Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a class of man-made chemicals suspected to cause adverse human and ecological health effects. The acronym “PFAS” encompasses thousands of individual compounds. The two most studied and regulated are perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS). PFAS, including PFOA and PFOS, have entered the environment from a variety of sources and release scenarios, including releases from manufacturing facilities and areas where aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF), a type of fire-fighting foam, was applied. Many PFAS have unique physical and chemical properties that render them highly stable and resistant to degradation in the environment. They are typically removed from water supplies using granular activated carbon or ion exchange resins, although research is ongoing to develop in situ treatment technologies as well as more cost-effective ex situ treatment methods.

Related Article(s):

- PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment

- PFAS Soil Remediation Technologies

- PFAS Sources

- PFAS Transport and Fate

- PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma

- Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination - PFAS Destruction

- Soil & Groundwater Contaminants

- Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)

Contributor(s): Dr. Rula Deeb, Dr. Jennifer Field, Dr. Lydia Dorrance, Elisabeth Hawley and Dr. Christopher Higgins

Key Resource(s):

- U.S. EPA Emerging Contaminants - PFOS and PFOA Fact Sheet[1]

- Technical Fact Sheet: Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA)[2][2][2][2].

Introduction

PFAS were first developed in the 1940s and have been used by numerous industrial and commercial sectors for products that benefited from PFAS’ unique properties, including thermal and chemical stability, water resistance, stain resistance, and their surfactant nature. Awareness of PFAS in the environment first emerged in the late 1990s following developments in analytical instrumentation which enhanced detection of ionized substances such as PFAS[3]. This environmental awareness was generally concurrent to increased scrutiny into the health effects of PFAS[4]. In 2000, the sole U.S. manufacturer of PFOS voluntarily discontinued production[5]. Shortly thereafter, legal actions were taken against PFAS product manufacturing facilities in the Ohio River Valley in West Virginia[6]. Between 2006 and 2015, in cooperation with the EPA, eight global companies with PFAS-related operations voluntarily phased out the manufacture of PFOA and similarly structured PFAS with longer carbon chains[7]. In 2011, recognizing the potential impact of PFAS for the Department of Defense due to the military’s ubiquitous use of PFAS-containing AFFF, SERDP/ESTCP research programs began funding PFAS-related research, and the U.S. Air Force began conducting initial site investigations at former fire-fighting training areas[8]. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued provisional drinking water health advisories for PFOA and PFOS in 2009 and replaced these with more stringent health advisories in 2016[9]. Over the past five years, regulating agencies in several states have issued screening levels, notification levels, and health-based guidelines for PFOS, PFOA and other PFAS. Several states have undertaken statewide sampling programs of drinking water systems and groundwater resources in the vicinity of potential source areas including manufacturing facilities, military fire-training facilities, airports, refineries, and landfills[10][11].

Nomenclature

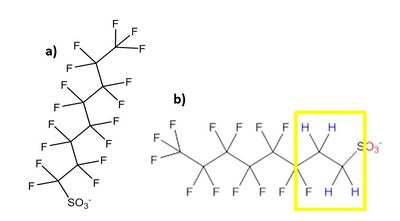

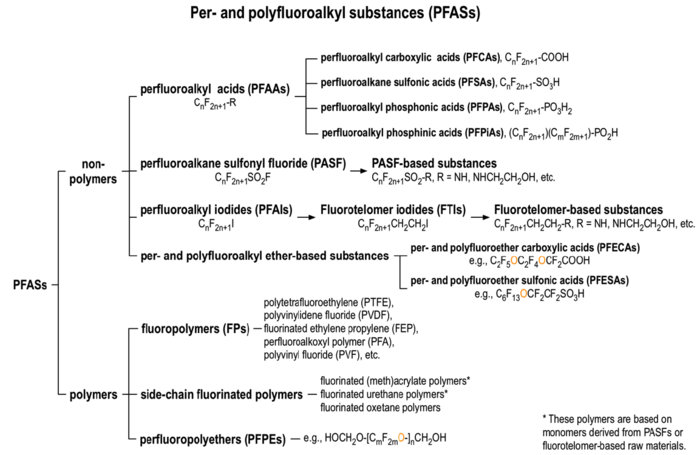

There are over 3,000 PFAS currently on the global market. A summary of families of compounds that are included in the umbrella terminology “PFAS” is provided in Figure 1[12]. Perfluoroalkyl compounds have a non-polar hydrophobic carbon (alkyl) chain structure that is fully saturated with fluorine atoms (i.e., they are perfluoroalkyl substances) attached to a hydrophilic polar functional group. Polyfluoroalkyl compounds have a similar structure but have at least one carbon that is bound to hydrogen rather than fluorine (Figure 2). Carbon chains may be linear or branched, leading to a variety of isomers. The term PFAS also includes fluoropolymers that may consist of thousands of shorter-chain units bonded together[13].

One of the most studied and regulated families of perfluoroalkyl compounds are the perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs), which include perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs) and perfluoroalkyl sulfonic acids (PFSAs). PFOA, a perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acid, and PFOS, a perfluoroalkyl sulfonic acid, are both PFAAs with eight carbons. Other PFCAs with the number of carbons ranging from nine to four include perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA), perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA), and perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA). PFAAs are sometimes differentiated as “long-chain” or “short-chain.” The term “long-chain” refers to PFCAs with eight or more carbons and PFSAs with six or more carbons. The term “short-chain” refers to PFCAs with seven or fewer carbons and PFSAs with five or fewer carbons[13].The PFAS naming conventions are explained in more detail in the video shown in Figure 3.

Physical and Chemical Properties

| Property | PFOS (Free Acid) | PFOA (Free Acid) |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Abstracts Service Number | 1763-23-1 | 335-67-1 |

| Physical State (at 25° C and 1 atmosphere pressure) | White powder | White powder/waxy white solid |

| Molecular weight (g/mol) | 500 | 414 |

| Water solubility at 25° C (mg/L) | 570a | 9,500a |

| Melting point (°C) | No data | 45 to 54 |

| Boiling point (°C) | 258 to 260 | 188 to 192 |

| Vapor pressure at 20° C (mm Hg) | 0.002 | 0.525 to 10 |

| Organic-carbon partition coefficient (log Koc) | 2.4 to 3.7 | 1.89 to 2.63 |

| Henry’s Law constant (atm-m3/mol) | Not measurable | 3.57x10-6 |

| Half-life | Atmospheric: 114 days Water: >41 years (at 25° C) Human: 3.1 to 7.4 years |

Atmospheric: 90 daysb Water: >92 years (at 25° C) Human: 2.1 to 8.5 years |

| Abbreviations: g/mol = grams per mole; mg/L = milligrams per liter; °C = degrees Celsius; mm Hg = millimeters of mercury; atm-m3/mol = atmosphere-cubic meters per mole | ||

| Notes: a Solubility in purified water. b The atmospheric half-life value for PFOA was extrapolated from available data measured over short study periods. | ||

The combination of the polar and non-polar structure makes PFAAs “amphiphilic,” associating with both water and oils, while the strength of their carbon-fluorine bonds lends them extremely high chemical and thermal stabilities. In most groundwater and surface water environments, PFAAs are found as the water-soluble anionic (i.e. deprotonated, negatively charged) form. Other groups of PFAS can be cationic (positively charged) or zwitterionic (possessing both a positive and negative charge) under typical environmental conditions. In general, documented physical properties of PFAS are scarce, and much that is available for PFAAs is related to the acid forms of the compounds, which are not typically found in the environment[13]. The surfactant properties of PFAAs complicate the prediction of their physiochemical properties, such as vapor pressure and partitioning coefficients. Some relevant properties of PFOS and PFOA are summarized in Table 1. A summary of the general characteristics of PFAS has been compiled in Table 6-2 of the ITRC fact sheet on PFAS naming conventions and physical and chemical properties[13].

Environmental Concern

Environmental concern surrounding PFAS stems from their widespread detection, high degree of environmental stability and mobility, and suspected toxicological effects on humans and the environment. Perfluorinated compounds, including PFAAs, are very stable and do not biodegrade. As a result, these compounds are found throughout the global environment. Trace amounts of perfluorinated compounds have been detected at remote locations like the Arctic, far from potential point sources[16]. Other studies have shown that some long-chain perfluorinated substances bioaccumulate and biomagnify in wildlife[17]. Because of this, higher trophic wildlife including fish and birds, and humans who consume them, can be particularly susceptible to any deleterious health effects posed by PFAS[18]. The Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment calculated a maximum permissible concentration for PFOS of 0.65 nanograms per liter (ng/L) for fresh water, based on human consumption of fish[1]. Recent fish and wildlife consumption advisories have been issued at certain locations in the United States associated with PFAS contamination[19][20].

Like other aspects of PFAS research, information on the toxicological effects of PFAS on humans is still emerging. PFOA and PFOS have half-lives of 2.1-8.5 years and 3.1-7.4 years, respectively, in humans[15]. PFAS typically accumulate in the liver, proteins, and the blood stream[2]. Toxicological and epidemiological studies of PFOA, PFOS and other PFAAs indicate potential association with a constellation of ailments including decreased fertility, increased cholesterol, suppression of response to vaccines, and certain cancers[15][21]. Both PFOA and PFOS are suspected carcinogens, but their carcinogenicity remains to be classified by the U.S. EPA[2]. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified PFOA as a Group 2B carcinogen, i.e., possibly carcinogenic to humans[22][23]. The U.S. EPA published draft oral reference doses of 20 ng/kg-day for both PFOA and PFOS (based on non-cancer hazard)[2]. Drinking water ingestion, fish consumption, dermal contact with water, and (accidental) ingestion of or contact with contaminated soil are the exposure pathways of concern with respect to human health.

Uses and Potential Sources to the Environment

Due to their unique properties, including surfactant qualities, heat and stain resistance, and amphiphilic nature, PFAS are used widely by a number of industries, including carpet, textile and leather production, chromium plating, photography, photolithography, paper products, semi-conductor manufacturing, coating additives, and cleaning products[24][25]. Sources to the environment include primary manufacturing facilities, where PFAS is produced, and secondary manufacturing facilities, where PFAS is incorporated into products. PFAS are found in a variety of consumer products including food paper and packaging, furnishings, waterproof clothing, and cosmetics[26]. The presence of PFAS in consumer products has created an urban background concentration in stormwater, wastewater treatment plant influent[27], and landfill leachate[28].

An additional widely documented source of PFAS is AFFF. AFFF is as a Class B firefighting foam used to combat flammable liquid fires. AFFF was released in large quantities at firefighting training areas as part of routine handling, fire-suppression training and equipment testing, and during fire emergency responses. While all AFFF contains PFAS[29], the types and concentrations of PFAS in AFFF vary among manufacturers and manufacturing time periods. 3M AFFF products were made using an electrochemical fluorination process that produced a high percentage of PFAS as PFOS, while other formulations were made using a telomerization process and contain a different suite of PFAS.

Regulation

The U.S. EPA recently developed Drinking Water Health Advisory levels for PFOA and PFOS, replacing previously published provisional values[9]. However, no Federal enforceable drinking water standards have been set. Recent years have seen increased regulatory activity at the state level, with around 20 states having guidance or advisory levels for one or more PFAS compounds in various environmental media (drinking water, groundwater, etc.). New Jersey is the first state to have promulgated an enforceable maximum concentration level (MCL) for a PFAS by setting an MCL for PFNA in 2018. Several other states, particularly in the eastern United States, are moving towards setting MCLs for various PFAS. Regulatory levels set or proposed by states vary but the majority are equivalent to or lower than the Federal Health Advisory level of 70 parts per trillion (ppt) combined concentration of PFOA and PFOS. The regulatory landscape for PFAS is developing rapidly. A regularly updated repository of regulatory levels is maintained by the ITRC (Figure 4).

Other regulatory actions have restricted the use and production of PFAS. PFOS was added to list of chemicals under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants in 2009. Nearly all use of PFOS is therefore banned in Europe, with some exemptions. Substances or mixtures may not contain PFOS above 0.001% by weight (EU 757/2010). In the U.S., because PFOS manufacturing was voluntarily phased out in 2002, AFFF containing PFOS is no longer manufactured. The U.S. military and others still have large quantities of stockpiled AFFF containing PFOS, although its use is discouraged[30][31].

Litigation

There have been many lawsuits filed with PFAS-related claims; some resulting in settlements in the hundreds of millions of dollars. In 2017 DuPont and Chemours paid nearly $700 million to settle 3,550 individual lawsuits claiming personal injury as a result of PFOA releases from DuPont’s former Washington Works manufacturing facility in Parkersburg, West Virginia. This settlement was reached after three of the lawsuits went to trial resulting in nearly $20 million in jury awards to the plaintiffs[32]. In 2018, 3M agreed to pay $850 million to settle a $5 billion natural resource damages claim related to PFAS impacts brought by Minnesota’s Attorney General[33]. In early 2019, numerous product liability lawsuits against former manufacturers of PFOS and PFOA and manufacturers of AFFF were consolidated into a multi-district litigation (MDL) pending before the U.S District Court of South Carolina[34]. Numerous additional PFAS-related lawsuits have been brought under common law tort, personal injury, product liability and natural resource protection laws across the United States. The proposed designation of PFAS as a hazardous substance under CERCLA[35] may have additional legal implications.

Sampling and Analytical Methods

Because of the presence of PFAS in many common consumer items and sampling materials, and the low reporting levels needed to compare to current regulatory guidelines, sampling for PFAS requires extra care to avoid cross contamination from other potential sources of PFAS. Most standard operating procedures and work plans advise avoiding the use of fluoropolymer-based (e.g., Teflon) components and recommend additional precautions related to sample containers, sampler clothing and handling of certain every-day items.

Commercial laboratories analyze PFAS in drinking water samples using the EPA-approved method 537.1, which consists of solid phase extraction and liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry[36]. Samples collected from any environmental media other than drinking water require a modified version of 537.1 to quantify approximately 24 individual PFAS compounds. An EPA method for some of these other media, Method 8327, was released for public comment in summer 2019[37]. Some commercial laboratories can extend the target analyte list to include up to 40 compounds. Some commercial laboratories also offer an analytical method known as the Total Oxidizable Precursor (TOP) assay, which provides a bulk measurement of PFAS mass in a sample, including that of oxidizable precursors[38][39]. Other approaches to quantify the total amount of organic fluorine in water samples include particle induced gamma-ray emission (PIGE) and absorbable organic fluorine (AOF)[26].

Fate and Transport

The processes of sorption and biotransformation as well as the presence of co-contaminants can affect the fate and transport of PFAS. It has been observed that PFAAs exhibit affinity for solid-phase organic carbon to varying degrees depending in part on chain length and structure, with long-chain compounds exhibiting a stronger affinity than short-chain and PFSAs exhibiting a stronger affinity than PFCAs for a given chain length[40]. Interactions with mineral phases, particularly ferric oxide materials, may also be important under certain conditions[41][42]. At present, empirical site-specific sorption estimates are recommended to accurately predict PFAS mobility[41]. PFAAs do not readily degrade in the environment. However, polyfluorinated forms may biotically or abiotically degrade to other intermediate forms and/or so-called “terminal,” recalcitrant PFAA forms, including PFOA and PFOS[43][44][45]. As a result, these degradable PFAS are sometimes referred as PFAA “precursors.” Remediation of co-contaminants, particularly using techniques involving oxidation, can enhance the degradation of precursors. Interactions between PFAS and non-aqueous phase liquids can retard PFAS migration[46]

Remediation Technologies

Due to the chemical and thermal stability of PFAS and the complexity of PFAS mixtures, soil and groundwater remediation is challenging and costly. Research is still ongoing to develop effective remedial strategies. Treatment options for soil include 1) treatment and/or direct on-site reuse, 2) temporary on-site storage, and 3) off-site disposal to a soil processing or treatment facility, licensed landfill, or incinerator. For groundwater, management options include the following: 1) in situ treatment, 2) ex situ treatment and/or reuse, aquifer reinjection, or discharge to surface water, stormwater, or sewer, 3) temporary on-site storage, and 4) off-site disposal to a hazardous waste treatment and disposal facility. The most common remediation approach is to use pump-and-treat with granular activated carbon followed by off-site incineration of the spent activated carbon. This technology has been used for years at full scale[47]. However, granular activated carbon has a relatively low capacity for PFAS particularly when shorter-chain compounds are present. Sorption capacity improvement tests have been conducted on various forms of granular and powdered activated carbon, ion exchange resins, and other sorbent materials as well as mixtures of clay, powdered activated carbon, and other sorbents[48]. Other methods for ex situ PFAS removal include high-pressure membrane treatment using nanofiltration or reverse osmosis[47][49][50]. Research into other PFAS treatment technologies, including in situ barriers (sequestration), biological treatment[51], advanced oxidation processes and in situ chemical reduction is ongoing.

Summary

PFAS are ubiquitous in a variety of industrial and commercial products, have been detected in many environmental media, pose potential risks to human and environmental health, and present challenges with respect to remediation. They are highly stable and mobile in the environment, may bioaccumulate and biomagnify in wildlife, and are the subject of litigation and regulatory actions at the local, state and Federal level. Health-based drinking water advisory levels are low, i.e., ng/L concentrations. As awareness of PFAS grows and regulatory criteria progress, site managers are conducting site investigations, improving analytical techniques, and designing and operating remediation systems. Current research, including that funded by SERDP/ESTCP, aims to demonstrate effective treatment technologies for PFAS and improve technology cost-effectiveness.

References

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2014. Emerging Contaminants Fact Sheet – Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA). EPA 505-F-14-001. March Fact Sheet

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2017. Technical Fact Sheet: Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA). EPA 505-F-17-001.

- ^ Hansen, K.J., L.A. Clemen, M.E. Ellefson and H.O. Johnson, 2001. Compound-Specific, Quantitative Characterization of Organic Fluorochemicals in Biological Matrices. Environmental Science and Technology 35(4):766-770.

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2018. Risk Management for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) under TSCA. https://www.epa.gov/assessing-and-managing-chemicals-under-tsca/risk-management-and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfass

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2000. EPA and 3M announce phase out of PFOS. News release dated Tuesday May 16. U.S. EPA PFOS Phase Out Announcement

- ^ Rich, N., 2016. The lawyer who became DuPont’s worst nightmare. The New York Times Magazine.

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2018. Fact Sheet: 2010/2015 PFOA Stewardship Program. https://www.epa.gov/assessing-and-managing-chemicals-under-tsca/fact-sheet-20102015-pfoa-stewardship-program

- ^ SERDP/ESTCP website on Per- and Polyfluorinated Substances (PFASs). https://www.serdp-estcp.org/Featured-Initiatives/Per-and-Polyfluoroalkyl-Substances-PFASs

- ^ 9.0 9.1 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2016. Drinking water health advisories for PFOA and PFOS. U.S. EPA Water Health Advisories - PFOA and PFOS

- ^ California State Water Resources Control Board, 2019. PFAS Phased Investigation Approach. https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/pfas/docs/7_investigation_plan.pdf

- ^ Michigan, 2019. PFAS response. Taking Action, Protecting Michigan. Michigan PFAS Action Response Team (MPART).

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2015. Working Towards a Global Emission Inventory of PFASs: Focus on PFCAs – Status Quo and the Way Forward. Paris: Environment, Health and Safety, Environmental Directorate, OECD/UNEP Global PFC Group.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Interstate Technology and Regulatory Council, 2018. Naming Conventions and Physical and Chemical Properties of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). https://pfas-1.itrcweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/pfas_fact_sheet_naming_conventions__3_16_18.pdf

- ^ Interstate Technology Regulatory Council, 2018. PFAS Fact Sheets: Environmental Fate and Transport, Table 3-1. https://pfas-1.itrcweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/ITRCPFASFactSheetFTPartitionTable3-1April18.xlsx

- ^ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, 2018. ToxGuideTM for Perfluoroalkyls. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxguides/toxguide-200.pdf

- ^ Young, C.J., Furdui, V.I., Franklin, J., Koerner, R.M., Muir, D.C. and Mabury, S.A., 2007. Perfluorinated acids in arctic snow: new evidence for atmospheric formation. Environmental Science & Technology, 41(10), 3455-3461. doi: 10.1021/es0626234

- ^ Conder, J.M., Hoke, R.A., Wolf, W.D., Russell, M.H. and Buck, R.C., 2008. Are PFCAs bioaccumulative? A critical review and comparison with regulatory criteria and persistent lipophilic compounds. Environmental Science & Technology, 42(4), 995-1003. doi: 10.1021/es070895g

- ^ Sinclair, E., Mayack, D.T., Roblee, K., Yamashita, N. and Kannan, K., 2006. Occurrence of perfluoroalkyl surfactants in water, fish, and birds from New York State. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 50(3), pp.398-410. doi: 10.1007/s00244-005-1188-z

- ^ Minnesota Department of Health, 2018. Media FAQ: Fish Consumption Advisory, PFOS and Lake Elmo Fish 2018. https://www.co.washington.mn.us/DocumentCenter/View/20895/FAQ-2018-Fish-Consumption-Advisory-NR

- ^ State of Michigan, PFAS Response, Taking Action, Protecting Michigan, 2019. https://www.michigan.gov/pfasresponse/0,9038,7-365-86512_88981_88982---,00.html

- ^ C8 Science Panel, 2012. C8 Probable Link Reports. http://www.c8sciencepanel.org/prob_link.html

- ^ Benbrahim-Tallaa, L., Lauby-Secretan, B. Loomis, D., Guyton, K.Z., Grosse, Y., Bouvard, F. El Ghissassi, V., Guha, N., Mattock, H., Straif, K., 2014. Carcinogenicity of perfluorooctanoic acid, tetrafluoroethylene, dichloromethane, 1,2-dichloropropane, and 1,3-propane sultone. The Lancet Oncology, 15 (9), 924-925. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70316-X

- ^ International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), 2016. Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Lists of Classifications, Volumes 1 to 116. List of Classifications.pdf

- ^ Interstate Technology and Regulatory Council, 2017. History and Use of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). https://pfas-1.itrcweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/pfas_fact_sheet_history_and_use__11_13_17.pdf

- ^ Krafft, M.P. and Riess, J.G., 2015. Selected physicochemical aspects of poly-and perfluoroalkylated substances relevant to performance, environment and sustainability - Part one. Chemosphere, 129, 4-19. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.08.039

- ^ 26.0 26.1 Birnbaum, L.S. and Grandjean, P., 2015. Alternatives to PFAS: Perspectives on the Science. Environmental Health Perspectives, 123(5), A104-A105. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1509944

- ^ Houtz, E.F., 2013. Oxidative measurement of perfluoroalkyl acid precursors: Implications for urban runoff management and remediation of AFFF-contaminated groundwater and soil. Ph.D. Dissertation. Available online at http://escholarship.org/uc/item/4jq0v5qp

- ^ Lang, J.R., Allred, B.M., Peaslee, G.F., Field, J.A. and Barlaz, M.A., 2016. Release of Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Carpet and Clothing in Model Anaerobic Landfill Reactors. Environmental Science & Technology, 50(10), 5024-5032. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b06237

- ^ Interstate Technology and Regulatory Council, 2018. Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF). https://pfas-1.itrcweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/pfas-fact-sheet-afff-10-3-18.pdf

- ^ Darwin, R.L., 2011. Estimated Inventory of PFOS-based Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF). July. https://www.informea.org/sites/default/files/imported-documents/UNEP-POPS-POPRC13FU-SUBM-PFOA-FFFC-3-20180112.En.pdf

- ^ Department of Defense, 2018. Alternatives to Aqueous Film Forming Foam Report to Congress, June. https://www.denix.osd.mil/derp/home/documents/alternatives-to-aqueous-film-forming-foam-report-to-congress/

- ^ Reisch, M.S. “DuPont, Chemours settle PFOA suits” Chem. & Eng. News, Feb. 20, 2017. https://cen.acs.org/articles/95/i8/DuPont-Chemours-settle-PFOA-suits.html

- ^ Bellon, T. 3M, Minnesota settle water pollution claims for $850 million, Reuters, Feb. 20, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-3m-pollution-minnesota/3m-minnesota-settle-water-pollution-claims-for-850-million-idUSKCN1G42UW

- ^ United States District Court of South Carolina. Aqueous Film-Forming Foams (AFFF) Products Liability Litigation MDL No. 2873. https://www.scd.uscourts.gov/mdl-2873/

- ^ Congressional Research Service, 2019. Regulating Drinking Water Contaminants: EPA PFAS Actions. August. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF11219.pdf

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2019. Method 537.1 Determination of Selected Per- and Polyfluorinated Alkyl Substances in Drinking Water by Solid Phase Extraction and Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS/MS). August. https://cfpub.epa.gov/si/si_public_record_Report.cfm?dirEntryId=343042&Lab=NERL

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2019. SW-486 Update VII Announcements, Phase II – PFAS 8372 and 3512, July. https://www.epa.gov/hw-sw846/sw-846-update-vii-announcements

- ^ Houtz, E.F., and Sedlak, D.L., 2012. Oxidative conversion as a means of detecting precursors to perfluoroalkyl acids in urban runoff. Environmental Science & Technology, 46(17), 9342-9349. doi/10.1021/es302274g

- ^ Houtz, E.F., Higgins, C.P., Field, J.A. and Sedlak, D.L., 2013. Persistence of perfluoroalkyl acid precursors in AFFF-impacted groundwater and soil. Environmental Science & Technology, 47(15), 8187-8195. doi: 10.1021/es4018877

- ^ Higgins, C.P., and Luthy, R.G., 2006. Sorption of perfluorinated surfactants on sediments. Environmental Science & Technology, 40(23), 7251-7256. doi: 10.1021/es061000n

- ^ 41.0 41.1 Ferrey, M.L., Wilson, J.T., Adair, C., Su, C., Fine, D.D., Liu, X. and Washington, J.W., 2012. Behavior and fate of PFOA and PFOS in sandy aquifer sediment. Groundwater Monitoring & Remediation, 32(4), 63-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6592.2012.01395.x

- ^ Johnson, R.L., Anschutz, A.J., Smolen, J.M., Simcik, M.F. and Penn, R.L., 2007. The adsorption of perfluorooctane sulfonate onto sand, clay, and iron oxide surfaces. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data, 52(4), 1165-1170. doi: 10.1021/je060285g

- ^ Tseng, N., Wang, N., Szostek, B. and Mahendra, S., 2014. Biotransformation of 6: 2 fluorotelomer alcohol (6: 2 FTOH) by a wood-rotting fungus. Environmental Science & Technology, 48(7), 4012-4020. doi:10.1021/es4057483

- ^ Harding-Marjanovic, K.C., Houtz, E.F., Yi, S., Field, J.A., Sedlak, D.L. and Alvarez-Cohen, L., 2015. Aerobic biotransformation of fluorotelomer thioether amido sulfonate (Lodyne) in AFFF-amended microcosms. Environmental Science & Technology, 49(13), pp.7666-7674. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b01219

- ^ Ellis, D.A., Martin, J.W., De Silva, A.O., Marbury, S.A., Hurley, M.D., Sulbaek Andersen, M.P., and T.J. Wallington, 2004. Degradation of fluorotelomer alcohols: a likely atmospheric source of perfluoronated carboxylic acids. Environmental Science & Technology 38(12), 3316-3321. doi/10.1021/es049860w

- ^ Guelfo, J. 2013. Subsurface fate and transport of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances. Doctor of Philosophy Thesis, Colorado School of Mines. Thesis

- ^ 47.0 47.1 Appleman, T.D., Higgins, C.P., Quinones, O., Vanderford, B.J., Kolstad, C., Zeigler-Holady, J.C. and Dickenson, E.R., 2014. Treatment of poly-and perfluoroalkyl substances in US full-scale water treatment systems. Water Research, 51, 246-255. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.10.067

- ^ Du, Z., Deng, S., Bei, Y., Huang, Q., Wang, B., Huang, J. and Yu, G., 2014. Adsorption behavior and mechanism of perfluorinated compounds on various adsorbents-A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 274, 443-454. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.04.038

- ^ Department of the Navy (DON). 2015. Interim perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) guidance/frequently asked questions. FAQs

- ^ Steinle-Darling, E. and Reinhard, M., 2008. Nanofiltration for trace organic contaminant removal: structure, solution, and membrane fouling effects on the rejection of perfluorochemicals. Environmental Science & Technology, 42 (14), 5292–5297. doi: 10.1021/es703207s

- ^ Huang, Shan and Jaffe, Peter R., 2019. Defluorination of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) by Acidimicrobium sp. Strain A6. Environmental Science and Technology, 53, pp 11410-11419. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.9b04047 https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/acs.est.9b04047

See Also

Relevant Ongoing SERDP/ESTCP Projects:

- In situ treatment train for remediation of perfluoroalkyl contaminated groundwater: In situ chemical oxidation of sorbed contaminants (ISCO-SC). SERDP/ESTCP Project ER-2423

- Quantification of In Situ Chemical Reductive Defluorination (ISCRD) of perfluoroalkyl acids in groundwater impacted by AFFFs. SERDP/ESTCP Project ER-2426

- Bioaugmentation with vaults: Novel In Situ Remediation Strategy for Transformation of Perfluoroalkyl Compounds. SERDP/ESTCP Project ER-2422

- Investigating Electrocatalytic and Catalytic Approaches for In Situ Treatment of Perfluoroalkyl Contaminants in Groundwater. SERDP/ESTCP project ER-2424

- Development of a Novel Approach for In Situ Remediation of Pfc Contaminated Groundwater Systems. SERDP/ESTCP project ER-2425