Difference between revisions of "User:Admin/sandbox"

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

==Quantum yields== | ==Quantum yields== | ||

The proportion of photons absorbed by a given compound that results in its transformation (i.e., via chemical reaction) is known as the reaction’s quantum yield. These are usually determined experimentally. Schwarzenbach et al. (2003)<ref name=":1" /> define quantum yield as: | The proportion of photons absorbed by a given compound that results in its transformation (i.e., via chemical reaction) is known as the reaction’s quantum yield. These are usually determined experimentally. Schwarzenbach et al. (2003)<ref name=":1" /> define quantum yield as: | ||

| − | [[File:PhotolysisEqn1. | + | [[File:PhotolysisEqn1.png|center|500px]] |

In systems involving organic pollutants in natural waters, quantum yields are generally between 0 and 1, since chain reactions resulting in higher quantum yields are rare. Furthermore, quantum yields are not expected to vary significantly with the wavelength of light absorbed, at least over a given absorption band, and can be used to approximate the overall transformation rates of compounds<ref name=":1" />.Where quantum yield can be assumed to be independent of wavelength, it can be expressed as the ratio of the photolysis reaction rate (k<sub>p</sub>) to the rate of light absorption (k<sub>a</sub>): | In systems involving organic pollutants in natural waters, quantum yields are generally between 0 and 1, since chain reactions resulting in higher quantum yields are rare. Furthermore, quantum yields are not expected to vary significantly with the wavelength of light absorbed, at least over a given absorption band, and can be used to approximate the overall transformation rates of compounds<ref name=":1" />.Where quantum yield can be assumed to be independent of wavelength, it can be expressed as the ratio of the photolysis reaction rate (k<sub>p</sub>) to the rate of light absorption (k<sub>a</sub>): | ||

| − | [[File:PhotolysisEqn2. | + | [[File:PhotolysisEqn2.png|center|500px]] |

Thus, if there is an experimentally derived quantum yield available, and if the light absorption rate of a given system can be measured or approximated (e.g., by a spreadsheet or computer program), the direct photolysis rate can be calculated by the above equation. | Thus, if there is an experimentally derived quantum yield available, and if the light absorption rate of a given system can be measured or approximated (e.g., by a spreadsheet or computer program), the direct photolysis rate can be calculated by the above equation. | ||

Reported quantum yields for solutions in distilled water are included in the table below: | Reported quantum yields for solutions in distilled water are included in the table below: | ||

Revision as of 15:17, 16 December 2021

I have installed SandboxLink extension that provides each user their own sandbox accessible through their personal menu bar (top right)

Munitions Constituents – Photolysis

Munitions compounds (MCs), including 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT), hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX), 2,4-dinitroanisole (DNAN), 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO), and nitroguanidine (NQ), absorb light in the UV range and are therefore susceptible to photolysis on soil surfaces and in surface water. Photochemical reactions are important to consider when assessing the environmental impact of MCs since they can yield products that differ from their parent compounds in both toxicity and transport behavior. Quantum yield calculations can aid in predicting the photolysis rates and half-lives of MCs. The photolysis of MCs may be enhanced or inhibited in the presence of compounds that are also excited by UV irradiation.

Related Article(s):

Contributor(s): Dr. Warren Kadoya

Key Resource(s):

- Environmental Organic Chemistry, Chapter 15: Direct Photolysis[1]

- Photochemical Degradation of Composition B and Its Components[2]

- Verification of RDX Photolysis Mechanism[3]

- Photochemical transformation of the insensitive munitions compound 2,4-dinitroanisole[4]

- Photo-transformation of aqueous nitroguanidine and 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one: Emerging munitions compounds[5]

Contents

Introduction

Insensitive munitions, including IMX-101 and IMX-104, are replacing traditional explosives because they are less prone to accidental detonation and therefore safer for military personnel to handle. IMX-101, composed of 2,4-dinitroanisole (DNAN), 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO), and nitroguanidine (NQ), will replace 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) in artillery; IMX-104, composed of DNAN, NTO, and hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX), will replace Composition B (Comp B) in mortars[6]. As both traditional munitions compounds and these insensitive munitions compounds (collectively referred to as MCs) may be deposited onto firing ranges via incomplete detonation, understanding their environmental fate is of concern[7]. Phototransformation due to sunlight exposure is an important fate-controlling parameter for MCs and can occur on the surfaces of solid explosive particles, as shown in Figure 1, as well as in the aqueous phase following MC dissolution by rainwater. Furthermore, MC photolysis can be affected by the presence of natural organic matter and other compounds that are excited by sunlight.

Direct photolysis

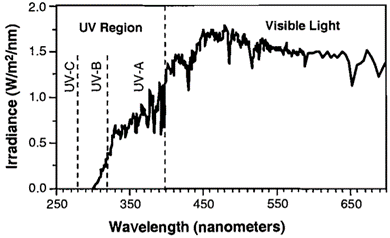

Compounds that absorb ultraviolet (UV, 100-400 nm) and/or visible (Vis, 400-800 nm) light can undergo direct photolysis from sunlight. Light is absorbed in discrete units, or photons, and the energy of these photons is indirectly proportional to the wavelength of the light. When a chemical molecule absorbs a photon, its ground state electrons may become excited. As the excited electrons return to the ground state, they may undergo a chemical reaction that results in transformation. Figure 2 shows that the UV range is further divided into UV-A (315-400 nm), UV-B (280-315 nm), and UV-C (100-280 nm). Because most of UV-C is filtered out by the Earth’s atmosphere, direct photolysis of compounds at the surface primarily involves UV-A and UV-B[9].

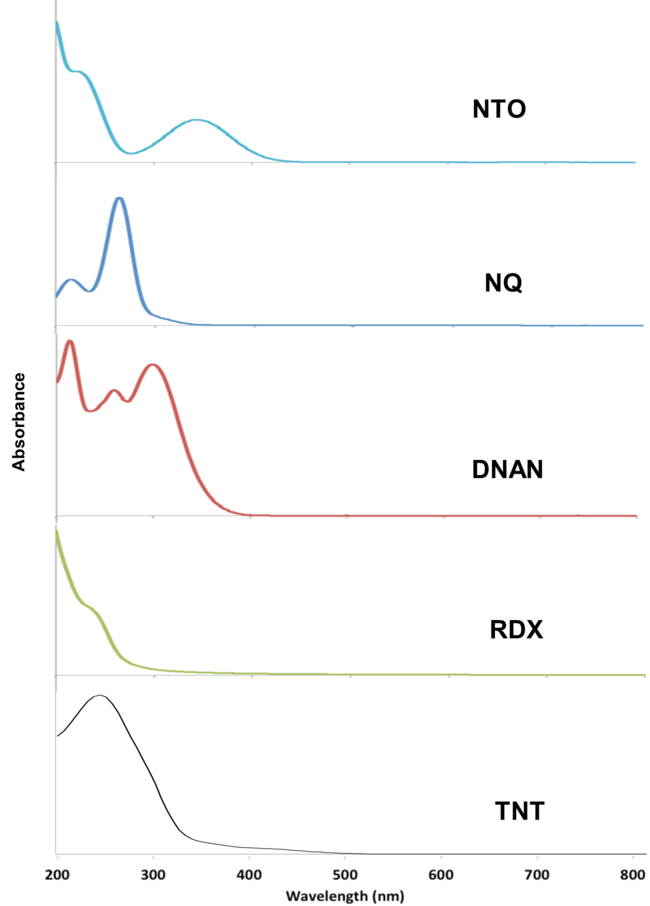

The MCs TNT, RDX, DNAN, NTO, and NQ may undergo direct photolysis since they all absorb light in the UV-Vis range (Figure 3). These graphs convey the probability that the compounds will absorb light at a given wavelength. The absorption maxima correspond to one or more electrons transitioning to an excited state.

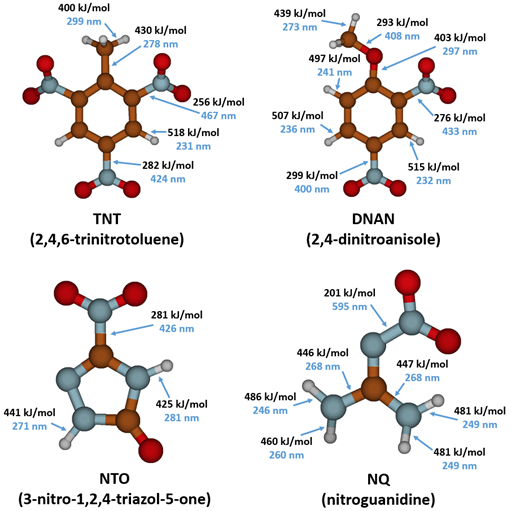

For a chemical bond to break via direct photolysis, a molecule must absorb a photon with higher energy than the energy of the bond. The energy of photons in the UV-Vis range is similar to the bond energies of several single covalent bonds found in organic molecules[1]. Therefore, many of the bonds in TNT, DNAN, NTO, and NQ are susceptible to photolysis from sunlight exposure (Figure 4).

Photolysis products and pathways

The products of the direct photolysis of MCs have been studied in depth, both in photoreactors using UV bulbs emitting light at a given wavelength (Figure 5) or wavelength ranges (including simulated sunlight) and outdoors in natural sunlight. The photolysis of MCs can form mineral products as well as transformation products that may be more toxic than the original compounds.

The formation of pink and red wastewater released by some ammunition plants led to investigations into the photolysis products of TNT starting in the 1970s. Laboratory experiments observed rapid phototransformation from sunlight in natural waters, some with half-lives less than an hour[12]. Numerous photolysis products of TNT have been reported and include, but are not limited to, 2-amino-4,6-dinitrobenzoic acid, 2,4,6-trinitrobenzaldehyde, 4,6-dinitroanthranil, 2,4,6-trinitrobenzonitrile, 2,4,6-trinitrobenzoic acid, 1,3,5-trinitrobenzene (TNB), 2,4,6-trinitrobenzyl alcohol, and an array of azo and azoxy compounds[2][13][14][15][16].

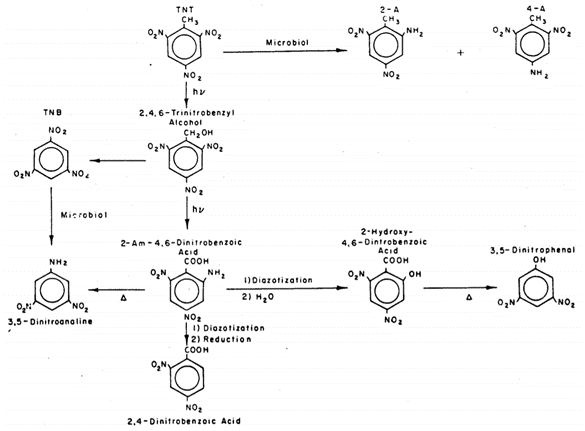

The mechanism of TNT photolysis is not completely understood as numerous products are formed, many of which are not readily synthesized or purchased[16]. However, evidence suggests that TNT is initially excited to a triplet state by UV light[12]. Figure 6 shows a proposed environmental reaction pathway for TNT that combines photo- and biological reactions based on studies in waste disposal lagoons[15].

The aquatic toxicity of phototransformed TNT solutions and ammunition wastewaters was not found to be significantly different from that of untransformed TNT[18][19]. Although TNT phototransformation products tend to be more toxic than TNT, the relatively low product formation coupled with the disappearance of TNT may explain these results.

RDX photolysis products detected in aqueous systems include nitrite, nitrate, ammonia, formaldehyde, formic acid, formamide, nitrous oxide, and 4-nitro-2,4-diazabutanal[20][21][22][23]. Stable phototransformation products also detected include nitroso compounds MNX (hexahydro-1-nitroso-3,5-dinitro-1,3,5-triazine), DNX (hexahydro-1,3-dinitroso-5-nitro-1,3,5-triazine), and TNX (hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitroso-1,3,5-triazine), which contain one, two, and three nitroso groups each, respectively, in place of the nitro groups. The formation of unsaturated MUX (1,3-dinitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1,3,5-triazine) was also reported (Figure 7)[3].

Peyton et al. (1999) compiled experimental results for RDX photolysis in a proposed reaction mechanism (Figure 7)[3]. The most common first step is the breaking of an N-N bond between a nitro group and a nitrogen atom in the heterocyclic ring, resulting in two radical species (structure (R) in the center and an NO2 radical). They hypothesize that the NO2 radical can become an NO radical that may then recombine with structure (R), giving nitroso product MNX. This process can be repeated to form products DNX and TNX (i.e., via cleavage of the other N-N bonds, as shown in the formation of structure [R2]). The formation of MUX, containing an unsaturation (C=N double bond in the ring) was likely due to the loss of HNO2 from RDX. Other products could include a combination of nitroso groups and unsaturations. The unsaturated compounds, including MUX, are expected to undergo hydrolysis, forming many smaller products (e.g., nitrite and formaldehyde)[3][23]. One of the major products of RDX photolysis is nitrate, a common groundwater pollutant of concern, despite being much less toxic than RDX[21]. The risk posed by the other toxic products should be evaluated, though they are formed in smaller quantities.

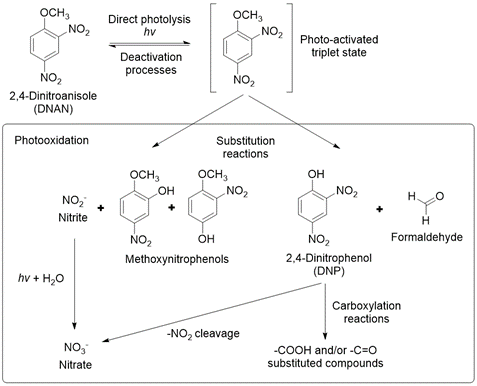

The products formed from DNAN photolysis include nitrate, nitrite, 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP), 2-methoxy-5-nitrophenol, 4-methoxy-3-nitrophenol, [[1]], formaldehyde, and formic acid[4][24][25].Rao et al. (2013) proposed a pathway for DNAN photolysis with photooxidation as the primary mechanism (Figure 8)[4]. According to the computational modeling of DNAN bond energies, the C-N bonds and the C-O bond of the methoxy group are most susceptible to photolysis (Figure 4)[26]. This is in agreement with the transformation products formed. Once DNAN is excited to a photo-activated triplet state, OH- in solution can displace either of its nitro groups via an SN2 reaction to form a methoxynitrophenol. This releases nitrite, which can then form nitrate through further photooxidation. DNP could form via O-demethylation of DNAN, which could occur by hydroxylation of the methyl group and the release of formaldehyde[27]. Formaldehyde or formic acid may react with NH2 groups in methoxynitroanilines or aminonitrophenols to produce formamide derivatives[25].

Ecotoxicity estimates predict that DNAN phototransformation products are less toxic than DNAN, except for DNP, which is more toxic and known to uncouple oxidative phosphorylation[4][26]. However, upon further photolysis, DNP was shown to degrade into nitrocatechol and nitrite[4][25].

NTO

Aqueous NTO formed ammonium, nitrate, nitrite, and a urazole intermediate when irradiated with UV light[5][28]. A significant amount of the original NTO mass was not recovered. This may be due, in part, to the volatilization of gaseous species since bubbles formed in the irradiated solutions. A proposed pathway for NTO photolysis is shown in Figure 9[5]. The first step is the breaking of the C-NO2 bond, which has the lowest bond energy (Figure 4). This forms a nitro radical and a triazolone radical. The nitro radical can then form nitrite and nitrate, and the triazolone radical can form urazole upon reaction with water. Urazole and/or NTO may undergo hydrolysis that breaks open the heterocyclic ring and ultimately forms degradation products such as ammonium and carbon dioxide gas. In aquatic toxicity studies, UV-irradiated NTO was found to be up to 100 times more toxic than non-irradiated NTO[19][28]. The specific photolysis products responsible for this increase in toxicity are still being investigated.

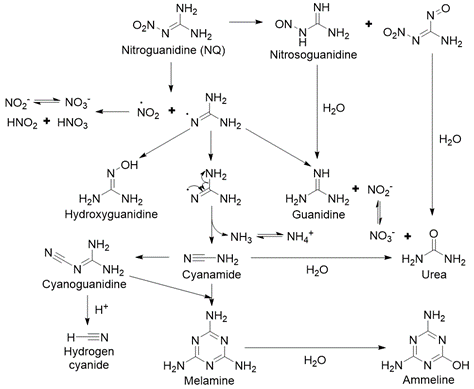

NQ The major products formed from NQ photolysis are nitrate, nitrite, guanidine, and urea. Minor products include cyanamide, cyanoguanidine, ammonium, melamine, ammeline, and cyanide[5][28][29][30][31]. Nitrosoguanidine and hydroxyguanidine were identified as intermediates that were further phototransformed30,31. A proposed pathway for NQ photolysis is shown in Figure 10[5]. The weakest bond is the N-NO2 bond (Figure 4), and when it is cleaved, it forms nitro and guanidine radicals. The nitro radical can form nitrite and nitrate. The guanidine radical, upon reaction with a hydrogen ion or a water molecule, can form guanidine or hydroxyguanidine, respectively. Ammonia and cyanamide can also form from the breakdown of the guanidine radical. Cyanamide can then undergo either dimerization to form cyanoguanidine or hydrolysis to form urea. Melamine is a trimer of cyanamide and ammeline is a hydrolysis product of melamine. Cyanide may be formed from cyanoguanidine under acidic conditions[19].

UV-irradiated NQ was found to be orders of magnitude more toxic to aquatic organisms than NQ that was not irradiated[19][28][32][33]. Furthermore, it was responsible for most of the toxicity of irradiated IMX-101. Moores et al. (2020) found that guanidine, nitrite, ammonia, nitrosoguanidine, and cyanide produced from NQ photolysis were each more toxic to Daphnia pulex than NQ, with nitrite and cyanide contributing the most to the toxicity[28]. When adding up the individual toxicities caused by these photolysis products, only 25% of the overall toxicity caused by exposure to irradiated NQ was accounted for. This implied that additional, unidentified products with greater toxicity to D. pulex formed and/or that exposure to all the products at once created a synergistic toxic effect.

Photolysis kinetics

In dilute solutions, the direct photolysis of a compound may be described as a pseudo first-order process, in which the log of the compound concentration decreases linearly with time. In contrast, when the compound concentration is high enough that it absorbs most of the incident light, the photolysis rate no longer depends on the compound concentration, and the process may be described as zero order[1][34]. First-order kinetics were reported in studies irradiating MCs at 1 mg L-1, whereas zero-order kinetics were reported for MCs irradiated at higher initial concentrations[4][8][12][29][35]. The phase of an MC can impact its photolysis rate, as aqueous RDX was found to transform significantly faster than solid RDX[21]. In addition, the half-lives of UV-irradiated compounds are highly dependent on sunlight exposure and intensity, which vary with time (of day and year) and location (latitude and altitude). Therefore, it is more useful to describe photolysis in terms of quantum yields rather than reaction rates or half-lives, since they account for differences in experimental setup and irradiance and are more readily comparable[34].

Quantum yields

The proportion of photons absorbed by a given compound that results in its transformation (i.e., via chemical reaction) is known as the reaction’s quantum yield. These are usually determined experimentally. Schwarzenbach et al. (2003)[1] define quantum yield as:

In systems involving organic pollutants in natural waters, quantum yields are generally between 0 and 1, since chain reactions resulting in higher quantum yields are rare. Furthermore, quantum yields are not expected to vary significantly with the wavelength of light absorbed, at least over a given absorption band, and can be used to approximate the overall transformation rates of compounds[1].Where quantum yield can be assumed to be independent of wavelength, it can be expressed as the ratio of the photolysis reaction rate (kp) to the rate of light absorption (ka):

Thus, if there is an experimentally derived quantum yield available, and if the light absorption rate of a given system can be measured or approximated (e.g., by a spreadsheet or computer program), the direct photolysis rate can be calculated by the above equation. Reported quantum yields for solutions in distilled water are included in the table below:

| MC | Light source | Reaction quantum yield |

| TNT | 313 and 366 nm | 2.7 x 10-3 [12] |

| TNT | Simulated sunlight | 2.6 x 10-3 [16] |

| RDX | 313 nm | 1.6 x 10-1 [14] |

| DNAN | 312 nm max (280-315 nm) | 3.7 x 10-4 [4] |

| DNAN | 350 nm max (316-400 nm) | 2.9 x 10-4 [4] |

| DNAN | Simulated sunlight | 1.1 x 10-4 [4] |

| DNAN | Sunlight | 3.2 x 10-3 [35] |

| NTO | Sunlight | 5.9 x 10-5 [35] |

| NQ | Sunlight | 1.0 x 10-2 [35] |

| NQ | Sunlight | 1.02 x 10-2, 1.26 x 10-2 [30] |

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Schwarzenbach, R.P., Gschwend, P.M., and Imboden, D.M., 2002. Chapter 15, Direct Photolysis. In: Schwarzenbach, R.P., Gschwend, P.M., and Imboden, D.M. (eds). Environmental Organic Chemistry. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, pp. 611-654. doi:10.1002/0471649643.ch15

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Pennington, J.C., Thorn, K.A., Co, L.G., MacMillan, D.K., Yost, S., and Laubscher, R.D., 2007. Photochemical Degradation of Composition B and Its Components. U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC)/ Environmental Laboratory (EL) TR-07-16. Report pdf

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Peyton, G.R., LeFaivre, M.H., and Maloney, S.W., 1999. Verification of RDX photolysis mechanism. U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC)/ Construction Engineering Research Laboratory (CERL) TR 99/93. Report pdf

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 Rao, B., Wang, W., Cai, Q., Anderson, T., and Gu, B., 2013. Photochemical Transformation of The Insensitive Munitions Compound 2,4-Dinitroanisole. Science of The Total Environment, 443, pp. 692-699. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.11.033

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Becher, J.B., Beal, S.A., Taylor, S., Dontsova, K., Wilcox, D.E., 2019. Photo-transformation of aqueous nitroguanidine and 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one: Emerging munitions compounds. Chemosphere, 228, pp. 418-426. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.04.131

- ^ BAE Systems, 2021. Making explosives safer

- ^ Pennington, J.C., Silverblatt, B., Poe, K., Hayes, C.A., and Yost, S, 2008. Explosive residues from low-order detonations of heavy artillery and mortar rounds. Soil and Sediment Contamination: An International Journal, 17(5), pp. 533-546. doi: 10.1080/15320380802306669

- ^ 8.0 8.1 Dontsova, K., Taylor S., Pesce-Rodriguez, R., Brusseau, M., Arthur, J., Mark, N., Walsh, M., Lever, J., and Simunek, J., 2014. Dissolution of NTO, DNAN, and insensitive munitions formulations and their fates in soils. U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC)/ Cold Region Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) TR-14-23. Report pdf

- ^ 9.0 9.1 Brennan, P., and Fedor, C., 1994. Sunlight, UV, & accelerated weathering. Q-Lab Corporation, Technical Bulletin LU-0822. Paper pdf

- ^ Taylor, S., Becher, J., Beal, S., Ringelberg, D., Spanggord, R., and Dontsova, K., 2017. Photo-transformation of explosives and their constituents. In: The Environmental Aspects of Munitions Workshop, Joint Army-Navy-NASA-Air Force (JANNAF), Kansas City, MO, May 22, 2017.

- ^ Dontsova, K., Taylor, S., Brusseau, M. L., Simunek, J., and Hunt, E., 2017. Influence of climate on dissolution and phototransformation of NTO and DNAN from insensitive munitions and their fate in soils. In: Poster, the SERDP-ESTCP symposium, Washington, D.C., November 28-30, 2017. The Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP) and Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP).

- ^ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Mabey, W.R., Tse, D., Baraze, A., and Mill, T., 1983. Photolysis of nitroaromatics in aquatic systems. I. 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene. Chemosphere, 12(1), pp. 3-16. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(83)90174-1

- ^ Burlinson, N.E., Kaplan, L.A., and Adams, C.E., 1983. Photochemistry of TNT: Investigation of the ‘pink water’ problem. Naval Ordnance Laboratory, pp. 73-172. Report pdf

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Spanggord, R.J., Mill, T., Chou, T., Mabey, W.R., Smith, J.H., and Lee, S., 1980. Environmental fate studies on certain munition wastewater constituents. Phase II - Laboratory studies. U S Army Biomedical Research and Development Laboratory. Report pdf

- ^ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Spanggord, R.J., Mabey, W.R., Mill, T., Tsong-Wen, C., Smith, J.H., Lee, S., and Roberts, D., 1983. Environmental fate studies on certain munitions wastewater constituents: Phase IV - Lagoon model studies. U S Army Biomedical Research and Development Laboratory. Report pdf

- ^ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Luning Prak D.J., Breuer J.E.T., Rios E.A., Jedlicka E.E., and O'Sullivan D.W., 2017. Photolysis of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene in seawater and estuary water: Impact of pH, temperature, salinity, and dissolved organic matter. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 114(2), pp. 977-986. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.10.073

- ^ Walsh, M.E., 1990. Environmental Transformation Products of Nitroaromatics and Nitramines: Literature Review and Recommendations for Analytical Method Development. US Army Corps of Engineers Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory. Report pdf

- ^ Liu, D.H.W., Spanggord, R.J., Bailey, H.C., Javitz, H.S., and Jones, D.C.L., 1983. Toxicity of TNT Wastewaters to Aquatic Organisms. Volume 1. Acute Toxicity of LAP Wastewater and 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene. U S Army Medical Bioengineering Research and Development Laboratory. Report pdf

- ^ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Kennedy, A.J., Poda, A.R., Melby, N.L., Moores, L.C., Jordan, S.M., Gust, K.A., and Bednar, A.J., 2017. Aquatic toxicity of photo-degraded insensitive munition 101 (IMX-101) constituents. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 36(8), pp.2050-2057. doi: 10.1002/etc.3732

- ^ Just, C.L., and Schnoor, J.L., 2004. Phytophotolysis of Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) in Leaves of Reed Canary Grass. Environmental Science and Technology, 38(1), pp. 290-295. doi: 10.1021/es034744z

- ^ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Bordeleau, G., Martel, R., Ampleman, G., and Thiboutot, S., 2013. Photolysis of RDX and nitroglycerin in the context of military training ranges. Chemosphere, 93(1), pp. 14-19. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.04.048

- ^ Glover, D.J., and Hoffsommer, J.C., 1979. Photolyis of RDX in Aqueous Solution, With and Without Ozone. Naval Service Weapons Center, NSWC/WOL TR 78-175. Report pdf

- ^ 23.0 23.1 Hawari, J., Halasz, A., Groom, C., Deschamps S., Paquet, L., Beaulieu, C., and Corriveau, A., 2002. Photodegradation of RDX in Aqueous Aolution: A Mechanistic Probe for Biodegradation with Rhodococcus sp. Environmental Science and Technology, 36(23), pp. 5117-5123. doi: 10.1021/es020775

- ^ Taylor, S., Walsh, M.E., Becher, J.B., Ringelberg, D.B., Mannes, P.Z., and Gribble, G.W., 2016. Photo-degradation of 2,4-dinitroanisole (DNAN): An emerging munitions compound. Chemosphere, 167, pp.193-203. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.09.142

- ^ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Hawari, J., Monteil-Rivera, F., Perreault, N., Halasz, A., Paquet, L., Radovic-Hrapovic, Z., Deschamps, S., Thiboutot, S., Ampleman, G., 2015. Environmental fate of 2, 4-dinitroanisole (DNAN) and its reduced products. Chemosphere, 119, pp.16-23. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.05.047

- ^ 26.0 26.1 Qin, C., Abrell, L., Troya, D., Hunt, E., Taylor, S., and Dontsova, K., 2021. Outdoor dissolution and photodegradation of insensitive munitions formulations IMX-101 and IMX-104: Photolytic transformation pathway and mechanism study. Chemosphere, 280, 130672. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130672

- ^ Studziński. W., Gackowska, A., Przybyłek, M., Gaca, J., 2017. Studies on the formation of formaldehyde during 2-ethylhexyl 4-(dimethylamino)benzoate demethylation in the presence of reactive oxygen and chlorine species. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 24(9), pp. 8049-8061. doi:10.1007/s11356-017-8477-8 Article pdf

- ^ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 Moores, L.C., Kennedy, A.J., May, L., Jordan, S.M., Bednar A. J., Jones S.J., Henderson D.L., Gurtowski L., and Gust, K.A., 2020. Identifying degradation products responsible for increased toxicity of UV-degraded insensitive munitions. Chemosphere, 240, 124958. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124958

- ^ 29.0 29.1 Burrows, W.D., Schmidt, M.O., Chyrek, R.H., and Noss, C.I., 1988. Photochemistry of aqueous nitroguanidine. US Army Biomedical Research and Development Laboratory. Report pdf

- ^ 30.0 30.1 Haag, W.R., Spanggord, R., Mill, T., Podoll, R.T., Chou, T., Tse, D.S., and Harper J.C., 1990. Aquatic environmental fate of nitroguanidine. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 9(11), pp. 1359-1367. doi: 10.1002/etc.5620091105

- ^ Noss, C.I., and Chyreck, R.H., 1984. Nitroguanidine Wastewater Pollution Control Technology: Phase III. Treatment with Ultraviolet Radiation, Ozone, And Hydrogen Peroxide. U S Army Medical Bioengineering Research and Development Laboratory. Report pdf

- ^ Gust, K.A., Stanley, J.K., Wilbanks, M.S., Mayo, M.L., Chappell P., Jordan, S.M., Moores, L.C., Kennedy, A.J., and Barker, N.D., 2017.. The increased toxicity of UV-degraded nitroguanidine and IMX-101 to zebrafish larvae: Evidence implicating oxidative stress. Aquatic Toxicology, 190, pp. 228-245. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2017.07.004

- ^ van der Schalie, W.H.,1985. The toxicity of nitroguanidine and photolyzed nitroguanidine to freshwater aquatic organisms. U S Army Medical Bioengineering Research and Development Laboratory. Report pdf

- ^ 34.0 34.1 Logan, S.R., 1997. Does a photochemical reaction have a reaction order? Journal of Chemical Education, 74(11), pp.1303. doi: 10.1021/ed074p1303

- ^ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 Moores, L.C., Jones, S.J., George, G.W., Henderson, D.L., and Schutt, T.C., 2020. Photo degradation kinetics of insensitive munitions constituents nitroguanidine, nitrotriazolone, and dinitroanisole in natural waters. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, 386, 112094. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2019.112094