Difference between revisions of "User:Jhurley/sandbox"

(→Cap Design and Materials for Chemical Containment) |

(→Field Application) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | == | + | ==''In Situ'' Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE)== |

| − | + | The ''in situ'' Toxicity Identification Evaluation system is a tool to incorporate in weight-of-evidence studies at sites with numerous chemical toxicant classes present. The technology works by continuously sampling site water, immediately fractionating the water using diagnostic sorptive resins, and then exposing test organisms to the water to observe toxicity responses with minimal sample manipulation. It is compatible with various resins, test organisms, and common acute and chronic toxicity tests, and can be deployed at sites with a wide variety of physical and logistical considerations. | |

<div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | ||

'''Related Article(s):''' | '''Related Article(s):''' | ||

| + | |||

*[[Contaminated Sediments - Introduction]] | *[[Contaminated Sediments - Introduction]] | ||

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Contaminated Sediment Risk Assessment]] |

| − | |||

*[[Passive Sampling of Sediments]] | *[[Passive Sampling of Sediments]] | ||

| + | *[[Sediment Porewater Dialysis Passive Samplers for Inorganics (Peepers)]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Contributors:''' Dr. G. Allen Burton Jr., Austin Crane | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Key Resources:''' | ||

| + | *A Novel In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) System for Determining which Chemicals Drive Impairments at Contaminated Sites<ref name="BurtonEtAl2020">Burton, G.A., Cervi, E.C., Meyer, K., Steigmeyer, A., Verhamme, E., Daley, J., Hudson, M., Colvin, M., Rosen, G., 2020. A novel In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) System for Determining which Chemicals Drive Impairments at Contaminated Sites. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 39(9), pp. 1746-1754. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.4799 doi: 10.1002/etc.4799]</ref> | ||

| + | *An in situ toxicity identification and evaluation water analysis system: Laboratory validation<ref name="SteigmeyerEtAl2017">Steigmeyer, A.J., Zhang, J., Daley, J.M., Zhang, X., Burton, G.A. Jr., 2017. An in situ toxicity identification and evaluation water analysis system: Laboratory validation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 36(6), pp. 1636-1643. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.3696 doi: 10.1002/etc.3696]</ref> | ||

| + | *Sediment Toxicity Identification Evaluation (TIE) Phases I, II, and III Guidance Document<ref>United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2007. Sediment Toxicity Identification Evaluation (TIE) Phases I, II, and III Guidance Document, EPA/600/R-07/080. 145 pages. [https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPURL.cgi?Dockey=P1003GR1.txt Free Download] [[Media: EPA2007.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> | ||

| + | *In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) Technology for Assessing Contaminated Sediments, Remediation Success, Recontamination and Source Identification<ref>In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) Technology for Assessing Contaminated Sediments, Remediation Success, Recontamination and Source Identification [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/88a8f9ba-542b-4b98-bfa4-f693435535cd/er18-1181-project-overview Project Website] [[Media: ER18-1181Ph.II.pdf | Final Report.pdf]]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Introduction== | ||

| + | In waterways impacted by numerous naturally occurring and anthropogenic chemical stressors, it is crucial for environmental practitioners to be able to identify which chemical classes are causing the highest degrees of toxicity to aquatic life. Previously developed methods, including the Toxicity Identification Evaluation (TIE) protocol developed by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)<ref>Norberg-King, T., Mount, D.I., Amato, J.R., Jensen, D.A., Thompson, J.A., 1992. Toxicity identification evaluation: Characterization of chronically toxic effluents: Phase I. Publication No. EPA/600/6-91/005F. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development. [https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-09/documents/owm0255.pdf Free Download from US EPA] [[Media: usepa1992.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>, can be confounded by sample manipulation artifacts and temporal limitations of ''ex situ'' organism exposures<ref name="BurtonEtAl2020"/>. These factors may disrupt causal linkages and mislead investigators during site characterization and management decision-making. The ''in situ'' Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) technology was developed to allow users to strengthen stressor-causality linkages and rank chemical classes of concern at impaired sites, with high degrees of ecological realism. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The technology has undergone a series of improvements in recent years, with the most recent prototype being robust, operable in a wide variety of site conditions, and cost-effective compared to alternative site characterization methods<ref>Burton, G.A. Jr., Nordstrom, J.F., 2004. An in situ toxicity identification evaluation method part I: Laboratory validation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(12), pp. 2844-2850. [https://doi.org/10.1897/03-409.1 doi: 10.1897/03-409.1]</ref><ref>Burton, G.A. Jr., Nordstrom, J.F., 2004. An in situ toxicity identification evaluation method part II: Field validation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(12), pp. 2851-2855. [https://doi.org/10.1897/03-468.1 doi: 10.1897/03-468.1]</ref><ref name="BurtonEtAl2020"/><ref name="SteigmeyerEtAl2017"/>. The latest prototype can be used in any of the following settings: in marine, estuarine, or freshwater sites; to study surface water or sediment pore water; in shallow waters easily accessible by foot or in deep waters only accessible by pier or boat. It can be used to study sites impacted by a wide variety of stressors including ammonia, [[Metal and Metalloid Contaminants | metals]], pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB), [[Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) | polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH)]], and [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)]], among others. The technology is applicable to studies of acute toxicity via organism survival or of chronic toxicity via responses in growth, reproduction, or gene expression<ref name="BurtonEtAl2020"/>. | ||

| − | ''' | + | ==System Components and Validation== |

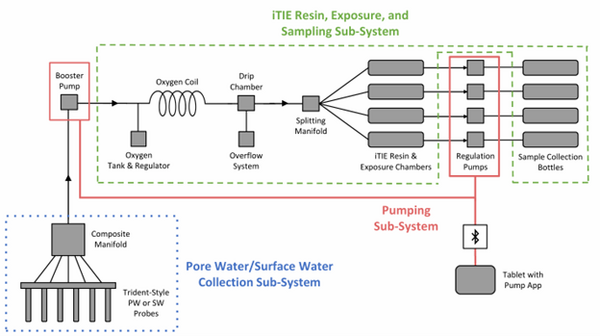

| − | + | [[File: CraneFig1.png | thumb | 600 px | Figure 1: A schematic diagram of the iTIE system prototype. The system is divided into three sub-systems: 1) the Pore Water/Surface Water Collection Sub-System (blue); 2) the Pumping Sub-System (red); and 3) the iTIE Resin, Exposure, and Sampling Sub-System (green). Water first enters the system through the Pore Water/Surface Water Collection Sub-System. Porewater can be collected using Trident-style probes, or surface water can be collected using a simple weighted probe. The water is composited in a manifold before being pumped to the rest of the iTIE system by the booster pump. Once in the iTIE Resin, Exposure, and Sampling Sub-System, the water is gently oxygenated by the Oxygen Coil, separated from gas bubbles by the Drip Chamber, and diverted to separate iTIE Resin and Exposure Chambers (or iTIE units) by the Splitting Manifold. Water movement through each iTIE unit is controlled by a dedicated Regulation Pump. Finally, the water is gathered in Sample Collection bottles for analysis.]] | |

| + | The latest iTIE prototype consists of an array of sorptive resins that differentially fractionate sampled water, and a series of corresponding flow-through organism chambers that receive the treated water ''in situ''. Resin treatments can be selected depending on the chemicals suspected to be present at each site to selectively sequester certain chemical of concern (CoC) classes from the whole water, leaving a smaller subset of chemicals in the resulting water fraction for chemical and toxicological characterization. Test organism species and life stages can also be chosen depending on factors including site characteristics and study goals. In the full iTIE protocol, site water is continuously sampled either from the sediment pore spaces or the water column at a site, gently oxygenated, diverted to different iTIE units for fractionation and organism exposure, and collected in sample bottles for off-site chemical analysis (Figure 1). All iTIE system components are housed within waterproof Pelican cases, which allow for ease of transport and temperature control. | ||

| − | + | ===Porewater and Surface Water Collection Sub-system=== | |

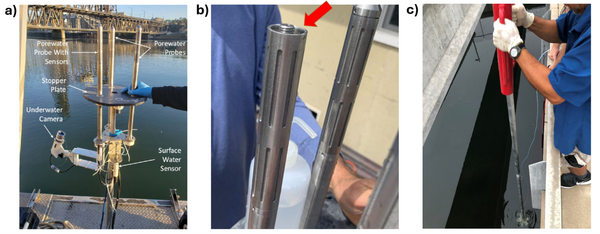

| − | + | [[File: CraneFig2.png | thumb | 600 px | Figure 2: a) Trident probe with auxiliary sensors attached, b) a Trident probe with end caps removed (the red arrow identifies the intermediate space where glass beads are packed to filter suspended solids), c) a Trident probe being installed using a series of push poles and a fence post driver]] | |

| + | Given the importance of sediment porewater to ecosystem structure and function, investigators may employ the iTIE system to evaluate the toxic effects associated with the impacted sediment porewater. To accomplish this, the iTIE system utilizes the Trident probe, originally developed for Department of Defense site characterization studies<ref>Chadwick, D.B., Harre, B., Smith, C.F., Groves, J.G., Paulsen, R.J., 2003. Coastal Contaminant Migration Monitoring: The Trident Probe and UltraSeep System. Hardware Description, Protocols, and Procedures. Technical Report 1902. Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center.</ref>. The main body of the Trident is comprised of a stainless-steel frame with six hollow probes (Figure 2). Each probe contains a layer of inert glass beads, which filters suspended solids from the sampled water. The water is drawn through each probe into a composite manifold and transported to the rest of the iTIE system using a high-precision peristaltic pump. | ||

| − | + | The Trident also includes an adjustable stopper plate, which forms a seal against the sediment and prevents the inadvertent dilution of porewater samples with surface water. (Figure 2). Preliminary laboratory results indicate that the Trident is extremely effective in collecting porewater samples with minimal surface water infiltration in sediments ranging from coarse sand to fine clay. Underwater cameras, sensors, passive samplers, and other auxiliary equipment can be attached to the Trident probe frame to provide supplemental data. | |

| − | == | + | Alternatively, practitioners may employ the iTIE system to evaluate site surface water. To sample surface water, weighted intake tubes can collect surface water from the water column using a peristaltic pump. |

| − | [[File: | + | |

| − | + | ===Oxygen Coil, Overflow Bag and Drip Chamber=== | |

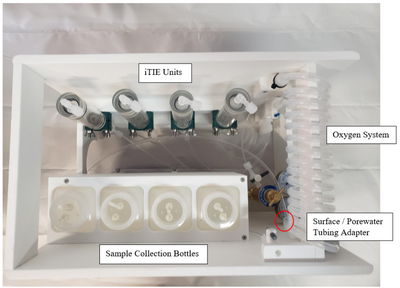

| + | [[File: CraneFig3.png | thumb | left | 400 px | Figure 3. Contents of the iTIE system cooler. The pictured HDPE rack (47.6 cm length x 29.7 cm width x 33.7 cm height) is removable from the iTIE cooler. Water enters the system at the red circle, flows through the oxygen coil, and then travels to each of the individual iTIE units where diagnostic resins and organisms are located. The water then briefly leaves the cooler to travel through peristaltic regulation pumps before being gathered in sample collection bottles.]] | ||

| + | Porewater is naturally anoxic due to limited mixing with aerated surface water and high oxygen demand of sediments, which may cause organism mortality and interfere with iTIE results. To preclude this, sampled porewater is exposed to an oxygen coil. This consists of an interior silicone tube connected to a pressurized oxygen canister, threaded through an exterior reinforced PVC tube through which water is slowly pumped (Figure 3). Pump rates are optimized to ensure adequate aeration of the water. In addition to elevating DO levels, the oxygen coil facilitates the oxidation of dissolved sulfides, which naturally occur in some marine sediments and may otherwise cause toxicity to organisms if left in its reduced form. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gas bubbles may form in the oxygen coil over the course of a deployment. These can be disruptive, decreasing water sample volumes and posing a danger to sensitive organisms like daphnids. To account for this, the water travels to a drip chamber after exiting the oxygen coil, which allows gas bubbles to be separated and diverted to an overflow system. The sample water then flows to a manifold which divides the flow into different paths to each of the treatment units for fractionation and organism exposure. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===iTIE Units: Fractionation and Organism Exposure Chambers=== | ||

| + | [[File: CraneFig4.png | thumb | 300px | Figure 4. A diagram of the iTIE prototype. Water flows upward into each resin chamber through the unit bottom. After being chemically fractionated in the resin chamber, water travels into the organism chamber, where test organisms have been placed. Water is drawn through the units by high-precision peristaltic pumps.]] | ||

| + | At the core of the iTIE system are separate dual-chamber iTIE units, each with a resin fractionation chamber and an organism exposure chamber (Figure 4). Developed by Burton ''et al.''<ref name="BurtonEtAl2020"/>, the iTIE prototype is constructed from acrylic, with rubber O-rings to connect each piece. Each iTIE unit can contain a different diagnostic resin matrix, customizable to remove specific chemical classes from the water. Sampled water flows into each unit through the bottom and is differentially fractionated by the resin matrix as it travels upward. Then it reaches the organism chamber, where test organisms are placed for exposure. The organism chamber inlet and outlet are covered by mesh to prevent the escape of the test organisms. This continuous flow-through design allows practitioners to capture the temporal heterogeneity of ambient water conditions over the duration of an ''in situ'' exposure. Currently, the iTIE system can support four independent iTIE treatment units. | ||

| − | + | After being exposed to test organisms, water is collected in sample bottles. The bottles can be pre-loaded with preservation reagents to allow for later chemical analysis. Sample bottles can be composed of polyethylene, glass or other materials depending on the CoC. | |

| − | The | + | ===Pumping Sub-system=== |

| + | [[File: CraneFig5.png | thumb | 300px | Figure 5. The iTIE system pumping sub-system. The sub-system consists of: A) a single booster pump, which is directly connected to the water sampling device and feeds water to the rest of the iTIE system, and B) a set of four regulation pumps, which each connect to the outflow of an individual iTIE unit. Each pump set is housed in a waterproof case with self-contained rechargeable battery power. A tablet is mounted inside the lid of the four pump case, which can be used to program and operate all of the pumps when connected to the internet.]] | ||

| + | Water movement through the system is driven by a series of high-precision, programmable peristaltic pumps ([https://ecotechmarine.com/ EcoTech Marine]). Each pump set is housed in a Pelican storm travel case. Power is supplied to each pump by internal rechargeable lithium-iron phosphate batteries ([https://www.bioennopower.com/ Bioenno Power]). | ||

| − | + | First, water is supplied to the system by a booster pump (Figure 5A). This pump is situated between the water sampling sub-system and the oxygen coil. The booster pump: 1) facilitates pore water collection, especially from sediments with high fine particle fractions; 2) helps water overcome vertical lifts to travel to the iTIE system; and 3) prevents vacuums from forming in the iTIE system interior, which can accelerate the formation of disruptive gas bubbles in the oxygen coil. The booster pump should be programmed to supply an excess of water to prevent vacuum formation. | |

| − | + | Second, a set of four regulation pumps ensure precise flow rates through each independent iTIE unit (Figure 5B). Each regulation pump pulls water from the top of an iTIE unit and then dispenses that water into a sample bottle for further analysis. | |

| − | + | ==Study Design Considerations== | |

| + | ===Diagnostic Resin Treatments=== | ||

| + | Several commercially available resins have been verified for use in the iTIE system. Investigators can select resins based on stressor classes of interest at each site. Each resin selectively removes a CoC class from site water prior to organism exposure. | ||

| + | *[https://www.dupont.com/products/ambersorb560.html DuPont Ambersorb 560] for removal of 1,4-dioxane and other organic chemicals<ref>Woodard, S., Mohr, T., Nickelsen, M.G., 2014. Synthetic media: A promising new treatment technology for 1,4-dioxane. Remediation Journal, 24(4), pp. 27-40. [https://doi.org/10.1002/rem.21402 doi: 10.1002/rem.21402]</ref> | ||

| + | *C18 for nonpolar organic chemicals | ||

| + | *[https://www.bio-rad.com/en-us Bio-Rad] [https://www.bio-rad.com/en-us/product/chelex-100-resin?ID=6448ab3e-b96a-4162-9124-7b7d2330288e Chelex] for metals | ||

| + | *Granular activated carbon for metals, general organic chemicals, sulfide<ref>Lemos, B.R.S., Teixeira, I.F., de Mesquita, J.P., Ribeiro, R.R., Donnici, C.L., Lago, R.M., 2012. Use of modified activated carbon for the oxidation of aqueous sulfide. Carbon, 50(3), pp. 1386-1393. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2011.11.011 doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2011.11.011]</ref> | ||

| + | *[https://www.waters.com/nextgen/us/en.html Waters] [https://www.waters.com/nextgen/us/en/search.html?category=Shop&isocode=en_US&keyword=oasis%20hlb&multiselect=true&page=1&rows=12&sort=best-sellers&xcid=ppc-ppc_23916&gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=14746094146&gbraid=0AAAAAD_uR00nhlNwrhhegNh06pBODTgiN&gclid=CjwKCAiAtLvMBhB_EiwA1u6_PsppE0raci2IhvGnAAe5ijciNcetLaGZo5qA3g3r4Z_La7YAPJtzShoC6LoQAvD_BwE Oasis HLB] for general organic chemicals<ref name="SteigmeyerEtAl2017"/> | ||

| + | *[https://www.waters.com/nextgen/us/en.html Waters] [https://www.waters.com/nextgen/us/en/search.html?category=All&enableHL=true&isocode=en_US&keyword=Oasis%20WAX%20&multiselect=true&page=1&rows=12&sort=most-relevant Oasis WAX] for PFAS, organic chemicals of mixed polarity<ref>Iannone, A., Carriera, F., Di Fiore, C., Avino, P., 2024. Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substance (PFAS) Analysis in Environmental Matrices: An Overview of the Extraction and Chromatographic Detection Methods. Analytica, 5(2), pp. 187-202. [https://doi.org/10.3390/analytica5020012 doi: 10.3390/analytica5020012] [[Media: IannoneEtAl2024.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> | ||

| + | *Zeolite for ammonia, other organic chemicals | ||

| − | + | Resins must be adequately conditioned prior to use. Otherwise, they may inadequately adsorb toxicants or cause stress to organisms. New resins should be tested for efficacy and toxicity before being used in an iTIE system. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Test Organism Species and Life Stages=== | |

| + | Practitioners can also select different organism species and life stages for use in the iTIE system, depending on site characteristics and study goals. The iTIE system can accommodate various small test organisms, including embryo-stage fish and most macroinvertebrates. The following common toxicity tests can be adapted for application within iTIE systems<ref>U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response, 1994. Catalogue of Standard Toxicity Tests for Ecological Risk Assessment. ECO Update, 2(2), 4 pages. Publication No. 9345.0.05I [https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-09/documents/v2no2.pdf Free Download] [[Media: usepa1994.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. | ||

| + | <ul><u>Freshwater acute toxicity:</u></ul> | ||

| + | *[[Wikipedia: Daphnia magna | ''Daphnia magna'']] or [[Wikipedia: Daphnia pulex | ''Daphnia pulex'']] 24-, 48-, and 96-hour survival | ||

| + | <ul><u>Freshwater chronic toxicity:</u></ul> | ||

| + | *[[Wikipedia: Ceriodaphnia dubia | ''Ceriodaphnia dubia'']] 7-day survival and reproduction | ||

| + | *''D. magna'' 7-day survival and reproduction | ||

| + | *[[Wikipedia: Fathead minnow | ''Pimephales promelas'']] 7-day embryo-larval survival and teratogenicity | ||

| + | *[[Wikipedia: Hyalella azteca | ''Hyalella Azteca'']] 10- or 30-day survival and reproduction | ||

| + | <ul><u>Marine acute toxicity:</u></ul> | ||

| + | *[[Wikipedia: Americamysis bahia | ''Americamysis bahia'']] 24- and 48-hour survival | ||

| + | <ul><u>Marine chronic toxicity:</u></ul> | ||

| + | *''Americamysis'' survival, growth and fecundity | ||

| + | *[[Wikipedia: Topsmelt silverside | ''Atherinops affinis'']] embryo-larval survival and growth | ||

| − | + | Acute toxicity is quantifiable via organism survival rates immediately following the termination of an iTIE system field deployment. Chronic toxicity can be quantified by continuing to culture and observe test organisms in-lab. Common chronic endpoints include stunted growth, altered development such as teratogenicity in larval fish, decreased reproduction rates, and changes in gene expression. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Several gene expression endpoints have been detectable in bioassays following an iTIE system deployment and in-lab culturing period. Steigmeyer ''et al.''<ref name="SteigmeyerEtAl2017"/> were able to detect changes in the expression of two genes in ''D. magna'' after a 24-hour exposure to bisphenol A. In a separate study, Nichols<ref>Nichols, E., 2023. Methods for Identification and Prioritization of Stressors at Impaired Sites. Masters thesis, University of Michigan. University of Michigan Library Deep Blue Documents. [https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/176142/Nichols_Elizabeth_thesis.pdf?sequence=1 Free Download] [[Media: Nichols2023.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> found a significant decline in acetylcholinesterase activity in ''H. azteca'' after a 24-hour exposure to chlorpyrifos. These results indicate a potential to adapt other gene expression bioassays for use in conjunction with iTIE system field exposures to prove stressor-causality linkages. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Cost Effectiveness Study=== | |

| + | Burton ''et al.''<ref name="BurtonEtAl2020"/> conducted a cost effectiveness study comparing the iTIE technology with the traditional US EPA Phase 1 TIE method. Comparisons were based on the estimated time required to complete various sub-tasks within each method. Sub-tasks included organism care, equipment preparation, mobilization and deployment, test maintenance, test termination, demobilization, and test termination analyses. It was ultimately estimated that the iTIE protocol requires 47% less time (67 fewer hours) to complete than the Phase 1 TIE method, with the largest time differences in equipment preparation, deployment, test maintenance, and demobilization. It is important to note that the iTIE method may require additional initial costs for equipment and training. | ||

| − | [[ | + | ==Field Application== |

| − | + | [[File: CraneFig6.png | thumb | left | 400px | Figure 6. iTIES deployment at the Rouge River, Detroit, MI. In the foreground is the iTIE Cooler Sub-System, which contains iTIE resin treatments and test organism groups, as well as the oxygenation coil and sample collection bottles. Next to the iTIE Cooler are the two pump cases. The Trident can be seen above the pump cases, installed in the river channel near shore.]] | |

| − | + | The iTIE system has been successfully deployed at a variety of marine and freshwater sites during the proof-of-concept phase of prototype development. One example is the 2024 iTIE system deployment completed near the mouth of the Rouge River in Detroit, MI (Figure 6). The Rouge River watershed has a long history of industrialization, with a legacy of chemical dumping, channelization, damming, and urban runoff<ref>Ridgway, J., Cave, K., DeMaria, A., O’Meara, J., Hartig, J. H., 2018. The Rouge River Area of Concern—A multi-year, multi-level successful approach to restoration of Impaired Beneficial Uses. Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management, 21(4), pp. 398-408. [https://doi.org/10.1080/14634988.2018.1528816 doi: 10.1080/14634988.2018.1528816]</ref>. This has led to degraded environmental conditions, with previous detections of a wide range of chemicals including heavy metals and various organics. | |

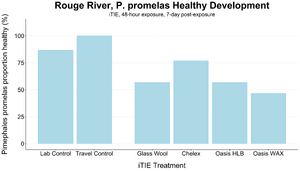

| − | + | [[File: CraneFig7.png | thumb | 300px | Figure 7. Survival and healthy development of ''P. promelas'' embryos and larvae following a 48-hour iTIE exposure near the mouth of the Rouge River. Organisms were exposed to site porewater as embryos for 48 hours and cultured post-exposure for an additional 5 days.]] | |

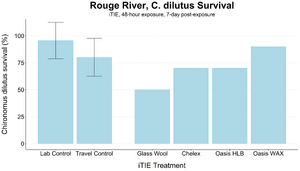

| + | [[File: CraneFig8.png | thumb | 300px | Figure 8. Survival of ''C. dilutus'' larvae after an iTIE exposure near the mouth of the Rouge River. Organisms were exposed to site porewater for 48 hours and cultured post-exposure for an additional 5 days. Error bars show standard deviation.]] | ||

| + | An iTIE system deployment was designed and completed to determine which chemical classes are most responsible for causing toxicity at the site. Resin treatments included glass wool (inert, non-fractionating substance), Chelex (metals sorption), Oasis HLB (general organics sorption), and Oasis WAX (organics sorption, with a high affinity for PFAS). The study utilized fathead minnow (''P. promelas'') embryos, due to their relative sensitivity to metals and PAHs, as well as second-instar midge ([[Wikipedia: Chironomus |''Chironomus dilutus'']]) larvae due to their relative sensitivity to PFAS. | ||

| − | + | The test organisms were exposed to fractionated porewater ''in situ'' for 48 hours. Following exposure, organisms were cultured for an additional five days, and survival was recorded (Figures 7 and 8). Moderate declines in survival were seen in both species in the glass wool treatment, indicating toxicity at the site. For ''P. promelas'', the highest proportion of healthy development occurred in the Chelex treatment, supporting the hypothesis that metals are a dominant cause of toxicity. ''C. dilutus'' had the greatest survival in the Oasis WAX treatment, suggesting that an organic stressor class like PFAS is also present at harmful concentrations in the river. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Water chemical analyses of fractionated and unfractionated water samples were completed to support biological results. Analyses were conducted for a range of stressor classes including metals, PAHs, PCBs, an organophosphate pesticide (chlorpyrifos), a PFAS compound (PFOS) and a pyrethroid insecticide (permethrin). Of these analytes, only heavy metals and PFOS were detected. Some chemical classes including PAHs and PCBs were not detected at the site. | |

| − | + | To reach similar conclusions using traditional Phase 1 TIE methods, one would need to complete the following tests: baseline toxicity, filtration, aeration, EDTA, C18 SPE, and methanol elution of C18 SPE. The iTIE method allows the same conclusions to be drawn with significantly less time and effort required. | |

==Summary== | ==Summary== | ||

| − | + | The ''in situ'' Toxicity Identification Evaluation technology and protocol is a powerful tool that investigators can use to strengthen causal linkages between chemical stressors and ecological toxicity. By fractionating sampled water and exposing test organisms ''in situ'', investigators can gather toxicity response data while minimizing sample manipulation and accurately representing environmental conditions. | |

| + | <br clear="right"/> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Latest revision as of 16:10, 3 March 2026

In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE)

The in situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation system is a tool to incorporate in weight-of-evidence studies at sites with numerous chemical toxicant classes present. The technology works by continuously sampling site water, immediately fractionating the water using diagnostic sorptive resins, and then exposing test organisms to the water to observe toxicity responses with minimal sample manipulation. It is compatible with various resins, test organisms, and common acute and chronic toxicity tests, and can be deployed at sites with a wide variety of physical and logistical considerations.

Related Article(s):

- Contaminated Sediments - Introduction

- Contaminated Sediment Risk Assessment

- Passive Sampling of Sediments

- Sediment Porewater Dialysis Passive Samplers for Inorganics (Peepers)

Contributors: Dr. G. Allen Burton Jr., Austin Crane

Key Resources:

- A Novel In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) System for Determining which Chemicals Drive Impairments at Contaminated Sites[1]

- An in situ toxicity identification and evaluation water analysis system: Laboratory validation[2]

- Sediment Toxicity Identification Evaluation (TIE) Phases I, II, and III Guidance Document[3]

- In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) Technology for Assessing Contaminated Sediments, Remediation Success, Recontamination and Source Identification[4]

Introduction

In waterways impacted by numerous naturally occurring and anthropogenic chemical stressors, it is crucial for environmental practitioners to be able to identify which chemical classes are causing the highest degrees of toxicity to aquatic life. Previously developed methods, including the Toxicity Identification Evaluation (TIE) protocol developed by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)[5], can be confounded by sample manipulation artifacts and temporal limitations of ex situ organism exposures[1]. These factors may disrupt causal linkages and mislead investigators during site characterization and management decision-making. The in situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) technology was developed to allow users to strengthen stressor-causality linkages and rank chemical classes of concern at impaired sites, with high degrees of ecological realism.

The technology has undergone a series of improvements in recent years, with the most recent prototype being robust, operable in a wide variety of site conditions, and cost-effective compared to alternative site characterization methods[6][7][1][2]. The latest prototype can be used in any of the following settings: in marine, estuarine, or freshwater sites; to study surface water or sediment pore water; in shallow waters easily accessible by foot or in deep waters only accessible by pier or boat. It can be used to study sites impacted by a wide variety of stressors including ammonia, metals, pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), among others. The technology is applicable to studies of acute toxicity via organism survival or of chronic toxicity via responses in growth, reproduction, or gene expression[1].

System Components and Validation

The latest iTIE prototype consists of an array of sorptive resins that differentially fractionate sampled water, and a series of corresponding flow-through organism chambers that receive the treated water in situ. Resin treatments can be selected depending on the chemicals suspected to be present at each site to selectively sequester certain chemical of concern (CoC) classes from the whole water, leaving a smaller subset of chemicals in the resulting water fraction for chemical and toxicological characterization. Test organism species and life stages can also be chosen depending on factors including site characteristics and study goals. In the full iTIE protocol, site water is continuously sampled either from the sediment pore spaces or the water column at a site, gently oxygenated, diverted to different iTIE units for fractionation and organism exposure, and collected in sample bottles for off-site chemical analysis (Figure 1). All iTIE system components are housed within waterproof Pelican cases, which allow for ease of transport and temperature control.

Porewater and Surface Water Collection Sub-system

Given the importance of sediment porewater to ecosystem structure and function, investigators may employ the iTIE system to evaluate the toxic effects associated with the impacted sediment porewater. To accomplish this, the iTIE system utilizes the Trident probe, originally developed for Department of Defense site characterization studies[8]. The main body of the Trident is comprised of a stainless-steel frame with six hollow probes (Figure 2). Each probe contains a layer of inert glass beads, which filters suspended solids from the sampled water. The water is drawn through each probe into a composite manifold and transported to the rest of the iTIE system using a high-precision peristaltic pump.

The Trident also includes an adjustable stopper plate, which forms a seal against the sediment and prevents the inadvertent dilution of porewater samples with surface water. (Figure 2). Preliminary laboratory results indicate that the Trident is extremely effective in collecting porewater samples with minimal surface water infiltration in sediments ranging from coarse sand to fine clay. Underwater cameras, sensors, passive samplers, and other auxiliary equipment can be attached to the Trident probe frame to provide supplemental data.

Alternatively, practitioners may employ the iTIE system to evaluate site surface water. To sample surface water, weighted intake tubes can collect surface water from the water column using a peristaltic pump.

Oxygen Coil, Overflow Bag and Drip Chamber

Porewater is naturally anoxic due to limited mixing with aerated surface water and high oxygen demand of sediments, which may cause organism mortality and interfere with iTIE results. To preclude this, sampled porewater is exposed to an oxygen coil. This consists of an interior silicone tube connected to a pressurized oxygen canister, threaded through an exterior reinforced PVC tube through which water is slowly pumped (Figure 3). Pump rates are optimized to ensure adequate aeration of the water. In addition to elevating DO levels, the oxygen coil facilitates the oxidation of dissolved sulfides, which naturally occur in some marine sediments and may otherwise cause toxicity to organisms if left in its reduced form.

Gas bubbles may form in the oxygen coil over the course of a deployment. These can be disruptive, decreasing water sample volumes and posing a danger to sensitive organisms like daphnids. To account for this, the water travels to a drip chamber after exiting the oxygen coil, which allows gas bubbles to be separated and diverted to an overflow system. The sample water then flows to a manifold which divides the flow into different paths to each of the treatment units for fractionation and organism exposure.

iTIE Units: Fractionation and Organism Exposure Chambers

At the core of the iTIE system are separate dual-chamber iTIE units, each with a resin fractionation chamber and an organism exposure chamber (Figure 4). Developed by Burton et al.[1], the iTIE prototype is constructed from acrylic, with rubber O-rings to connect each piece. Each iTIE unit can contain a different diagnostic resin matrix, customizable to remove specific chemical classes from the water. Sampled water flows into each unit through the bottom and is differentially fractionated by the resin matrix as it travels upward. Then it reaches the organism chamber, where test organisms are placed for exposure. The organism chamber inlet and outlet are covered by mesh to prevent the escape of the test organisms. This continuous flow-through design allows practitioners to capture the temporal heterogeneity of ambient water conditions over the duration of an in situ exposure. Currently, the iTIE system can support four independent iTIE treatment units.

After being exposed to test organisms, water is collected in sample bottles. The bottles can be pre-loaded with preservation reagents to allow for later chemical analysis. Sample bottles can be composed of polyethylene, glass or other materials depending on the CoC.

Pumping Sub-system

Water movement through the system is driven by a series of high-precision, programmable peristaltic pumps (EcoTech Marine). Each pump set is housed in a Pelican storm travel case. Power is supplied to each pump by internal rechargeable lithium-iron phosphate batteries (Bioenno Power).

First, water is supplied to the system by a booster pump (Figure 5A). This pump is situated between the water sampling sub-system and the oxygen coil. The booster pump: 1) facilitates pore water collection, especially from sediments with high fine particle fractions; 2) helps water overcome vertical lifts to travel to the iTIE system; and 3) prevents vacuums from forming in the iTIE system interior, which can accelerate the formation of disruptive gas bubbles in the oxygen coil. The booster pump should be programmed to supply an excess of water to prevent vacuum formation.

Second, a set of four regulation pumps ensure precise flow rates through each independent iTIE unit (Figure 5B). Each regulation pump pulls water from the top of an iTIE unit and then dispenses that water into a sample bottle for further analysis.

Study Design Considerations

Diagnostic Resin Treatments

Several commercially available resins have been verified for use in the iTIE system. Investigators can select resins based on stressor classes of interest at each site. Each resin selectively removes a CoC class from site water prior to organism exposure.

- DuPont Ambersorb 560 for removal of 1,4-dioxane and other organic chemicals[9]

- C18 for nonpolar organic chemicals

- Bio-Rad Chelex for metals

- Granular activated carbon for metals, general organic chemicals, sulfide[10]

- Waters Oasis HLB for general organic chemicals[2]

- Waters Oasis WAX for PFAS, organic chemicals of mixed polarity[11]

- Zeolite for ammonia, other organic chemicals

Resins must be adequately conditioned prior to use. Otherwise, they may inadequately adsorb toxicants or cause stress to organisms. New resins should be tested for efficacy and toxicity before being used in an iTIE system.

Test Organism Species and Life Stages

Practitioners can also select different organism species and life stages for use in the iTIE system, depending on site characteristics and study goals. The iTIE system can accommodate various small test organisms, including embryo-stage fish and most macroinvertebrates. The following common toxicity tests can be adapted for application within iTIE systems[12].

- Freshwater acute toxicity:

- Daphnia magna or Daphnia pulex 24-, 48-, and 96-hour survival

- Freshwater chronic toxicity:

- Ceriodaphnia dubia 7-day survival and reproduction

- D. magna 7-day survival and reproduction

- Pimephales promelas 7-day embryo-larval survival and teratogenicity

- Hyalella Azteca 10- or 30-day survival and reproduction

- Marine acute toxicity:

- Americamysis bahia 24- and 48-hour survival

- Marine chronic toxicity:

- Americamysis survival, growth and fecundity

- Atherinops affinis embryo-larval survival and growth

Acute toxicity is quantifiable via organism survival rates immediately following the termination of an iTIE system field deployment. Chronic toxicity can be quantified by continuing to culture and observe test organisms in-lab. Common chronic endpoints include stunted growth, altered development such as teratogenicity in larval fish, decreased reproduction rates, and changes in gene expression.

Several gene expression endpoints have been detectable in bioassays following an iTIE system deployment and in-lab culturing period. Steigmeyer et al.[2] were able to detect changes in the expression of two genes in D. magna after a 24-hour exposure to bisphenol A. In a separate study, Nichols[13] found a significant decline in acetylcholinesterase activity in H. azteca after a 24-hour exposure to chlorpyrifos. These results indicate a potential to adapt other gene expression bioassays for use in conjunction with iTIE system field exposures to prove stressor-causality linkages.

Cost Effectiveness Study

Burton et al.[1] conducted a cost effectiveness study comparing the iTIE technology with the traditional US EPA Phase 1 TIE method. Comparisons were based on the estimated time required to complete various sub-tasks within each method. Sub-tasks included organism care, equipment preparation, mobilization and deployment, test maintenance, test termination, demobilization, and test termination analyses. It was ultimately estimated that the iTIE protocol requires 47% less time (67 fewer hours) to complete than the Phase 1 TIE method, with the largest time differences in equipment preparation, deployment, test maintenance, and demobilization. It is important to note that the iTIE method may require additional initial costs for equipment and training.

Field Application

The iTIE system has been successfully deployed at a variety of marine and freshwater sites during the proof-of-concept phase of prototype development. One example is the 2024 iTIE system deployment completed near the mouth of the Rouge River in Detroit, MI (Figure 6). The Rouge River watershed has a long history of industrialization, with a legacy of chemical dumping, channelization, damming, and urban runoff[14]. This has led to degraded environmental conditions, with previous detections of a wide range of chemicals including heavy metals and various organics.

An iTIE system deployment was designed and completed to determine which chemical classes are most responsible for causing toxicity at the site. Resin treatments included glass wool (inert, non-fractionating substance), Chelex (metals sorption), Oasis HLB (general organics sorption), and Oasis WAX (organics sorption, with a high affinity for PFAS). The study utilized fathead minnow (P. promelas) embryos, due to their relative sensitivity to metals and PAHs, as well as second-instar midge (Chironomus dilutus) larvae due to their relative sensitivity to PFAS.

The test organisms were exposed to fractionated porewater in situ for 48 hours. Following exposure, organisms were cultured for an additional five days, and survival was recorded (Figures 7 and 8). Moderate declines in survival were seen in both species in the glass wool treatment, indicating toxicity at the site. For P. promelas, the highest proportion of healthy development occurred in the Chelex treatment, supporting the hypothesis that metals are a dominant cause of toxicity. C. dilutus had the greatest survival in the Oasis WAX treatment, suggesting that an organic stressor class like PFAS is also present at harmful concentrations in the river.

Water chemical analyses of fractionated and unfractionated water samples were completed to support biological results. Analyses were conducted for a range of stressor classes including metals, PAHs, PCBs, an organophosphate pesticide (chlorpyrifos), a PFAS compound (PFOS) and a pyrethroid insecticide (permethrin). Of these analytes, only heavy metals and PFOS were detected. Some chemical classes including PAHs and PCBs were not detected at the site. To reach similar conclusions using traditional Phase 1 TIE methods, one would need to complete the following tests: baseline toxicity, filtration, aeration, EDTA, C18 SPE, and methanol elution of C18 SPE. The iTIE method allows the same conclusions to be drawn with significantly less time and effort required.

Summary

The in situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation technology and protocol is a powerful tool that investigators can use to strengthen causal linkages between chemical stressors and ecological toxicity. By fractionating sampled water and exposing test organisms in situ, investigators can gather toxicity response data while minimizing sample manipulation and accurately representing environmental conditions.

References

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Burton, G.A., Cervi, E.C., Meyer, K., Steigmeyer, A., Verhamme, E., Daley, J., Hudson, M., Colvin, M., Rosen, G., 2020. A novel In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) System for Determining which Chemicals Drive Impairments at Contaminated Sites. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 39(9), pp. 1746-1754. doi: 10.1002/etc.4799

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Steigmeyer, A.J., Zhang, J., Daley, J.M., Zhang, X., Burton, G.A. Jr., 2017. An in situ toxicity identification and evaluation water analysis system: Laboratory validation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 36(6), pp. 1636-1643. doi: 10.1002/etc.3696

- ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2007. Sediment Toxicity Identification Evaluation (TIE) Phases I, II, and III Guidance Document, EPA/600/R-07/080. 145 pages. Free Download Report.pdf

- ^ In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) Technology for Assessing Contaminated Sediments, Remediation Success, Recontamination and Source Identification Project Website Final Report.pdf

- ^ Norberg-King, T., Mount, D.I., Amato, J.R., Jensen, D.A., Thompson, J.A., 1992. Toxicity identification evaluation: Characterization of chronically toxic effluents: Phase I. Publication No. EPA/600/6-91/005F. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development. Free Download from US EPA Report.pdf

- ^ Burton, G.A. Jr., Nordstrom, J.F., 2004. An in situ toxicity identification evaluation method part I: Laboratory validation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(12), pp. 2844-2850. doi: 10.1897/03-409.1

- ^ Burton, G.A. Jr., Nordstrom, J.F., 2004. An in situ toxicity identification evaluation method part II: Field validation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(12), pp. 2851-2855. doi: 10.1897/03-468.1

- ^ Chadwick, D.B., Harre, B., Smith, C.F., Groves, J.G., Paulsen, R.J., 2003. Coastal Contaminant Migration Monitoring: The Trident Probe and UltraSeep System. Hardware Description, Protocols, and Procedures. Technical Report 1902. Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center.

- ^ Woodard, S., Mohr, T., Nickelsen, M.G., 2014. Synthetic media: A promising new treatment technology for 1,4-dioxane. Remediation Journal, 24(4), pp. 27-40. doi: 10.1002/rem.21402

- ^ Lemos, B.R.S., Teixeira, I.F., de Mesquita, J.P., Ribeiro, R.R., Donnici, C.L., Lago, R.M., 2012. Use of modified activated carbon for the oxidation of aqueous sulfide. Carbon, 50(3), pp. 1386-1393. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2011.11.011

- ^ Iannone, A., Carriera, F., Di Fiore, C., Avino, P., 2024. Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substance (PFAS) Analysis in Environmental Matrices: An Overview of the Extraction and Chromatographic Detection Methods. Analytica, 5(2), pp. 187-202. doi: 10.3390/analytica5020012 Open Access Article

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response, 1994. Catalogue of Standard Toxicity Tests for Ecological Risk Assessment. ECO Update, 2(2), 4 pages. Publication No. 9345.0.05I Free Download Report.pdf

- ^ Nichols, E., 2023. Methods for Identification and Prioritization of Stressors at Impaired Sites. Masters thesis, University of Michigan. University of Michigan Library Deep Blue Documents. Free Download Report.pdf

- ^ Ridgway, J., Cave, K., DeMaria, A., O’Meara, J., Hartig, J. H., 2018. The Rouge River Area of Concern—A multi-year, multi-level successful approach to restoration of Impaired Beneficial Uses. Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management, 21(4), pp. 398-408. doi: 10.1080/14634988.2018.1528816