fabric, and commercially cationized fabrics. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | As shown in Table 1<ref name="FullerEtAl2022"/>, batch sorption testing indicated that a combination of Sphagnum peat moss and cationized pine shavings provided good removal of both the neutral organic energetics (HMX, RDX, TNT, DNAN) as well as the negatively charged energetics (perchlorate, NTO). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Slow Release Carbon Sources=== | |

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin-right: 30px; margin-left: auto; float:left; text-align:center;" | ||

| + | |+Table 2. Slow-release Carbon Sources | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! Material !! Abbreviation !! Commercial Source !! Notes | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | polylactic acid || PLA6 || [https://www.goodfellow.com/usa?srsltid=AfmBOoqEiqIbrvWb1Hn1Bc090efBUUfg6V4N3Vrn6ytajHMJR-FG1Ez- Goodfellow] || high molecular weight thermoplastic polyester | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | polylactic acid || PLA80 || [https://www.goodfellow.com/usa?srsltid=AfmBOoqEiqIbrvWb1Hn1Bc090efBUUfg6V4N3Vrn6ytajHMJR-FG1Ez- Goodfellow] || low molecular weight thermoplastic polyester | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | polyhydroxybutyrate || PHB || [https://www.goodfellow.com/usa?srsltid=AfmBOoqEiqIbrvWb1Hn1Bc090efBUUfg6V4N3Vrn6ytajHMJR-FG1Ez- Goodfellow] || bacterial polyester | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | polycaprolactone || PCL || [https://www.sarchemlabs.com/?hsa_acc=4540346154&hsa_cam=20281343997&hsa_grp&hsa_ad&hsa_src=x&hsa_tgt&hsa_kw&hsa_mt&hsa_net=adwords&hsa_ver=3&gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=21209931835 Sarchem Labs] || biodegradable polyester | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | polybutylene succinate || BioPBS || [https://us.mitsubishi-chemical.com/company/performance-polymers/ Mitsubishi Chemical Performance Polymers] || compostable bio-based product | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | sucrose ester of fatty acids || SEFA SP10 || [https://www.sisterna.com/ Sisterna] || food and cosmetics additive | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | sucrose ester of fatty acids || SEFA SP70 || [https://www.sisterna.com/ Sisterna] || food and cosmetics additive | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | + | A range of biopolymers widely used in the production of biodegradable plastics were screened for their ability to support aerobic and anoxic biodegradation of the target munition constituents. These compounds and their sources are listed in Table 2. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File: FullerFig3.png | thumb | 400 px | Figure 3. Schematic of interactions between biochar and munitions constituents]] | |

| − | + | Multiple pure bacterial strains and mixed cultures were screened for their ability to utilize the solid biopolymers as a carbon source to support energetic compound transformation and degradation. Pure strains included the aerobic RDX degrader [[Wikipedia: Rhodococcus | ''Rhodococcus'']] species DN22 (DN22 henceforth)<ref name="ColemanEtAl1998">Coleman, N.V., Nelson, D.R., Duxbury, T., 1998. Aerobic biodegradation of hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) as a nitrogen source by a Rhodococcus sp., strain DN22. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 30(8-9), pp. 1159-1167. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-0717(97)00172-7 doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(97)00172-7]</ref> and [[Wikipedia: Gordonia (bacterium)|''Gordonia'']] species KTR9 (KTR9 henceforth)<ref name="ColemanEtAl1998"/>, the anoxic RDX degrader [[Wikipedia: Pseudomonas fluorencens | ''Pseudomonas fluorencens'']] species I-C (I-C henceforth)<ref>Pak, J.W., Knoke, K.L., Noguera, D.R., Fox, B.G., Chambliss, G.H., 2000. Transformation of 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene by Purified Xenobiotic Reductase B from Pseudomonas fluorescens I-C. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 66(11), pp. 4742-4750. [https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.66.11.4742-4750.2000 doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.11.4742-4750.2000] [[Media: PakEtAl2000.pdf | Open AccessArticle.pdf]]</ref><ref>Fuller, M.E., McClay, K., Hawari, J., Paquet, L., Malone, T.E., Fox, B.G., Steffan, R.J., 2009. Transformation of RDX and other energetic compounds by xenobiotic reductases XenA and XenB. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 84, pp. 535-544. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-009-2024-6 doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2024-6] [[Media: FullerEtAl2009.pdf | Open Access Manuscript]]</ref>, and the aerobic NQ degrader [[Wikipedia: Pseudomonas | ''Pseudomonas extremaustralis'']] species NQ5 (NQ5 henceforth)<ref>Kim, J., Fuller, M.E., Hatzinger, P.B., Chu, K.-H., 2024. Isolation and characterization of nitroguanidine-degrading microorganisms. Science of the Total Environment, 912, Article 169184. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169184 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169184]</ref>. Anaerobic mixed cultures were obtained from a membrane bioreactor (MBR) degrading a mixture of six explosives (HMX, RDX, TNT, NTO, NQ, DNAN), as well as perchlorate and nitrate<ref name="FullerEtAl2023">Fuller, M.E., Hedman, P.C., Chu, K.-H., Webster, T.S., Hatzinger, P.B., 2023. Evaluation of a sequential anaerobic-aerobic membrane bioreactor system for treatment of traditional and insensitive munitions constituents. Chemosphere, 340, Article 139887. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.139887 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.139887]</ref>. The results indicated that the slow-release carbon sources [[Wikipedia: Polyhydroxybutyrate | polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB)]], [[Wikipedia: Polycaprolactone | polycaprolactone (PCL)]], and [[Wikipedia: Polybutylene succinate | polybutylene succinate (BioPBS)]] were effective for supporting the biodegradation of the mixture of energetics. | |

| − | + | ===Biochar=== | |

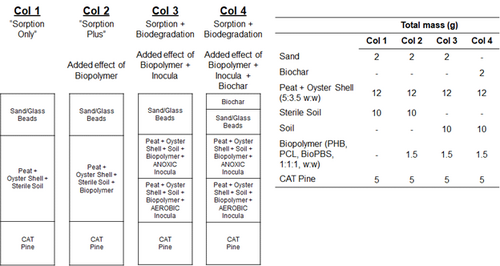

| − | + | [[File: FullerFig4.png | thumb | left | 500 px | Figure 4. Composition of the columns during the sorption-biodegradation experiments]] | |

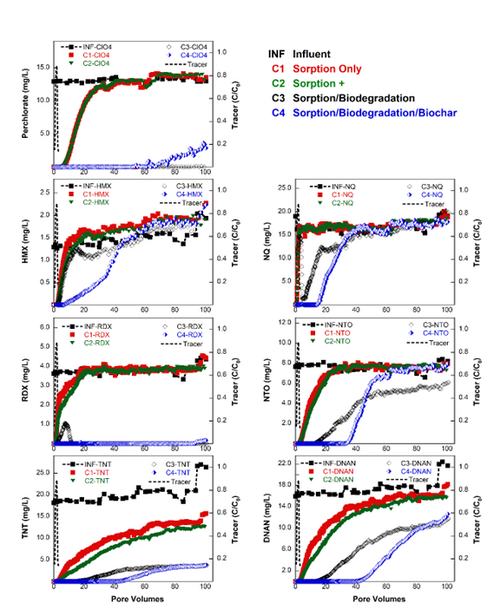

| + | [[File: FullerFig5.png | thumb | 500 px | Figure 5. Representative breakthrough curves of energetics during the second replication of the column sorption-biodegradation experiment]] | ||

| + | The ability of biochar to sorb and abiotically reduce legacy and insensitive munition constituents, as well as biochar’s use as an electron donor for microbial biodegradation of energetic compounds was examined. Batch experiments indicated that biochar was a reasonable sorbent for some of the energetics (RDX, DNAN), but could also serve as both an electron acceptor and an electron donor to facilitate abiotic (RDX, DNAN, NTO) and biotic (perchlorate) degradation (Figure 3)<ref>Xin, D., Giron, J., Fuller, M.E., Chiu, P.C., 2022. Abiotic reduction of 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO), DNAN, and RDX by wood-derived biochars through their rechargeable electron storage capacity. Environmental Science: Processes and Impacts, 24(2), pp. 316-329. [https://doi.org/10.1039/D1EM00447F doi: 10.1039/D1EM00447F] [[Media: XinEtAl2022.pdf | Open Access Manuscript.pdf]]</ref>. | ||

| − | + | ===Sorption-Biodegradation Column Experiments=== | |

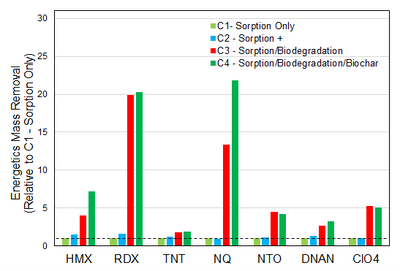

| + | The selected materials and cultures discussed above, along with a small amount of range soil and crushed oyster shell as a slow-release pH buffering agent, were packed into columns, and a steady flow of dissolved energetics was passed through the columns. The composition of the four columns is presented in Figure 4. The influent and effluent concentrations of the energetics was monitored over time. The column experiment was performed twice. As seen in Figure 5, there was sustained almost complete removal of RDX and ClO<sub>4</sub><sup>-</sup>, and more removal of the other energetics in the bioactive columns compared to the sorption only columns, over the course of the experiments. For reference, 100 PV is approximately equivalent to three months of operation. The higher effectiveness of sorption with biodegradation compared to sorption only is further illustrated in Figure 6, where the energetics mass removal in the bioactive columns was shown to be 2-fold (TNT) to 20-fold (RDX) higher relative to that observed in the sorption only column. The mass removal of HMX and NQ were both over 40% higher with biochar added to the sorption with biodegradation treatment, although biochar showed little added benefit for removal of other energetics tested. | ||

| − | == | + | ===Trap and Treat Technology=== |

| − | + | [[File: FullerFig6.png | thumb | left | 400 px | Figure 6. Energetic mass removal relative to the sorption only removal during the column sorption-biodegradation experiments. Dashed line given for reference to C1 removal = 1.]] | |

| + | These results provide a proof-of-concept for the further development of a passive and sustainable “trap-and-treat” technology for remediation of energetic compounds in stormwater runoff at military testing and training ranges. At a given site, the stormwater runoff would need to be fully characterized with respect to key parameters (e.g., pH, major anions), and site specific treatability testing would be recommended to assure there was nothing present in the runoff that would reduce performance. Effluent monitoring on a regular basis would also be needed (and would be likely be expected by state and local regulators) to assess performance decline over time. | ||

| − | + | The components of the technology would be predominantly peat moss and cationized pine shavings, supplemented with biochar, ground oyster shell, the biopolymer carbon sources, and the bioaugmentation cultures. The entire mix would likely be emplaced in a concrete vault at the outflow end of the stormwater runoff retention basin at the contaminated site. The deployed treatment system would have further design elements, such as a system to trap and retain suspended solids in the runoff in order to minimize clogging the matrix. the inside of the vault would be baffled to maximize the hydraulic retention time of the contaminated runoff. The biopolymer carbon sources and oyster shell may need be refreshed periodically (perhaps yearly) to maintain performance. However, a complete removal and replacement of the base media (peat moss, CAT pine) would not be advised, as that would lead to a loss of the acclimated biomass. | |

| − | == | + | ==Summary== |

| − | + | Novel sorbents and slow-release carbon sources can be an effective way to promote the sorption and biodegradation of a range of legacy and insensitive munition constituents from surface runoff, and the added benefits of biochar for both sorption and biotic and abiotic degradation of these compounds was demonstrated. These results establish a foundation for a passive, sustainable surface runoff treatment technology for both active and inactive military ranges. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

| − | + | *[https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/10760fd6-fb55-4515-a629-f93c555a92f0/er-1689-project-overview Fate and Transport of Colloidal Energetic Residues, SERDP Project ER-1689] | |

| − | * | + | *[https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/20e2f05c-fd50-4fd3-8451-ba73300c7531/er-200434-project-overview In Place Soil Treatments for Prevention of Explosives Contamination, ESTCP Project ER-200434] |

Latest revision as of 20:19, 4 November 2025

Thermal Conduction Heating for Treatment of PFAS-Impacted Soil

Removal of Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) compounds from impacted soils is challenging due to the modest volatility and varying properties of most PFAS compounds. Thermal treatment technologies have been developed for treatment of semi-volatile compounds in soils such as dioxins, furans, poly-aromatic hydrocarbons and poly-chlorinated biphenyls at temperatures near 325°C. In controlled bench-scale testing, complete removal of targeted PFAS compounds to concentrations below reporting limits of 0.5 µg/kg was demonstrated at temperatures of 400°C[1]. Three field-scale thermal PFAS treatment projects that have been completed in the US include an in-pile treatment demonstration, an in situ vadose zone treatment demonstration and a larger scale treatment demonstration with excavated PFAS-impacted soil in a constructed pile. Based on the results, thermal treatment temperatures of at least 400°C and a holding time of 7-10 days are recommended for reaching local and federal PFAS soil standards. The energy requirement to treat typical wet soil ranges from 300 to 400 kWh per cubic yard, exclusive of heat losses which are scale dependent. Extracted vapors have been treated using condensation and granular activated charcoal filtration, with thermal and catalytic oxidation as another option which is currently being evaluated for field scale applications. Compared to other options such as soil washing, the ability to treat on site and to treat all soil fractions is an advantage.

Related Article(s):

Contributors: Gorm Heron, Emily Crownover, Patrick Joyce, Ramona Iery

Key Resource:

- Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances thermal desorption evaluation[1]

Introduction

Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) have become prominent emerging contaminants in soil and groundwater. Soil source zones have been identified at locations where the chemicals were produced, handled or used. Few effective options exist for treatments that can meet local and federal soil standards. Over the past 30 plus years, thermal remediation technologies have grown from experimental and innovative prospects to mature and accepted solutions deployed effectively at many sites. More than 600 thermal case studies have been summarized by Horst and colleagues[2]. Thermal Conduction Heating (TCH) has been used for higher temperature applications such as removal of 1,4-Dioxane. This article reports recent experience with TCH treatment of PFAS-impacted soil.

Target Temperature and Duration

PFAS behave differently from most other organics subjected to TCH treatment. While the boiling points of individual PFAS fall in the range of 150-400°C, their chemical and physical behavior creates additional challenges. Some PFAS form ionic species in certain pH ranges and salts under other chemical conditions. This intricate behavior and our limited understanding of what this means for our ability to remove the PFAS from soils means that direct testing of thermal treatment options is warranted. Crownover and colleagues[1] subjected PFAS-laden soil to bench-scale heating to temperatures between 200 and 400°C which showed strong reductions of PFAS concentrations at 350°C and complete removal of many PFAS compounds at 400°C. The soil concentrations of targeted PFAS were reduced to nearly undetectable levels in this study.

Heating Method

For semi-volatile compounds such as dioxins, furans, poly-chlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and Poly-Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH), thermal conduction heating has evolved as the dominant thermal technology because it is capable of achieving soil temperatures higher than the boiling point of water, which are necessary for complete removal of these organic compounds. Temperatures between 200 and 500°C have been required to achieve the desired reduction in contaminant concentrations[3]. TCH has become a popular technology for PFAS treatment because temperatures in the 400°C range are needed.

The energy source for TCH can be electricity (most commonly used), or fossil fuels (typically gas, diesel or fuel oil). Electrically powered TCH offers the largest flexibility for power input which also can be supplied by renewable and sustainable energy sources.

Energy Usage

During large precipitation events the rate of water deposition exceeds the rate of water infiltration, resulting in surface runoff (also called stormwater runoff). Surface characteristics including soil texture, presence of impermeable surfaces (natural and artificial), slope, and density and type of vegetation all influence the amount of surface runoff from a given land area. The use of passive systems such as retention ponds and biofiltration cells for treatment of surface runoff is well established for urban and roadway runoff. Treatment in those cases is typically achieved by directing runoff into and through a small constructed wetland, often at the outlet of a retention basin, or via filtration by directing runoff through a more highly engineered channel or vault containing the treatment materials. Filtration based technologies have proven to be effective for the removal of metals, organics, and suspended solids[4][5][6][7].

Surface Runoff on Ranges

Surface runoff represents a major potential mechanism through which energetics residues and related materials are transported off site from range soils to groundwater and surface water receptors (Figure 2). This process is particularly important for energetics that are water soluble (e.g., NTO and NQ) or generate soluble daughter products (e.g., DNAN and TNT). While traditional MC such as RDX and HMX have limited aqueous solubility, they also exhibit recalcitrance to degrade under most natural conditions. RDX and perchlorate are frequent groundwater contaminants on military training ranges. While actual field measurements of energetics in surface runoff are limited, laboratory experiments have been performed to predict mobile energetics contamination levels based on soil mass loadings[8][9][10][11][12]. For example, in a previous small study, MC were detected in surface runoff from an active live-fire range[13], and more recent sampling has detected MC in marsh surface water adjacent to the same installation (personal communication). Another recent report from Canada also detected RDX in both surface runoff and surface water at low part per billion levels in a survey of several military demolition sites[14]. However, overall, data regarding the MC contaminant profile of surface runoff from ranges is very limited, and the possible presence of non-energetic constituents (e.g., metals, binders, plasticizers) in runoff has not been examined. Additionally, while energetics-contaminated surface runoff is an important concern, mitigation technologies specifically for surface runoff have not yet been developed and widely deployed in the field. To effectively capture and degrade MC and associated compounds that are present in surface runoff, novel treatment media are needed to sorb a broad range of energetic materials and to transform the retained compounds through abiotic and/or microbial processes.

Surface runoff of organic and inorganic contaminants from live-fire ranges is a challenging issue for the Department of Defense (DoD). Potentially even more problematic is the fact that inputs to surface waters from large testing and training ranges typically originate from multiple sources, often encompassing hundreds of acres. No available technologies are currently considered effective for controlling non-point source energetics-laden surface runoff. While numerous technologies exist to treat collected explosives residues, contaminated soil and even groundwater, the decentralized nature and sheer volume of military range runoff have precluded the use of treatment technologies at full scale in the field.

Range Runoff Treatment Technology Components

Based on the conceptual foundation of previous research into surface water runoff treatment for other contaminants, with a goal to “trap and treat” the target compounds, the following components were selected for inclusion in the technology developed to address range runoff contaminated with energetic compounds.

Peat

Previous research demonstrated that a peat-based system provided a natural and sustainable sorptive medium for organic explosives such as HMX, RDX, and TNT, allowing much longer residence times than predicted from hydraulic loading alone[15][16][17][18][19]. Peat moss represents a bioactive environment for treatment of the target contaminants. While the majority of the microbial reactions are aerobic due to the presence of measurable dissolved oxygen in the bulk solution, anaerobic reactions (including methanogenesis) can occur in microsites within the peat. The peat-based substrate acts not only as a long term electron donor as it degrades but also acts as a strong sorbent. This is important in intermittently loaded systems in which a large initial pulse of MC can be temporarily retarded on the peat matrix and then slowly degraded as they desorb[17][19]. This increased residence time enhances the biotransformation of energetics and promotes the immobilization and further degradation of breakdown products. Abiotic degradation reactions are also likely enhanced by association with the organic-rich peat (e.g., via electron shuttling reactions of humics)[20].

Soybean Oil

Modeling has indicated that peat moss amended with crude soybean oil would significantly reduce the flux of dissolved TNT, RDX, and HMX through the vadose zone to groundwater compared to a non-treated soil (see ESTCP ER-200434). The technology was validated in field soil plots, showing a greater than 500-fold reduction in the flux of dissolved RDX from macroscale Composition B detonation residues compared to a non-treated control plot[17]. Laboratory testing and modeling indicated that the addition of soybean oil increased the biotransformation rates of RDX and HMX at least 10-fold compared to rates observed with peat moss alone[19]. Subsequent experiments also demonstrated the effectiveness of the amended peat moss material for stimulating perchlorate transformation when added to a highly contaminated soil (Fuller et al., unpublished data). These previous findings clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of peat-based materials for mitigating transport of both organic and inorganic energetic compounds through soil to groundwater.

Biochar

Recent reports have highlighted additional materials that, either alone, or in combination with electron donors such as peat moss and soybean oil, may further enhance the sorption and degradation of surface runoff contaminants, including both legacy energetics and insensitive high explosives (IHE). For instance, biochar, a type of black carbon, has been shown to not only sorb a wide range of organic and inorganic contaminants including MCs[21][22][23][24], but also to facilitate their degradation[25][26][27][28][29][30]. Depending on the source biomass and pyrolysis conditions, biochar can possess a high specific surface area (on the order of several hundred m2/g)[31][32] and hence a high sorption capacity. Biochar and other black carbon also exhibit especially high affinity for nitroaromatic compounds (NACs) including TNT and 2,4-dinitrotoluene (DNT)[33][34][35]. This is due to the strong π-π electron donor-acceptor interactions between electron-rich graphitic domains in black carbon and the electron-deficient aromatic ring of the NAC[34][35]. These characteristics make biochar a potentially effective, low cost, and sustainable sorbent for removing MC and other contaminants from surface runoff and retaining them for subsequent degradation in situ.

Furthermore, black carbon such as biochar can promote abiotic and microbial transformation reactions by facilitating electron transfer. That is, biochar is not merely a passive sorbent for contaminants, but also a redox mediator for their degradation. Biochar can promote contaminant degradation through two different mechanisms: electron conduction and electron storage[36].

First, the microscopic graphitic regions in biochar can adsorb contaminants like NACs strongly, as noted above, and also conduct reducing equivalents such as electrons and atomic hydrogen to the sorbed contaminants, thus promoting their reductive degradation. This catalytic process has been demonstrated for TNT, DNT, RDX, HMX, and nitroglycerin[37][38][39][27][29] and is expected to occur also for IHE including DNAN and NTO.

Second, biochar contains in its structure abundant redox-facile functional groups such as quinones and hydroquinones, which are known to accept and donate electrons reversibly. Depending on the biomass and pyrolysis temperature, certain biochar can possess a rechargeable electron storage capacity (i.e., reversible electron accepting and donating capacity) on the order of several millimoles e–/g[40][41][42]. This means that when "charged", biochar can provide electrons for either abiotic or biotic degradation of reducible compounds such as MC. The abiotic reduction of DNT and RDX mediated by biochar has been demonstrated[28] and similar reactions are expected to occur for DNAN and NTO as well. Recent studies have shown that the electron storage capacity of biochar is also accessible to microbes. For example, soil bacteria such as Geobacter and Shewanella species can utilize oxidized (or "discharged") biochar as an electron acceptor for the oxidation of organic substrates such as lactate and acetate[43][44] and reduced (or "charged") biochar as an electron donor for the reduction of nitrate[44]. This is significant because, through microbial access of stored electrons in biochar, contaminants that do not sorb strongly to biochar can still be degraded.

Similar to nitrate, perchlorate and other relatively water-soluble energetic compounds (e.g., NTO and NQ) may also be similarly transformed using reduced biochar as an electron donor. Unlike other electron donors, biochar can be recharged through biodegradation of organic substrates[44] and thus can serve as a long-lasting sorbent and electron repository in soil. Similar to peat moss, the high porosity and surface area of biochar not only facilitate contaminant sorption but also create anaerobic reducing microenvironments in its inner pores, where reductive degradation of energetic compounds can take place.

Other Sorbents

Chitin and unmodified cellulose were predicted by Density Functional Theory methods to be favorable for absorption of NTO and NQ, as well as the legacy explosives[45]. Cationized cellulosic materials (e.g., cotton, wood shavings) have been shown to effectively remove negatively charged energetics like perchlorate and NTO from solution[46]. A substantial body of work has shown that modified cellulosic biopolymers can also be effective sorbents for removing metals from solution[47][48][49][50] and therefore will also likely be applicable for some of the metals that may be found in surface runoff at firing ranges.

Technology Evaluation

Based on the properties of the target munition constituents, a combination of materials was expected to yield the best results to facilitate the sorption and subsequent biotic and abiotic degradation of the contaminants.

Sorbents

| Compound | Freundlich | Langmuir | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Peat | CAT Pine | CAT Burlap | CAT Cotton | Parameter | Peat | CAT Pine | CAT Burlap | CAT Cotton | ||

| HMX | Kf | 0.08 +/- 0.00 | -- | -- | -- | qm (mg/g) | 0.29 +/- 0.04 | -- | -- | -- | |

| n | 1.70 +/- 0.18 | -- | -- | -- | b (L/mg) | 0.39 +/- 0.09 | -- | -- | -- | ||

| r2 | 0.91 | -- | -- | -- | r2 | 0.93 | -- | -- | -- | ||

| RDX | Kf | 0.11 +/- 0.02 | -- | -- | -- | qm (mg/g) | 0.38 +/- 0.05 | -- | -- | -- | |

| n | 2.75 +/- 0.63 | -- | -- | -- | b (L/mg) | 0.23 +/- 0.08 | -- | -- | -- | ||

| r2 | 0.69 | -- | -- | -- | r2 | 0.69 | -- | -- | -- | ||

| TNT | Kf | 1.21 +/- 0.15 | 1.02 +/- 0.04 | 0.36 +/- 0.02 | -- | qm (mg/g) | 3.63 +/- 0.18 | 1.26 +/- 0.06 | -- | -- | |

| n | 2.78 +/- 0.67 | 4.01 +/- 0.44 | 1.59 +/- 0.09 | -- | b (L/mg) | 0.89 +/- 0.13 | 0.76 +/- 0.10 | -- | -- | ||

| r2 | 0.81 | 0.93 | 0.98 | -- | r2 | 0.97 | 0.97 | -- | -- | ||

| NTO | Kf | -- | 0.94 +/- 0.05 | 0.41 +/- 0.05 | 0.26 +/- 0.06 | qm (mg/g) | -- | 4.07 +/- 0.26 | 1.29 +/- 0.12 | 0.83 +/- .015 | |

| n | -- | 1.61 +/- 0.11 | 2.43 +/- 0.41 | 2.53 +/- 0.76 | b (L/mg) | -- | 0.30 +/- 0.04 | 0.36 +/- 0.08 | 0.30 +/- 0.15 | ||

| r2 | -- | 0.97 | 0.82 | 0.57 | r2 | -- | 0.99 | 0.89 | 0.58 | ||

| DNAN | Kf | 0.38 +/- 0.05 | 0.01 +/- 0.01 | -- | -- | qm (mg/g) | 2.57 +/- 0.33 | -- | -- | -- | |

| n | 1.71 +/- 0.20 | 0.70 +/- 0.13 | -- | -- | b (L/mg) | 0.13 +/- 0.03 | -- | -- | -- | ||

| r2 | 0.89 | 0.76 | -- | -- | r2 | 0.92 | -- | -- | -- | ||

| ClO4 | Kf | -- | 1.54 +/- 0.06 | 0.53 +/- 0.03 | -- | qm (mg/g) | -- | 3.63 +/- 0.18 | 1.26 +/- 0.06 | -- | |

| n | -- | 2.42 +/- 0.16 | 2.42 +/- 0.26 | -- | b (L/mg) | -- | 0.89 +/- 0.13 | 0.76 +/- 0.10 | -- | ||

| r2 | -- | 0.97 | 0.92 | -- | r2 | -- | 0.97 | 0.97 | -- | ||

| Notes: -- Indicates the algorithm failed to converge on the model fitting parameters, therefore there was no successful model fit. CAT Indicates cationized material. | |||||||||||

The materials screened included Sphagnum peat moss, primarily for sorption of HMX, RDX, TNT, and DNAN, as well as cationized cellulosics for removal of perchlorate and NTO. The cationized cellulosics that were examined included: pine sawdust, pine shavings, aspen shavings, cotton linters (fine, silky fibers which adhere to cotton seeds after ginning), chitin, chitosan, burlap (landscaping grade), coconut coir, raw cotton, raw organic cotton, cleaned raw cotton, cotton fabric, and commercially cationized fabrics.

As shown in Table 1[46], batch sorption testing indicated that a combination of Sphagnum peat moss and cationized pine shavings provided good removal of both the neutral organic energetics (HMX, RDX, TNT, DNAN) as well as the negatively charged energetics (perchlorate, NTO).

Slow Release Carbon Sources

| Material | Abbreviation | Commercial Source | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| polylactic acid | PLA6 | Goodfellow | high molecular weight thermoplastic polyester |

| polylactic acid | PLA80 | Goodfellow | low molecular weight thermoplastic polyester |

| polyhydroxybutyrate | PHB | Goodfellow | bacterial polyester |

| polycaprolactone | PCL | Sarchem Labs | biodegradable polyester |

| polybutylene succinate | BioPBS | Mitsubishi Chemical Performance Polymers | compostable bio-based product |

| sucrose ester of fatty acids | SEFA SP10 | Sisterna | food and cosmetics additive |

| sucrose ester of fatty acids | SEFA SP70 | Sisterna | food and cosmetics additive |

A range of biopolymers widely used in the production of biodegradable plastics were screened for their ability to support aerobic and anoxic biodegradation of the target munition constituents. These compounds and their sources are listed in Table 2.

Multiple pure bacterial strains and mixed cultures were screened for their ability to utilize the solid biopolymers as a carbon source to support energetic compound transformation and degradation. Pure strains included the aerobic RDX degrader Rhodococcus species DN22 (DN22 henceforth)[51] and Gordonia species KTR9 (KTR9 henceforth)[51], the anoxic RDX degrader Pseudomonas fluorencens species I-C (I-C henceforth)[52][53], and the aerobic NQ degrader Pseudomonas extremaustralis species NQ5 (NQ5 henceforth)[54]. Anaerobic mixed cultures were obtained from a membrane bioreactor (MBR) degrading a mixture of six explosives (HMX, RDX, TNT, NTO, NQ, DNAN), as well as perchlorate and nitrate[55]. The results indicated that the slow-release carbon sources polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB), polycaprolactone (PCL), and polybutylene succinate (BioPBS) were effective for supporting the biodegradation of the mixture of energetics.

Biochar

The ability of biochar to sorb and abiotically reduce legacy and insensitive munition constituents, as well as biochar’s use as an electron donor for microbial biodegradation of energetic compounds was examined. Batch experiments indicated that biochar was a reasonable sorbent for some of the energetics (RDX, DNAN), but could also serve as both an electron acceptor and an electron donor to facilitate abiotic (RDX, DNAN, NTO) and biotic (perchlorate) degradation (Figure 3)[56].

Sorption-Biodegradation Column Experiments

The selected materials and cultures discussed above, along with a small amount of range soil and crushed oyster shell as a slow-release pH buffering agent, were packed into columns, and a steady flow of dissolved energetics was passed through the columns. The composition of the four columns is presented in Figure 4. The influent and effluent concentrations of the energetics was monitored over time. The column experiment was performed twice. As seen in Figure 5, there was sustained almost complete removal of RDX and ClO4-, and more removal of the other energetics in the bioactive columns compared to the sorption only columns, over the course of the experiments. For reference, 100 PV is approximately equivalent to three months of operation. The higher effectiveness of sorption with biodegradation compared to sorption only is further illustrated in Figure 6, where the energetics mass removal in the bioactive columns was shown to be 2-fold (TNT) to 20-fold (RDX) higher relative to that observed in the sorption only column. The mass removal of HMX and NQ were both over 40% higher with biochar added to the sorption with biodegradation treatment, although biochar showed little added benefit for removal of other energetics tested.

Trap and Treat Technology

These results provide a proof-of-concept for the further development of a passive and sustainable “trap-and-treat” technology for remediation of energetic compounds in stormwater runoff at military testing and training ranges. At a given site, the stormwater runoff would need to be fully characterized with respect to key parameters (e.g., pH, major anions), and site specific treatability testing would be recommended to assure there was nothing present in the runoff that would reduce performance. Effluent monitoring on a regular basis would also be needed (and would be likely be expected by state and local regulators) to assess performance decline over time.

The components of the technology would be predominantly peat moss and cationized pine shavings, supplemented with biochar, ground oyster shell, the biopolymer carbon sources, and the bioaugmentation cultures. The entire mix would likely be emplaced in a concrete vault at the outflow end of the stormwater runoff retention basin at the contaminated site. The deployed treatment system would have further design elements, such as a system to trap and retain suspended solids in the runoff in order to minimize clogging the matrix. the inside of the vault would be baffled to maximize the hydraulic retention time of the contaminated runoff. The biopolymer carbon sources and oyster shell may need be refreshed periodically (perhaps yearly) to maintain performance. However, a complete removal and replacement of the base media (peat moss, CAT pine) would not be advised, as that would lead to a loss of the acclimated biomass.

Summary

Novel sorbents and slow-release carbon sources can be an effective way to promote the sorption and biodegradation of a range of legacy and insensitive munition constituents from surface runoff, and the added benefits of biochar for both sorption and biotic and abiotic degradation of these compounds was demonstrated. These results establish a foundation for a passive, sustainable surface runoff treatment technology for both active and inactive military ranges.

References

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Crownover, E., Oberle, D., Heron, G., Kluger, M., 2019. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances thermal desorption evaluation. Remediation Journal, 29(4), pp. 77-81. doi: 10.1002/rem.21623

- ^ Horst, J., Munholland, J., Hegele, P., Klemmer, M., Gattenby, J., 2021. In Situ Thermal Remediation for Source Areas: Technology Advances and a Review of the Market From 1988–2020. Groundwater Monitoring & Remediation, 41(1), p. 17. doi: 10.1111/gwmr.12424 Open Access Manuscript

- ^ Stegemeier, G.L., Vinegar, H.J., 2001. Thermal Conduction Heating for In-Situ Thermal Desorption of Soils. Ch. 4.6, pp. 1-37. In: Chang H. Oh (ed.), Hazardous and Radioactive Waste Treatment Technologies Handbook, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. ISBN 9780849395864 Open Access Article

- ^ Sansalone, J.J., 1999. In-situ performance of a passive treatment system for metal source control. Water Science and Technology, 39(2), pp. 193-200. doi: 10.1016/S0273-1223(99)00023-2

- ^ Deletic, A., Fletcher, T.D., 2006. Performance of grass filters used for stormwater treatment—A field and modelling study. Journal of Hydrology, 317(3-4), pp. 261-275. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2005.05.021

- ^ Grebel, J.E., Charbonnet, J.A., Sedlak, D.L., 2016. Oxidation of organic contaminants by manganese oxide geomedia for passive urban stormwater treatment systems. Water Research, 88, pp. 481-491. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.10.019

- ^ Seelsaen, N., McLaughlan, R., Moore, S., Ball, J.E., Stuetz, R.M., 2006. Pollutant removal efficiency of alternative filtration media in stormwater treatment. Water Science and Technology, 54(6-7), pp. 299-305. doi: 10.2166/wst.2006.617

- ^ Cubello, F., Polyakov, V., Meding, S.M., Kadoya, W., Beal, S., Dontsova, K., 2024. Movement of TNT and RDX from composition B detonation residues in solution and sediment during runoff. Chemosphere, 350, Article 141023. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.141023

- ^ Karls, B., Meding, S.M., Li, L., Polyakov, V., Kadoya, W., Beal, S., Dontsova, K., 2023. A laboratory rill study of IMX-104 transport in overland flow. Chemosphere, 310, Article 136866. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136866 Open Access Article

- ^ Polyakov, V., Beal, S., Meding, S.M., Dontsova, K., 2025. Effect of gypsum on transport of IMX-104 constituents in overland flow under simulated rainfall. Journal of Environmental Quality, 54(1), pp. 191-203. doi: 10.1002/jeq2.20652 Open Access Article.pdf

- ^ Polyakov, V., Kadoya, W., Beal, S., Morehead, H., Hunt, E., Cubello, F., Meding, S.M., Dontsova, K., 2023. Transport of insensitive munitions constituents, NTO, DNAN, RDX, and HMX in runoff and sediment under simulated rainfall. Science of the Total Environment, 866, Article 161434. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161434 Open Access Article.pdf

- ^ Price, R.A., Bourne, M., Price, C.L., Lindsay, J., Cole, J., 2011. Transport of RDX and TNT from Composition-B Explosive During Simulated Rainfall. In: Environmental Chemistry of Explosives and Propellant Compounds in Soils and Marine Systems: Distributed Source Characterization and Remedial Technologies. American Chemical Society, pp. 229-240. doi: 10.1021/bk-2011-1069.ch013

- ^ Fuller, M.E., 2015. Fate and Transport of Colloidal Energetic Residues. Department of Defense Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP), Project ER-1689. Project Website Final Report.pdf