|

|

| (159 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | ==Thermal Conduction Heating for Treatment of PFAS-Impacted Soil== | + | ==''In Situ'' Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE)== |

| − | Removal of [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] compounds from impacted soils is challenging due to the modest volatility and varying properties of most PFAS compounds. Thermal treatment technologies have been developed for treatment of semi-volatile compounds in soils such as dioxins, furans, poly-aromatic hydrocarbons and poly-chlorinated biphenyls at temperatures near 325°C. In controlled bench-scale testing, complete removal of targeted PFAS compounds to concentrations below reporting limits of 0.5 µg/kg was demonstrated at temperatures of 400°C<ref name="CrownoverEtAl2019"> Crownover, E., Oberle, D., Heron, G., Kluger, M., 2019. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances thermal desorption evaluation. Remediation Journal, 29(4), pp. 77-81. [https://doi.org/10.1002/rem.21623 doi: 10.1002/rem.21623]</ref>. Three field-scale thermal PFAS treatment projects that have been completed in the US include an in-pile treatment demonstration, an ''in situ'' vadose zone treatment demonstration and a larger scale treatment demonstration with excavated PFAS-impacted soil in a constructed pile. Based on the results, thermal treatment temperatures of at least 400°C and a holding time of 7-10 days are recommended for reaching local and federal PFAS soil standards. The energy requirement to treat typical wet soil ranges from 300 to 400 kWh per cubic yard, exclusive of heat losses which are scale dependent. Extracted vapors have been treated using condensation and granular activated charcoal filtration, with thermal and catalytic oxidation as another option which is currently being evaluated for field scale applications. Compared to other options such as soil washing, the ability to treat on site and to treat all soil fractions is an advantage.

| + | The ''in situ'' Toxicity Identification Evaluation system is a tool to incorporate in weight-of-evidence studies at sites with numerous chemical toxicant classes present. The technology works by continuously sampling site water, immediately fractionating the water using diagnostic sorptive resins, and then exposing test organisms to the water to observe toxicity responses with minimal sample manipulation. It is compatible with various resins, test organisms, and common acute and chronic toxicity tests, and can be deployed at sites with a wide variety of physical and logistical considerations. |

| | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> |

| | | | |

| | '''Related Article(s):''' | | '''Related Article(s):''' |

| | | | |

| − | *[[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] | + | *[[Contaminated Sediments - Introduction]] |

| − | *[[Thermal Conduction Heating (TCH)]] | + | *[[Contaminated Sediment Risk Assessment]] |

| | + | *[[Passive Sampling of Sediments]] |

| | + | *[[Sediment Porewater Dialysis Passive Samplers for Inorganics (Peepers)]] |

| | | | |

| − | '''Contributors:''' Gorm Heron, Emily Crownover, Patrick Joyce, Ramona Iery | + | '''Contributors:''' Dr. G. Allen Burton Jr., Austin Crane |

| | | | |

| − | '''Key Resource:''' | + | '''Key Resources:''' |

| − | *Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances thermal desorption evaluation<ref name="CrownoverEtAl2019"/> | + | *A Novel In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) System for Determining which Chemicals Drive Impairments at Contaminated Sites<ref name="BurtonEtAl2020">Burton, G.A., Cervi, E.C., Meyer, K., Steigmeyer, A., Verhamme, E., Daley, J., Hudson, M., Colvin, M., Rosen, G., 2020. A novel In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) System for Determining which Chemicals Drive Impairments at Contaminated Sites. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 39(9), pp. 1746-1754. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.4799 doi: 10.1002/etc.4799]</ref> |

| | + | *An in situ toxicity identification and evaluation water analysis system: Laboratory validation<ref name="SteigmeyerEtAl2017">Steigmeyer, A.J., Zhang, J., Daley, J.M., Zhang, X., Burton, G.A. Jr., 2017. An in situ toxicity identification and evaluation water analysis system: Laboratory validation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 36(6), pp. 1636-1643. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.3696 doi: 10.1002/etc.3696]</ref> |

| | + | *Sediment Toxicity Identification Evaluation (TIE) Phases I, II, and III Guidance Document<ref>United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2007. Sediment Toxicity Identification Evaluation (TIE) Phases I, II, and III Guidance Document, EPA/600/R-07/080. 145 pages. [https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPURL.cgi?Dockey=P1003GR1.txt Free Download] [[Media: EPA2007.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> |

| | + | *In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) Technology for Assessing Contaminated Sediments, Remediation Success, Recontamination and Source Identification<ref>In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) Technology for Assessing Contaminated Sediments, Remediation Success, Recontamination and Source Identification [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/88a8f9ba-542b-4b98-bfa4-f693435535cd/er18-1181-project-overview Project Website] [[Media: ER18-1181Ph.II.pdf | Final Report.pdf]]</ref> |

| | | | |

| | ==Introduction== | | ==Introduction== |

| − | [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] have become prominent emerging contaminants in soil and groundwater. Soil source zones have been identified at locations where the chemicals were produced, handled or used. Few effective options exist for treatments that can meet local and federal soil standards. Over the past 30 plus years, thermal remediation technologies have grown from experimental and innovative prospects to mature and accepted solutions deployed effectively at many sites. More than 600 thermal case studies have been summarized by Horst and colleagues<ref name="HorstEtAl2021">Horst, J., Munholland, J., Hegele, P., Klemmer, M., Gattenby, J., 2021. In Situ Thermal Remediation for Source Areas: Technology Advances and a Review of the Market From 1988–2020. Groundwater Monitoring & Remediation, 41(1), p. 17. [https://doi.org/10.1111/gwmr.12424 doi: 10.1111/gwmr.12424] [[Media: gwmr.12424.pdf | Open Access Manuscript]]</ref>. [[Thermal Conduction Heating (TCH)]] has been used for higher temperature applications such as removal of [[1,4-Dioxane]]. This article reports recent experience with TCH treatment of PFAS-impacted soil.

| + | In waterways impacted by numerous naturally occurring and anthropogenic chemical stressors, it is crucial for environmental practitioners to be able to identify which chemical classes are causing the highest degrees of toxicity to aquatic life. Previously developed methods, including the Toxicity Identification Evaluation (TIE) protocol developed by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)<ref>Norberg-King, T., Mount, D.I., Amato, J.R., Jensen, D.A., Thompson, J.A., 1992. Toxicity identification evaluation: Characterization of chronically toxic effluents: Phase I. Publication No. EPA/600/6-91/005F. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development. [https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-09/documents/owm0255.pdf Free Download from US EPA] [[Media: usepa1992.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>, can be confounded by sample manipulation artifacts and temporal limitations of ''ex situ'' organism exposures<ref name="BurtonEtAl2020"/>. These factors may disrupt causal linkages and mislead investigators during site characterization and management decision-making. The ''in situ'' Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) technology was developed to allow users to strengthen stressor-causality linkages and rank chemical classes of concern at impaired sites, with high degrees of ecological realism. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Target Temperature and Duration==

| + | The technology has undergone a series of improvements in recent years, with the most recent prototype being robust, operable in a wide variety of site conditions, and cost-effective compared to alternative site characterization methods<ref>Burton, G.A. Jr., Nordstrom, J.F., 2004. An in situ toxicity identification evaluation method part I: Laboratory validation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(12), pp. 2844-2850. [https://doi.org/10.1897/03-409.1 doi: 10.1897/03-409.1]</ref><ref>Burton, G.A. Jr., Nordstrom, J.F., 2004. An in situ toxicity identification evaluation method part II: Field validation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(12), pp. 2851-2855. [https://doi.org/10.1897/03-468.1 doi: 10.1897/03-468.1]</ref><ref name="BurtonEtAl2020"/><ref name="SteigmeyerEtAl2017"/>. The latest prototype can be used in any of the following settings: in marine, estuarine, or freshwater sites; to study surface water or sediment pore water; in shallow waters easily accessible by foot or in deep waters only accessible by pier or boat. It can be used to study sites impacted by a wide variety of stressors including ammonia, [[Metal and Metalloid Contaminants | metals]], pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB), [[Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) | polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH)]], and [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)]], among others. The technology is applicable to studies of acute toxicity via organism survival or of chronic toxicity via responses in growth, reproduction, or gene expression<ref name="BurtonEtAl2020"/>. |

| − | PFAS behave differently from most other organics subjected to TCH treatment. While the boiling points of individual PFAS fall in the range of 150-400°C, their chemical and physical behavior creates additional challenges. Some PFAS form ionic species in certain pH ranges and salts under other chemical conditions. This intricate behavior and our limited understanding of what this means for our ability to remove the PFAS from soils means that direct testing of thermal treatment options is warranted. Crownover and colleagues<ref name="CrownoverEtAl2019"/> subjected PFAS-laden soil to bench-scale heating to temperatures between 200 and 400°C which showed strong reductions of PFAS concentrations at 350°C and complete removal of many PFAS compounds at 400°C. The soil concentrations of targeted PFAS were reduced to nearly undetectable levels in this study.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Heating Method== | + | ==System Components and Validation== |

| − | For semi-volatile compounds such as dioxins, furans, poly-chlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and Poly-Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH), thermal conduction heating has evolved as the dominant thermal technology because it is capable of achieving soil temperatures higher than the boiling point of water, which are necessary for complete removal of these organic compounds. Temperatures between 200 and 500°C have been required to achieve the desired reduction in contaminant concentrations<ref name="StegemeierVinegar2001">Stegemeier, G.L., Vinegar, H.J., 2001. Thermal Conduction Heating for In-Situ Thermal Desorption of Soils. Ch. 4.6, pp. 1-37. In: Chang H. Oh (ed.), Hazardous and Radioactive Waste Treatment Technologies Handbook, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. ISBN 9780849395864 [[Media: StegemeierVinegar2001.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. TCH has become a popular technology for PFAS treatment because temperatures in the 400°C range are needed.

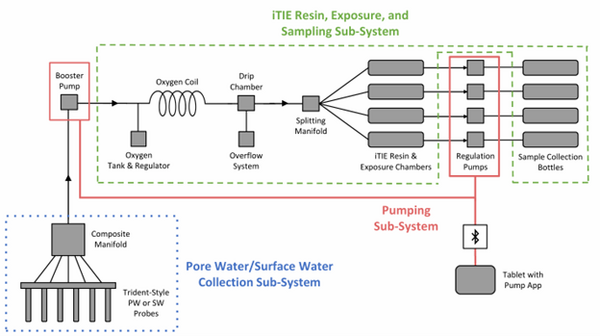

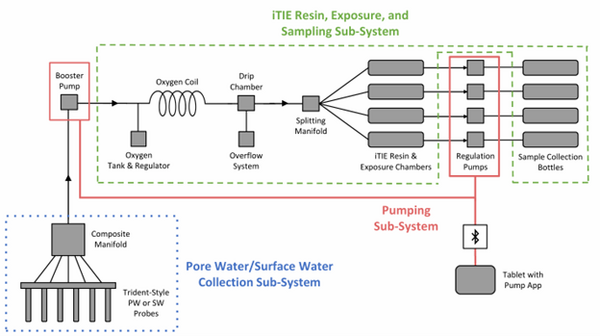

| + | [[File: CraneFig1.png | thumb | 600 px | Figure 1: A schematic diagram of the iTIE system prototype. The system is divided into three sub-systems: 1) the Pore Water/Surface Water Collection Sub-System (blue); 2) the Pumping Sub-System (red); and 3) the iTIE Resin, Exposure, and Sampling Sub-System (green). Water first enters the system through the Pore Water/Surface Water Collection Sub-System. Porewater can be collected using Trident-style probes, or surface water can be collected using a simple weighted probe. The water is composited in a manifold before being pumped to the rest of the iTIE system by the booster pump. Once in the iTIE Resin, Exposure, and Sampling Sub-System, the water is gently oxygenated by the Oxygen Coil, separated from gas bubbles by the Drip Chamber, and diverted to separate iTIE Resin and Exposure Chambers (or iTIE units) by the Splitting Manifold. Water movement through each iTIE unit is controlled by a dedicated Regulation Pump. Finally, the water is gathered in Sample Collection bottles for analysis.]] |

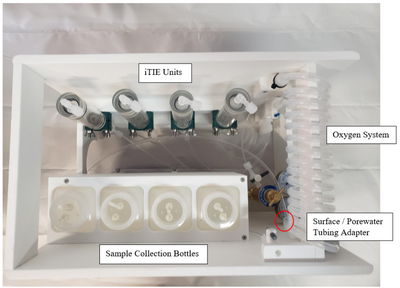

| | + | The latest iTIE prototype consists of an array of sorptive resins that differentially fractionate sampled water, and a series of corresponding flow-through organism chambers that receive the treated water ''in situ''. Resin treatments can be selected depending on the chemicals suspected to be present at each site to selectively sequester certain chemical of concern (CoC) classes from the whole water, leaving a smaller subset of chemicals in the resulting water fraction for chemical and toxicological characterization. Test organism species and life stages can also be chosen depending on factors including site characteristics and study goals. In the full iTIE protocol, site water is continuously sampled either from the sediment pore spaces or the water column at a site, gently oxygenated, diverted to different iTIE units for fractionation and organism exposure, and collected in sample bottles for off-site chemical analysis (Figure 1). All iTIE system components are housed within waterproof Pelican cases, which allow for ease of transport and temperature control. |

| | | | |

| − | The energy source for TCH can be electricity (most commonly used), or fossil fuels (typically gas, diesel or fuel oil). Electrically powered TCH offers the largest flexibility for power input which also can be supplied by renewable and sustainable energy sources.

| + | ===Porewater and Surface Water Collection Sub-system=== |

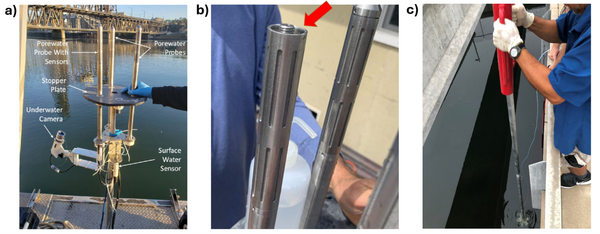

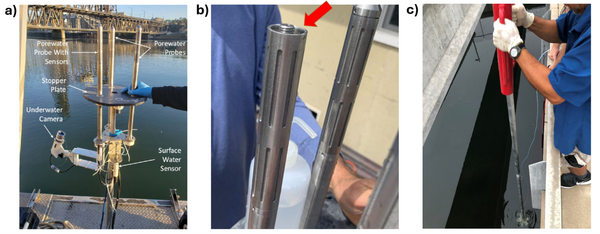

| | + | [[File: CraneFig2.png | thumb | 600 px | Figure 2: a) Trident probe with auxiliary sensors attached, b) a Trident probe with end caps removed (the red arrow identifies the intermediate space where glass beads are packed to filter suspended solids), c) a Trident probe being installed using a series of push poles and a fence post driver]] |

| | + | Given the importance of sediment porewater to ecosystem structure and function, investigators may employ the iTIE system to evaluate the toxic effects associated with the impacted sediment porewater. To accomplish this, the iTIE system utilizes the Trident probe, originally developed for Department of Defense site characterization studies<ref>Chadwick, D.B., Harre, B., Smith, C.F., Groves, J.G., Paulsen, R.J., 2003. Coastal Contaminant Migration Monitoring: The Trident Probe and UltraSeep System. Hardware Description, Protocols, and Procedures. Technical Report 1902. Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center.</ref>. The main body of the Trident is comprised of a stainless-steel frame with six hollow probes (Figure 2). Each probe contains a layer of inert glass beads, which filters suspended solids from the sampled water. The water is drawn through each probe into a composite manifold and transported to the rest of the iTIE system using a high-precision peristaltic pump. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Energy Usage==

| + | The Trident also includes an adjustable stopper plate, which forms a seal against the sediment and prevents the inadvertent dilution of porewater samples with surface water. (Figure 2). Preliminary laboratory results indicate that the Trident is extremely effective in collecting porewater samples with minimal surface water infiltration in sediments ranging from coarse sand to fine clay. Underwater cameras, sensors, passive samplers, and other auxiliary equipment can be attached to the Trident probe frame to provide supplemental data. |

| − | Treating PFAS-impacted soil with heat requires energy to first bring the soil and porewater to the boiling point of water, then to evaporate the porewater until the soil is dry, and finally to heat the dry soil up to the target treatment temperature. The energy demand for wet soils falls in the 300-400 kWh/cy range, dependent on porosity and water saturation. Additional energy is consumed as heat is lost to the surroundings and by vapor treatment equipment, yielding a typical usage of 400-600 kWh/cy total for larger soil treatment volumes. Wetter soils and small treatment volumes drive the energy usage towards the higher number, whereas larger soil volumes and dry soil can be treated with less energy.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Vapor Treatment==

| + | Alternatively, practitioners may employ the iTIE system to evaluate site surface water. To sample surface water, weighted intake tubes can collect surface water from the water column using a peristaltic pump. |

| − | During the TCH process a significant fraction of the PFAS compounds are volatilized by the heat and then removed from the soil by vacuum extraction. The vapors must be treated and eventually discharged while meeting local and/or federal standards. Two types of vapor treatment have been used in past TCH applications for organics: (1) thermal and catalytic oxidation and (2) condensation followed by granular activated charcoal (GAC) filtration. Due to uncertainties related to thermal destruction of fluorinated compounds and future requirements for treatment temperature and residence time, condensation and GAC filtration have been used in the first three PFAS treatment field demonstrations. It should be noted that PFAS compounds will stick to surfaces and that decontamination of the equipment is important. This could generate additional waste as GAC vessels, pipes and other wetted equipment need careful cleaning with solvents or rinsing agents such as PerfluorAd<sup><small>TM</small></sup>.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==PFAS Reactivity and Fate== | + | ===Oxygen Coil, Overflow Bag and Drip Chamber=== |

| − | While evaluating initial soil treatment results, Crownover ''et al''<ref name="CrownoverEtAl2019"/> noted the lack of complete data sets when the soils were analyzed for non-targeted compounds or extractable precursors. Attempts to establish the fluorine balance suggest that the final fate of the fluorine in the PFAS is not yet fully understood. Transformations are likely occurring in the heated soil as demonstrated in laboratory experiments with and without calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)<small><sub>2</sub></small>) amendment<ref>Koster van Groos, P.G., 2021. Small-Scale Thermal Treatment of Investigation-Derived Wastes Containing PFAS. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/ Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP) - Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP)], [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/2f1577ac-c8ea-4ae8-804e-c9f97a12edb3/small-scale-thermal-treatment-of-investigation-derived-wastes-idw-containing-pfas Project ER18-1556 Website], [[Media: ER18-1556_Final_Report.pdf | Final Report.pdf]]</ref>. Amendments such as Ca(OH)<sub><small>2</small></sub> may be useful in reducing the required treatment temperature by catalyzing PFAS degradation. With thousands of PFAS potentially present, the interactions are complex and may never be fully understood. Therefore, successful thermal treatment may require a higher target temperature than for other organics with similar boiling points – simply to provide a buffer against the uncertainty.

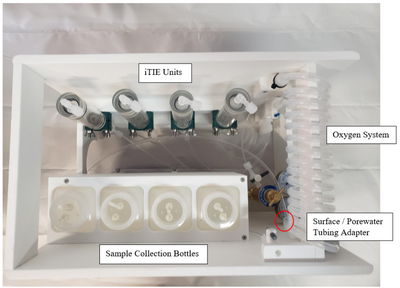

| + | [[File: CraneFig3.png | thumb | left | 400 px | Figure 3. Contents of the iTIE system cooler. The pictured HDPE rack (47.6 cm length x 29.7 cm width x 33.7 cm height) is removable from the iTIE cooler. Water enters the system at the red circle, flows through the oxygen coil, and then travels to each of the individual iTIE units where diagnostic resins and organisms are located. The water then briefly leaves the cooler to travel through peristaltic regulation pumps before being gathered in sample collection bottles.]] |

| | + | Porewater is naturally anoxic due to limited mixing with aerated surface water and high oxygen demand of sediments, which may cause organism mortality and interfere with iTIE results. To preclude this, sampled porewater is exposed to an oxygen coil. This consists of an interior silicone tube connected to a pressurized oxygen canister, threaded through an exterior reinforced PVC tube through which water is slowly pumped (Figure 3). Pump rates are optimized to ensure adequate aeration of the water. In addition to elevating DO levels, the oxygen coil facilitates the oxidation of dissolved sulfides, which naturally occur in some marine sediments and may otherwise cause toxicity to organisms if left in its reduced form. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Case Studies==

| + | Gas bubbles may form in the oxygen coil over the course of a deployment. These can be disruptive, decreasing water sample volumes and posing a danger to sensitive organisms like daphnids. To account for this, the water travels to a drip chamber after exiting the oxygen coil, which allows gas bubbles to be separated and diverted to an overflow system. The sample water then flows to a manifold which divides the flow into different paths to each of the treatment units for fractionation and organism exposure. |

| − | ===Stock-pile Treatment, Eielson AFB, Alaska ([https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/62098505-de86-43b2-bead-ae8018854141 ESTCP project ER20-5198]<ref name="CrownoverEtAl2023">Crownover, E., Heron, G., Pennell, K., Ramsey, B., Rickabaugh, T., Stallings, P., Stauch, L., Woodcock, M., 2023. Ex Situ Thermal Treatment of PFAS-Impacted Soils, [[Media: ER20-5198 Final Report.pdf | Final Report.]] Eielson Air Force Base, Alaska. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/ Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP) - Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP)], [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/62098505-de86-43b2-bead-ae8018854141 Project ER20-5198 Website]</ref>)===

| |

| − | [[File: HeronFig1.png | thumb | 600 px | Figure 1. TCH treatment of a PFAS-laden stockpile at Eielson AFB, Alaska<ref name="CrownoverEtAl2023"/>]]

| |

| − | Since there has been no approved or widely accepted method for treating soils impacted by PFAS, a common practice has been to excavate PFAS-impacted soil and place it in lined stockpiles. Eielson AFB in Alaska is an example where approximately 50 stockpiles were constructed to temporarily store 150,000 cubic yards of soil. One of the stockpiles containing 134 cubic yards of PFAS-impacted soil was heated to 350-450°C over 90 days (Figure 1). Volatilized PFAS was extracted from the soil using vacuum extraction and treated via condensation and filtration by granular activated charcoal. Under field conditions, PFAS concentration reductions from 230 µg/kg to below 0.5 µg/kg were demonstrated for soils that reached 400°C or higher for 7 days. These soils achieved the Alaska soil standards of 3 µg/kg for PFOS and 1.7 µg/kg for PFOA. Cooler soils near the top of the stockpile had remaining PFOS in the range of 0.5-20 µg/kg with an overall average of 4.1 µg/kg. Sampling of all soils heated to 400°C or higher demonstrated that the soils achieved undetectable levels of targeted PFAS (typical reporting limit was 0.5 µg/kg).

| |

| | | | |

| − | ===''In situ'' Vadose Zone Treatment, Beale AFB, California ([https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/94949542-f9f7-419d-8028-8ba318495641/er20-5250-project-overview ESTCP project ER20-5250]<ref name="Iery2024">Iery, R. 2024. In Situ Thermal Treatment of PFAS in the Vadose Zone. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/ Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP) - Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP)], [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/94949542-f9f7-419d-8028-8ba318495641 Project ER20-5250 Website]. [[Media: ER20-5250 Fact Sheet.pdf | Fact Sheet.pdf]]</ref>)=== | + | ===iTIE Units: Fractionation and Organism Exposure Chambers=== |

| − | [[File: HeronFig2.png | thumb | 600 px | Figure 2. ''In situ'' TCH treatment of a PFAS-rich vadose zone hotspot at Beale AFB, California]] | + | [[File: CraneFig4.png | thumb | 300px | Figure 4. A diagram of the iTIE prototype. Water flows upward into each resin chamber through the unit bottom. After being chemically fractionated in the resin chamber, water travels into the organism chamber, where test organisms have been placed. Water is drawn through the units by high-precision peristaltic pumps.]] |

| − | A former fire-training area at Beale AFB had PFAS concentrations as high as 1,970 µg/kg in shallow soils. In situ treatment of a PFAS-rich soil was demonstrated using 16 TCH borings installed in the source area to a depth of 18 ft (Figure 2). Soils which reached the target temperatures were reduced to PFAS concentrations below 1 µg/kg. Perched water which entered in one side of the area delayed heating in that area, and soils which were affected had more modest PFAS concentration reductions. As a lesson learned, future in situ TCH treatments will include provisions for minimizing water entering the treated volume<ref name="Iery2024"/>. It was demonstrated that with proper water management, even highly impacted soils can be treated to near non-detect concentrations (greater than 99% reduction).

| + | At the core of the iTIE system are separate dual-chamber iTIE units, each with a resin fractionation chamber and an organism exposure chamber (Figure 4). Developed by Burton ''et al.''<ref name="BurtonEtAl2020"/>, the iTIE prototype is constructed from acrylic, with rubber O-rings to connect each piece. Each iTIE unit can contain a different diagnostic resin matrix, customizable to remove specific chemical classes from the water. Sampled water flows into each unit through the bottom and is differentially fractionated by the resin matrix as it travels upward. Then it reaches the organism chamber, where test organisms are placed for exposure. The organism chamber inlet and outlet are covered by mesh to prevent the escape of the test organisms. This continuous flow-through design allows practitioners to capture the temporal heterogeneity of ambient water conditions over the duration of an ''in situ'' exposure. Currently, the iTIE system can support four independent iTIE treatment units. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Constructed Pile Treatment, JBER, Alaska ([https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/eb7311db-6233-4c7f-b23a-e003ac1926c5/pfas-treatment-in-soil-using-thermal-conduction-heating ESTCP Project ER23-8369]<ref name="CrownoverHeron2024">Crownover, E., Heron, G., 2024. PFAS Treatment in Soil Using Thermal Conduction Heating. Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) and [https://serdp-estcp.mil/ Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP) - Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP)], [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/eb7311db-6233-4c7f-b23a-e003ac1926c5/pfas-treatment-in-soil-using-thermal-conduction-heating Project ER23-8369 Website]</ref>)===

| + | After being exposed to test organisms, water is collected in sample bottles. The bottles can be pre-loaded with preservation reagents to allow for later chemical analysis. Sample bottles can be composed of polyethylene, glass or other materials depending on the CoC. |

| − | [[File: HeronFig3.png | thumb | 600 px | Figure 3. Treatment of a 2,000 cubic yard soil pile at JBER, Alaska]]

| |

| − | In 2024, a stockpile of 2,000 cubic yards of PFAS-impacted soil was thermally treated at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson (JBER) in Anchorage, Alaska<ref name="CrownoverHeron2024"/>. This ESTCP project was implemented in partnership with DOD’s Defense Innovation Unit (DIU). Three technology demonstrations were conducted at the site where approximately 6,000 cy of PFAS-impacted soil was treated (TCH, smoldering and kiln-style thermal desorption). Figure 3 shows the fully constructed pile used for the TCH demonstration. In August 2024 the soil temperature for the TCH treatment exceeded 400°C in all monitoring locations. At an energy density of 355 kWh/cy, Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation (ADEC) standards and EPA Residential Regional Screening Levels (RSLs) for PFAS in soil were achieved. At JBER, all 30 post-treatment soil samples were near or below detection limits for all targeted PFAS compounds using EPA Method 1633. The composite of all 30 soil samples was below all detection limits for EPA Method 1633. Detection limits ranged from 0.0052 µg/kg to 0.19 µg/kg.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Advantages and Disadvantages== | + | ===Pumping Sub-system=== |

| | + | [[File: CraneFig5.png | thumb | 300px | Figure 5. The iTIE system pumping sub-system. The sub-system consists of: A) a single booster pump, which is directly connected to the water sampling device and feeds water to the rest of the iTIE system, and B) a set of four regulation pumps, which each connect to the outflow of an individual iTIE unit. Each pump set is housed in a waterproof case with self-contained rechargeable battery power. A tablet is mounted inside the lid of the four pump case, which can be used to program and operate all of the pumps when connected to the internet.]] |

| | + | Water movement through the system is driven by a series of high-precision, programmable peristaltic pumps ([https://ecotechmarine.com/ EcoTech Marine]). Each pump set is housed in a Pelican storm travel case. Power is supplied to each pump by internal rechargeable lithium-iron phosphate batteries ([https://www.bioennopower.com/ Bioenno Power]). |

| | | | |

| | + | First, water is supplied to the system by a booster pump (Figure 5A). This pump is situated between the water sampling sub-system and the oxygen coil. The booster pump: 1) facilitates pore water collection, especially from sediments with high fine particle fractions; 2) helps water overcome vertical lifts to travel to the iTIE system; and 3) prevents vacuums from forming in the iTIE system interior, which can accelerate the formation of disruptive gas bubbles in the oxygen coil. The booster pump should be programmed to supply an excess of water to prevent vacuum formation. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Recommendations==

| + | Second, a set of four regulation pumps ensure precise flow rates through each independent iTIE unit (Figure 5B). Each regulation pump pulls water from the top of an iTIE unit and then dispenses that water into a sample bottle for further analysis. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Range Runoff Treatment Technology Components== | + | ==Study Design Considerations== |

| − | Based on the conceptual foundation of previous research into surface water runoff treatment for other contaminants, with a goal to “trap and treat” the target compounds, the following components were selected for inclusion in the technology developed to address range runoff contaminated with energetic compounds.

| + | ===Diagnostic Resin Treatments=== |

| | + | Several commercially available resins have been verified for use in the iTIE system. Investigators can select resins based on stressor classes of interest at each site. Each resin selectively removes a CoC class from site water prior to organism exposure. |

| | + | *[https://www.dupont.com/products/ambersorb560.html DuPont Ambersorb 560] for removal of 1,4-dioxane and other organic chemicals<ref>Woodard, S., Mohr, T., Nickelsen, M.G., 2014. Synthetic media: A promising new treatment technology for 1,4-dioxane. Remediation Journal, 24(4), pp. 27-40. [https://doi.org/10.1002/rem.21402 doi: 10.1002/rem.21402]</ref> |

| | + | *C18 for nonpolar organic chemicals |

| | + | *[https://www.bio-rad.com/en-us Bio-Rad] [https://www.bio-rad.com/en-us/product/chelex-100-resin?ID=6448ab3e-b96a-4162-9124-7b7d2330288e Chelex] for metals |

| | + | *Granular activated carbon for metals, general organic chemicals, sulfide<ref>Lemos, B.R.S., Teixeira, I.F., de Mesquita, J.P., Ribeiro, R.R., Donnici, C.L., Lago, R.M., 2012. Use of modified activated carbon for the oxidation of aqueous sulfide. Carbon, 50(3), pp. 1386-1393. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2011.11.011 doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2011.11.011]</ref> |

| | + | *[https://www.waters.com/nextgen/us/en.html Waters] [https://www.waters.com/nextgen/us/en/search.html?category=Shop&isocode=en_US&keyword=oasis%20hlb&multiselect=true&page=1&rows=12&sort=best-sellers&xcid=ppc-ppc_23916&gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=14746094146&gbraid=0AAAAAD_uR00nhlNwrhhegNh06pBODTgiN&gclid=CjwKCAiAtLvMBhB_EiwA1u6_PsppE0raci2IhvGnAAe5ijciNcetLaGZo5qA3g3r4Z_La7YAPJtzShoC6LoQAvD_BwE Oasis HLB] for general organic chemicals<ref name="SteigmeyerEtAl2017"/> |

| | + | *[https://www.waters.com/nextgen/us/en.html Waters] [https://www.waters.com/nextgen/us/en/search.html?category=All&enableHL=true&isocode=en_US&keyword=Oasis%20WAX%20&multiselect=true&page=1&rows=12&sort=most-relevant Oasis WAX] for PFAS, organic chemicals of mixed polarity<ref>Iannone, A., Carriera, F., Di Fiore, C., Avino, P., 2024. Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substance (PFAS) Analysis in Environmental Matrices: An Overview of the Extraction and Chromatographic Detection Methods. Analytica, 5(2), pp. 187-202. [https://doi.org/10.3390/analytica5020012 doi: 10.3390/analytica5020012] [[Media: IannoneEtAl2024.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> |

| | + | *Zeolite for ammonia, other organic chemicals |

| | | | |

| − | ===Peat===

| + | Resins must be adequately conditioned prior to use. Otherwise, they may inadequately adsorb toxicants or cause stress to organisms. New resins should be tested for efficacy and toxicity before being used in an iTIE system. |

| − | Previous research demonstrated that a peat-based system provided a natural and sustainable sorptive medium for organic explosives such as HMX, RDX, and TNT, allowing much longer residence times than predicted from hydraulic loading alone<ref>Fuller, M.E., Hatzinger, P.B., Rungkamol, D., Schuster, R.L., Steffan, R.J., 2004. Enhancing the attenuation of explosives in surface soils at military facilities: Combined sorption and biodegradation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(2), pp. 313-324. [https://doi.org/10.1897/03-187 doi: 10.1897/03-187]</ref><ref>Fuller, M.E., Lowey, J.M., Schaefer, C.E., Steffan, R.J., 2005. A Peat Moss-Based Technology for Mitigating Residues of the Explosives TNT, RDX, and HMX in Soil. Soil and Sediment Contamination: An International Journal, 14(4), pp. 373-385. [https://doi.org/10.1080/15320380590954097 doi: 10.1080/15320380590954097]</ref><ref name="FullerEtAl2009">Fuller, M.E., Schaefer, C.E., Steffan, R.J., 2009. Evaluation of a peat moss plus soybean oil (PMSO) technology for reducing explosive residue transport to groundwater at military training ranges under field conditions. Chemosphere, 77(8), pp. 1076-1083. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.08.044 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.08.044]</ref><ref>Hatzinger, P.B., Fuller, M.E., Rungkamol, D., Schuster, R.L., Steffan, R.J., 2004. Enhancing the attenuation of explosives in surface soils at military facilities: Sorption-desorption isotherms. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(2), pp. 306-312. [https://doi.org/10.1897/03-186 doi: 10.1897/03-186]</ref><ref name="SchaeferEtAl2005">Schaefer, C.E., Fuller, M.E., Lowey, J.M., Steffan, R.J., 2005. Use of Peat Moss Amended with Soybean Oil for Mitigation of Dissolved Explosive Compounds Leaching into the Subsurface: Insight into Mass Transfer Mechanisms. Environmental Engineering Science, 22(3), pp. 337-349. [https://doi.org/10.1089/ees.2005.22.337 doi: 10.1089/ees.2005.22.337]</ref>. Peat moss represents a bioactive environment for treatment of the target contaminants. While the majority of the microbial reactions are aerobic due to the presence of measurable dissolved oxygen in the bulk solution, anaerobic reactions (including methanogenesis) can occur in microsites within the peat. The peat-based substrate acts not only as a long term electron donor as it degrades but also acts as a strong sorbent. This is important in intermittently loaded systems in which a large initial pulse of MC can be temporarily retarded on the peat matrix and then slowly degraded as they desorb<ref name="FullerEtAl2009"/><ref name="SchaeferEtAl2005"/>. This increased residence time enhances the biotransformation of energetics and promotes the immobilization and further degradation of breakdown products. Abiotic degradation reactions are also likely enhanced by association with the organic-rich peat (e.g., via electron shuttling reactions of [[Wikipedia: Humic substance | humics]])<ref>Roden, E.E., Kappler, A., Bauer, I., Jiang, J., Paul, A., Stoesser, R., Konishi, H., Xu, H., 2010. Extracellular electron transfer through microbial reduction of solid-phase humic substances. Nature Geoscience, 3, pp. 417-421. [https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo870 doi: 10.1038/ngeo870]</ref>.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ===Soybean Oil=== | + | ===Test Organism Species and Life Stages=== |

| − | Modeling has indicated that peat moss amended with crude soybean oil would significantly reduce the flux of dissolved TNT, RDX, and HMX through the vadose zone to groundwater compared to a non-treated soil (see [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/20e2f05c-fd50-4fd3-8451-ba73300c7531 ESTCP ER-200434]). The technology was validated in field soil plots, showing a greater than 500-fold reduction in the flux of dissolved RDX from macroscale Composition B detonation residues compared to a non-treated control plot<ref name="FullerEtAl2009"/>. Laboratory testing and modeling indicated that the addition of soybean oil increased the biotransformation rates of RDX and HMX at least 10-fold compared to rates observed with peat moss alone<ref name="SchaeferEtAl2005"/>. Subsequent experiments also demonstrated the effectiveness of the amended peat moss material for stimulating perchlorate transformation when added to a highly contaminated soil (Fuller et al., unpublished data). These previous findings clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of peat-based materials for mitigating transport of both organic and inorganic energetic compounds through soil to groundwater.

| + | Practitioners can also select different organism species and life stages for use in the iTIE system, depending on site characteristics and study goals. The iTIE system can accommodate various small test organisms, including embryo-stage fish and most macroinvertebrates. The following common toxicity tests can be adapted for application within iTIE systems<ref>U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response, 1994. Catalogue of Standard Toxicity Tests for Ecological Risk Assessment. ECO Update, 2(2), 4 pages. Publication No. 9345.0.05I [https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-09/documents/v2no2.pdf Free Download] [[Media: usepa1994.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. |

| | + | <ul><u>Freshwater acute toxicity:</u></ul> |

| | + | *[[Wikipedia: Daphnia magna | ''Daphnia magna'']] or [[Wikipedia: Daphnia pulex | ''Daphnia pulex'']] 24-, 48-, and 96-hour survival |

| | + | <ul><u>Freshwater chronic toxicity:</u></ul> |

| | + | *[[Wikipedia: Ceriodaphnia dubia | ''Ceriodaphnia dubia'']] 7-day survival and reproduction |

| | + | *''D. magna'' 7-day survival and reproduction |

| | + | *[[Wikipedia: Fathead minnow | ''Pimephales promelas'']] 7-day embryo-larval survival and teratogenicity |

| | + | *[[Wikipedia: Hyalella azteca | ''Hyalella Azteca'']] 10- or 30-day survival and reproduction |

| | + | <ul><u>Marine acute toxicity:</u></ul> |

| | + | *[[Wikipedia: Americamysis bahia | ''Americamysis bahia'']] 24- and 48-hour survival |

| | + | <ul><u>Marine chronic toxicity:</u></ul> |

| | + | *''Americamysis'' survival, growth and fecundity |

| | + | *[[Wikipedia: Topsmelt silverside | ''Atherinops affinis'']] embryo-larval survival and growth |

| | | | |

| − | ===Biochar===

| + | Acute toxicity is quantifiable via organism survival rates immediately following the termination of an iTIE system field deployment. Chronic toxicity can be quantified by continuing to culture and observe test organisms in-lab. Common chronic endpoints include stunted growth, altered development such as teratogenicity in larval fish, decreased reproduction rates, and changes in gene expression. |

| − | Recent reports have highlighted additional materials that, either alone, or in combination with electron donors such as peat moss and soybean oil, may further enhance the sorption and degradation of surface runoff contaminants, including both legacy energetics and [[Wikipedia: Insensitive_munition#Insensitive_high_explosives | insensitive high explosives (IHE)]]. For instance, [[Wikipedia: Biochar | biochar]], a type of black carbon, has been shown to not only sorb a wide range of organic and inorganic contaminants including MCs<ref>Ahmad, M., Rajapaksha, A.U., Lim, J.E., Zhang, M., Bolan, N., Mohan, D., Vithanage, M., Lee, S.S., Ok, Y.S., 2014. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: A review. Chemosphere, 99, pp. 19-33. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.10.071 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.10.071]</ref><ref>Mohan, D., Sarswat, A., Ok, Y.S., Pittman, C.U., 2014. Organic and inorganic contaminants removal from water with biochar, a renewable, low cost and sustainable adsorbent – A critical review. Bioresource Technology, 160, pp. 191-202. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.01.120 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.01.120]</ref><ref>Oh, S.-Y., Seo, Y.-D., Jeong, T.-Y., Kim, S.-D., 2018. Sorption of Nitro Explosives to Polymer/Biomass-Derived Biochar. Journal of Environmental Quality, 47(2), pp. 353-360. [https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2017.09.0357 doi: 10.2134/jeq2017.09.0357]</ref><ref>Xie, T., Reddy, K.R., Wang, C., Yargicoglu, E., Spokas, K., 2015. Characteristics and Applications of Biochar for Environmental Remediation: A Review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 45(9), pp. 939-969. [https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2014.924180 doi: 10.1080/10643389.2014.924180]</ref>, but also to facilitate their degradation<ref>Oh, S.-Y., Cha, D.K., Kim, B.-J., Chiu, P.C., 2002. Effect of adsorption to elemental iron on the transformation of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene and hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine in solution. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 21(7), pp. 1384-1389. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620210708 doi: 10.1002/etc.5620210708]</ref><ref>Ye, J., Chiu, P.C., 2006. Transport of Atomic Hydrogen through Graphite and its Reaction with Azoaromatic Compounds. Environmental Science and Technology, 40(12), pp. 3959-3964. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es060038x doi: 10.1021/es060038x]</ref><ref name="OhChiu2009">Oh, S.-Y., Chiu, P.C., 2009. Graphite- and Soot-Mediated Reduction of 2,4-Dinitrotoluene and Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine. Environmental Science and Technology, 43(18), pp. 6983-6988. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es901433m doi: 10.1021/es901433m]</ref><ref name="OhEtAl2013">Oh, S.-Y., Son, J.-G., Chiu, P.C., 2013. Biochar-mediated reductive transformation of nitro herbicides and explosives. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 32(3), pp. 501-508. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.2087 doi: 10.1002/etc.2087] [[Media: OhEtAl2013.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref><ref name="XuEtAl2010">Xu, W., Dana, K.E., Mitch, W.A., 2010. Black Carbon-Mediated Destruction of Nitroglycerin and RDX by Hydrogen Sulfide. Environmental Science and Technology, 44(16), pp. 6409-6415. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es101307n doi: 10.1021/es101307n]</ref><ref>Xu, W., Pignatello, J.J., Mitch, W.A., 2013. Role of Black Carbon Electrical Conductivity in Mediating Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) Transformation on Carbon Surfaces by Sulfides. Environmental Science and Technology, 47(13), pp. 7129-7136. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es4012367 doi: 10.1021/es4012367]</ref>. Depending on the source biomass and [[Wikipedia: Pyrolysis| pyrolysis]] conditions, biochar can possess a high [[Wikipedia: Specific surface area | specific surface area]] (on the order of several hundred m<small><sup>2</sup></small>/g)<ref>Zhang, J., You, C., 2013. Water Holding Capacity and Absorption Properties of Wood Chars. Energy and Fuels, 27(5), pp. 2643-2648. [https://doi.org/10.1021/ef4000769 doi: 10.1021/ef4000769]</ref><ref>Gray, M., Johnson, M.G., Dragila, M.I., Kleber, M., 2014. Water uptake in biochars: The roles of porosity and hydrophobicity. Biomass and Bioenergy, 61, pp. 196-205. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2013.12.010 doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2013.12.010]</ref> and hence a high sorption capacity. Biochar and other black carbon also exhibit especially high affinity for [[Wikipedia: Nitro compound | nitroaromatic compounds (NACs)]] including TNT and 2,4-dinitrotoluene (DNT)<ref>Sander, M., Pignatello, J.J., 2005. Characterization of Charcoal Adsorption Sites for Aromatic Compounds: Insights Drawn from Single-Solute and Bi-Solute Competitive Experiments. Environmental Science and Technology, 39(6), pp. 1606-1615. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es049135l doi: 10.1021/es049135l]</ref><ref name="ZhuEtAl2005">Zhu, D., Kwon, S., Pignatello, J.J., 2005. Adsorption of Single-Ring Organic Compounds to Wood Charcoals Prepared Under Different Thermochemical Conditions. Environmental Science and Technology 39(11), pp. 3990-3998. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es050129e doi: 10.1021/es050129e]</ref><ref name="ZhuPignatello2005">Zhu, D., Pignatello, J.J., 2005. Characterization of Aromatic Compound Sorptive Interactions with Black Carbon (Charcoal) Assisted by Graphite as a Model. Environmental Science and Technology, 39(7), pp. 2033-2041. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es0491376 doi: 10.1021/es0491376]</ref>. This is due to the strong [[Wikipedia: Pi-interaction | ''π-π'' electron donor-acceptor interactions]] between electron-rich graphitic domains in black carbon and the electron-deficient aromatic ring of the NAC<ref name="ZhuEtAl2005"/><ref name="ZhuPignatello2005"/>. These characteristics make biochar a potentially effective, low cost, and sustainable sorbent for removing MC and other contaminants from surface runoff and retaining them for subsequent degradation ''in situ''.

| |

| | | | |

| − | Furthermore, black carbon such as biochar can promote abiotic and microbial transformation reactions by facilitating electron transfer. That is, biochar is not merely a passive sorbent for contaminants, but also a redox mediator for their degradation. Biochar can promote contaminant degradation through two different mechanisms: electron conduction and electron storage<ref>Sun, T., Levin, B.D.A., Guzman, J.J.L., Enders, A., Muller, D.A., Angenent, L.T., Lehmann, J., 2017. Rapid electron transfer by the carbon matrix in natural pyrogenic carbon. Nature Communications, 8, Article 14873. [https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14873 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14873] [[Media: SunEtAl2017.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref>.

| + | Several gene expression endpoints have been detectable in bioassays following an iTIE system deployment and in-lab culturing period. Steigmeyer ''et al.''<ref name="SteigmeyerEtAl2017"/> were able to detect changes in the expression of two genes in ''D. magna'' after a 24-hour exposure to bisphenol A. In a separate study, Nichols<ref>Nichols, E., 2023. Methods for Identification and Prioritization of Stressors at Impaired Sites. Masters thesis, University of Michigan. University of Michigan Library Deep Blue Documents. [https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/176142/Nichols_Elizabeth_thesis.pdf?sequence=1 Free Download] [[Media: Nichols2023.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> found a significant decline in acetylcholinesterase activity in ''H. azteca'' after a 24-hour exposure to chlorpyrifos. These results indicate a potential to adapt other gene expression bioassays for use in conjunction with iTIE system field exposures to prove stressor-causality linkages. |

| | | | |

| − | First, the microscopic graphitic regions in biochar can adsorb contaminants like NACs strongly, as noted above, and also conduct reducing equivalents such as electrons and atomic hydrogen to the sorbed contaminants, thus promoting their reductive degradation. This catalytic process has been demonstrated for TNT, DNT, RDX, HMX, and [[Wikipedia: Nitroglycerin | nitroglycerin]]<ref>Oh, S.-Y., Cha, D.K., Chiu, P.C., 2002. Graphite-Mediated Reduction of 2,4-Dinitrotoluene with Elemental Iron. Environmental Science and Technology, 36(10), pp. 2178-2184. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es011474g doi: 10.1021/es011474g]</ref><ref>Oh, S.-Y., Cha, D.K., Kim, B.J., Chiu, P.C., 2004. Reduction of Nitroglycerin with Elemental Iron: Pathway, Kinetics, and Mechanisms. Environmental Science and Technology, 38(13), pp. 3723-3730. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es0354667 doi: 10.1021/es0354667]</ref><ref>Oh, S.-Y., Cha, D.K., Kim, B.J., Chiu, P.C., 2005. Reductive transformation of hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine, octahydro-1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazocine, and methylenedinitramine with elemental iron. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 24(11), pp. 2812-2819. [https://doi.org/10.1897/04-662R.1 doi: 10.1897/04-662R.1]</ref><ref name="OhChiu2009"/><ref name="XuEtAl2010"/> and is expected to occur also for IHE including DNAN and NTO.

| + | ===Cost Effectiveness Study=== |

| | + | Burton ''et al.''<ref name="BurtonEtAl2020"/> conducted a cost effectiveness study comparing the iTIE technology with the traditional US EPA Phase 1 TIE method. Comparisons were based on the estimated time required to complete various sub-tasks within each method. Sub-tasks included organism care, equipment preparation, mobilization and deployment, test maintenance, test termination, demobilization, and test termination analyses. It was ultimately estimated that the iTIE protocol requires 47% less time (67 fewer hours) to complete than the Phase 1 TIE method, with the largest time differences in equipment preparation, deployment, test maintenance, and demobilization. It is important to note that the iTIE method may require additional initial costs for equipment and training. |

| | | | |

| − | Second, biochar contains in its structure abundant redox-facile functional groups such as [[Wikipedia: Quinone | quinones]] and [[Wikipedia: Hydroquinone | hydroquinones]], which are known to accept and donate electrons reversibly. Depending on the biomass and pyrolysis temperature, certain biochar can possess a rechargeable electron storage capacity (i.e., reversible electron accepting and donating capacity) on the order of several millimoles e<small><sup>–</sup></small>/g<ref>Klüpfel, L., Keiluweit, M., Kleber, M., Sander, M., 2014. Redox Properties of Plant Biomass-Derived Black Carbon (Biochar). Environmental Science and Technology, 48(10), pp. 5601-5611. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es500906d doi: 10.1021/es500906d]</ref><ref>Prévoteau, A., Ronsse, F., Cid, I., Boeckx, P., Rabaey, K., 2016. The electron donating capacity of biochar is dramatically underestimated. Scientific Reports, 6, Article 32870. [https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32870 doi: 10.1038/srep32870] [[Media: PrevoteauEtAl2016.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref><ref>Xin, D., Xian, M., Chiu, P.C., 2018. Chemical methods for determining the electron storage capacity of black carbon. MethodsX, 5, pp. 1515-1520. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2018.11.007 doi: 10.1016/j.mex.2018.11.007] [[Media: XinEtAl2018.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref>. This means that when "charged", biochar can provide electrons for either abiotic or biotic degradation of reducible compounds such as MC. The abiotic reduction of DNT and RDX mediated by biochar has been demonstrated<ref name="OhEtAl2013"/> and similar reactions are expected to occur for DNAN and NTO as well. Recent studies have shown that the electron storage capacity of biochar is also accessible to microbes. For example, soil bacteria such as [[Wikipedia: Geobacter | ''Geobacter'']] and [[Wikipedia: Shewanella | ''Shewanella'']] species can utilize oxidized (or "discharged") biochar as an electron acceptor for the oxidation of organic substrates such as lactate and acetate<ref>Kappler, A., Wuestner, M.L., Ruecker, A., Harter, J., Halama, M., Behrens, S., 2014. Biochar as an Electron Shuttle between Bacteria and Fe(III) Minerals. Environmental Science and Technology Letters, 1(8), pp. 339-344. [https://doi.org/10.1021/ez5002209 doi: 10.1021/ez5002209]</ref><ref name="SaquingEtAl2016">Saquing, J.M., Yu, Y.-H., Chiu, P.C., 2016. Wood-Derived Black Carbon (Biochar) as a Microbial Electron Donor and Acceptor. Environmental Science and Technology Letters, 3(2), pp. 62-66. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.5b00354 doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.5b00354]</ref> and reduced (or "charged") biochar as an electron donor for the reduction of nitrate<ref name="SaquingEtAl2016"/>. This is significant because, through microbial access of stored electrons in biochar, contaminants that do not sorb strongly to biochar can still be degraded.

| + | ==Field Application== |

| | + | [[File: CraneFig6.png | thumb | left | 400px | Figure 6. iTIES deployment at the Rouge River, Detroit, MI. In the foreground is the iTIE Cooler Sub-System, which contains iTIE resin treatments and test organism groups, as well as the oxygenation coil and sample collection bottles. Next to the iTIE Cooler are the two pump cases. The Trident can be seen above the pump cases, installed in the river channel near shore.]] |

| | + | The iTIE system has been successfully deployed at a variety of marine and freshwater sites during the proof-of-concept phase of prototype development. One example is the 2024 iTIE system deployment completed near the mouth of the Rouge River in Detroit, MI (Figure 6). The Rouge River watershed has a long history of industrialization, with a legacy of chemical dumping, channelization, damming, and urban runoff<ref>Ridgway, J., Cave, K., DeMaria, A., O’Meara, J., Hartig, J. H., 2018. The Rouge River Area of Concern—A multi-year, multi-level successful approach to restoration of Impaired Beneficial Uses. Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management, 21(4), pp. 398-408. [https://doi.org/10.1080/14634988.2018.1528816 doi: 10.1080/14634988.2018.1528816]</ref>. This has led to degraded environmental conditions, with previous detections of a wide range of chemicals including heavy metals and various organics. |

| | | | |

| − | Similar to nitrate, perchlorate and other relatively water-soluble energetic compounds (e.g., NTO and NQ) may also be similarly transformed using reduced biochar as an electron donor. Unlike other electron donors, biochar can be recharged through biodegradation of organic substrates<ref name="SaquingEtAl2016"/> and thus can serve as a long-lasting sorbent and electron repository in soil. Similar to peat moss, the high porosity and surface area of biochar not only facilitate contaminant sorption but also create anaerobic reducing microenvironments in its inner pores, where reductive degradation of energetic compounds can take place.

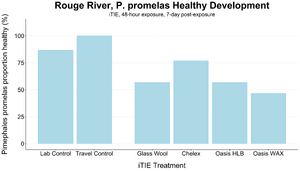

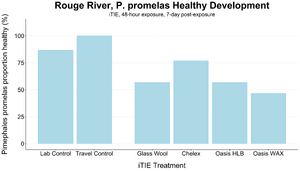

| + | [[File: CraneFig7.png | thumb | 300px | Figure 7. Survival and healthy development of ''P. promelas'' embryos and larvae following a 48-hour iTIE exposure near the mouth of the Rouge River. Organisms were exposed to site porewater as embryos for 48 hours and cultured post-exposure for an additional 5 days.]] |

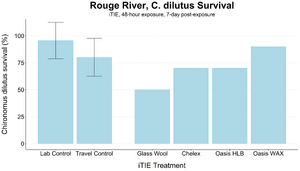

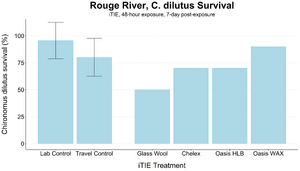

| | + | [[File: CraneFig8.png | thumb | 300px | Figure 8. Survival of ''C. dilutus'' larvae after an iTIE exposure near the mouth of the Rouge River. Organisms were exposed to site porewater for 48 hours and cultured post-exposure for an additional 5 days. Error bars show standard deviation.]] |

| | + | An iTIE system deployment was designed and completed to determine which chemical classes are most responsible for causing toxicity at the site. Resin treatments included glass wool (inert, non-fractionating substance), Chelex (metals sorption), Oasis HLB (general organics sorption), and Oasis WAX (organics sorption, with a high affinity for PFAS). The study utilized fathead minnow (''P. promelas'') embryos, due to their relative sensitivity to metals and PAHs, as well as second-instar midge ([[Wikipedia: Chironomus |''Chironomus dilutus'']]) larvae due to their relative sensitivity to PFAS. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Other Sorbents===

| + | The test organisms were exposed to fractionated porewater ''in situ'' for 48 hours. Following exposure, organisms were cultured for an additional five days, and survival was recorded (Figures 7 and 8). Moderate declines in survival were seen in both species in the glass wool treatment, indicating toxicity at the site. For ''P. promelas'', the highest proportion of healthy development occurred in the Chelex treatment, supporting the hypothesis that metals are a dominant cause of toxicity. ''C. dilutus'' had the greatest survival in the Oasis WAX treatment, suggesting that an organic stressor class like PFAS is also present at harmful concentrations in the river. |

| − | Chitin and unmodified cellulose were predicted by [[Wikipedia: Density functional theory | Density Functional Theory]] methods to be favorable for absorption of NTO and NQ, as well as the legacy explosives<ref>Todde, G., Jha, S.K., Subramanian, G., Shukla, M.K., 2018. Adsorption of TNT, DNAN, NTO, FOX7, and NQ onto Cellulose, Chitin, and Cellulose Triacetate. Insights from Density Functional Theory Calculations. Surface Science, 668, pp. 54-60. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susc.2017.10.004 doi: 10.1016/j.susc.2017.10.004] [[Media: ToddeEtAl2018.pdf | Open Access Manuscript.pdf]]</ref>. Cationized cellulosic materials (e.g., cotton, wood shavings) have been shown to effectively remove negatively charged energetics like perchlorate and NTO from solution<ref name="FullerEtAl2022">Fuller, M.E., Farquharson, E.M., Hedman, P.C., Chiu, P., 2022. Removal of munition constituents in stormwater runoff: Screening of native and cationized cellulosic sorbents for removal of insensitive munition constituents NTO, DNAN, and NQ, and legacy munition constituents HMX, RDX, TNT, and perchlorate. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 424(C), Article 127335. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127335 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127335] [[Media: FullerEtAl2022.pdf | Open Access Manuscript.pdf]]</ref>. A substantial body of work has shown that modified cellulosic biopolymers can also be effective sorbents for removing metals from solution<ref>Burba, P., Willmer, P.G., 1983. Cellulose: a biopolymeric sorbent for heavy-metal traces in waters. Talanta, 30(5), pp. 381-383. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0039-9140(83)80087-3 doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(83)80087-3]</ref><ref>Brown, P.A., Gill, S.A., Allen, S.J., 2000. Metal removal from wastewater using peat. Water Research, 34(16), pp. 3907-3916. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00152-4 doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00152-4]</ref><ref>O’Connell, D.W., Birkinshaw, C., O’Dwyer, T.F., 2008. Heavy metal adsorbents prepared from the modification of cellulose: A review. Bioresource Technology, 99(15), pp. 6709-6724. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2008.01.036 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.01.036]</ref><ref>Wan Ngah, W.S., Hanafiah, M.A.K.M., 2008. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater by chemically modified plant wastes as adsorbents: A review. Bioresource Technology, 99(10), pp. 3935-3948. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2007.06.011 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.06.011]</ref> and therefore will also likely be applicable for some of the metals that may be found in surface runoff at firing ranges.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Technology Evaluation==

| + | Water chemical analyses of fractionated and unfractionated water samples were completed to support biological results. Analyses were conducted for a range of stressor classes including metals, PAHs, PCBs, an organophosphate pesticide (chlorpyrifos), a PFAS compound (PFOS) and a pyrethroid insecticide (permethrin). Of these analytes, only heavy metals and PFOS were detected. Some chemical classes including PAHs and PCBs were not detected at the site. |

| − | Based on the properties of the target munition constituents, a combination of materials was expected to yield the best results to facilitate the sorption and subsequent biotic and abiotic degradation of the contaminants.

| + | To reach similar conclusions using traditional Phase 1 TIE methods, one would need to complete the following tests: baseline toxicity, filtration, aeration, EDTA, C18 SPE, and methanol elution of C18 SPE. The iTIE method allows the same conclusions to be drawn with significantly less time and effort required. |

| − | | |

| − | ===Sorbents===

| |

| − | {| class="wikitable" style="margin-right: 30px; margin-left: auto; float:left; text-align:center;"

| |

| − | |+Table 1. [[Wikipedia: Freundlich equation | Freundlich]] and [[Wikipedia: Langmuir adsorption model | Langmuir]] adsorption parameters for insensitive and legacy explosives

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! rowspan="2" | Compound

| |

| − | ! colspan="5" | Freundlich

| |

| − | ! colspan="5" | Langmuir

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! <small>Parameter</small> !! Peat !! <small>CAT</small> Pine !! <small>CAT</small> Burlap !! <small>CAT</small> Cotton !! <small>Parameter</small> !! Peat !! <small>CAT</small> Pine !! <small>CAT</small> Burlap !! <small>CAT</small> Cotton

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="12" style="background-color:white;" |

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! rowspan="3" | HMX

| |

| − | ! ''K<sub>f</sub>''

| |

| − | | 0.08 +/- 0.00 || -- || -- || --

| |

| − | ! ''q<sub>m</sub>'' <small>(mg/g)</small>

| |

| − | | 0.29 +/- 0.04 || -- || -- || --

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! ''n''

| |

| − | | 1.70 +/- 0.18 || -- || -- || --

| |

| − | ! ''b'' <small>(L/mg)</small>

| |

| − | | 0.39 +/- 0.09 || -- || -- || --

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>''

| |

| − | | 0.91 || -- || -- || --

| |

| − | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>''

| |

| − | | 0.93 || -- || -- || --

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="12" style="background-color:white;" |

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! rowspan="3" | RDX

| |

| − | ! ''K<sub>f</sub>''

| |

| − | | 0.11 +/- 0.02 || -- || -- || --

| |

| − | ! ''q<sub>m</sub>'' <small>(mg/g)</small>

| |

| − | | 0.38 +/- 0.05 || -- || -- || --

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! ''n''

| |

| − | | 2.75 +/- 0.63 || -- || -- || --

| |

| − | ! ''b'' <small>(L/mg)</small>

| |

| − | | 0.23 +/- 0.08 || -- || -- || --

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>''

| |

| − | | 0.69 || -- || -- || --

| |

| − | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>''

| |

| − | | 0.69 || -- || -- || --

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="12" style="background-color:white;" |

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! rowspan="3" | TNT

| |

| − | ! ''K<sub>f</sub>''

| |

| − | | 1.21 +/- 0.15 || 1.02 +/- 0.04 || 0.36 +/- 0.02 || --

| |

| − | ! ''q<sub>m</sub>'' <small>(mg/g)</small>

| |

| − | | 3.63 +/- 0.18 || 1.26 +/- 0.06 || -- || --

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! ''n''

| |

| − | | 2.78 +/- 0.67 || 4.01 +/- 0.44 || 1.59 +/- 0.09 || --

| |

| − | ! ''b'' <small>(L/mg)</small>

| |

| − | | 0.89 +/- 0.13 || 0.76 +/- 0.10 || -- || --

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>''

| |

| − | | 0.81 || 0.93 || 0.98 || --

| |

| − | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>''

| |

| − | | 0.97 || 0.97 || -- || --

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="12" style="background-color:white;" |

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! rowspan="3" | NTO

| |

| − | ! ''K<sub>f</sub>''

| |

| − | | -- || 0.94 +/- 0.05 || 0.41 +/- 0.05 || 0.26 +/- 0.06

| |

| − | ! ''q<sub>m</sub>'' <small>(mg/g)</small>

| |

| − | | -- || 4.07 +/- 0.26 || 1.29 +/- 0.12 || 0.83 +/- .015

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! ''n''

| |

| − | | -- || 1.61 +/- 0.11 || 2.43 +/- 0.41 || 2.53 +/- 0.76

| |

| − | ! ''b'' <small>(L/mg)</small>

| |

| − | | -- || 0.30 +/- 0.04 || 0.36 +/- 0.08 || 0.30 +/- 0.15

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>''

| |

| − | | -- || 0.97 || 0.82 || 0.57

| |

| − | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>''

| |

| − | | -- || 0.99 || 0.89 || 0.58

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="12" style="background-color:white;" |

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! rowspan="3" | DNAN

| |

| − | ! ''K<sub>f</sub>''

| |

| − | | 0.38 +/- 0.05 || 0.01 +/- 0.01 || -- || --

| |

| − | ! ''q<sub>m</sub>'' <small>(mg/g)</small>

| |

| − | | 2.57 +/- 0.33 || -- || -- || --

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! ''n''

| |

| − | | 1.71 +/- 0.20 || 0.70 +/- 0.13 || -- || --

| |

| − | ! ''b'' <small>(L/mg)</small>

| |

| − | | 0.13 +/- 0.03 || -- || -- || --

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>''

| |

| − | | 0.89 || 0.76 || -- || --

| |

| − | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>''

| |

| − | | 0.92 || -- || -- || --

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="12" style="background-color:white;" |

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! rowspan="3" | ClO<sub>4</sup>

| |

| − | ! ''K<sub>f</sub>''

| |

| − | | -- || 1.54 +/- 0.06 || 0.53 +/- 0.03 || --

| |

| − | ! ''q<sub>m</sub>'' <small>(mg/g)</small>

| |

| − | | -- || 3.63 +/- 0.18 || 1.26 +/- 0.06 || --

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! ''n''

| |

| − | | -- || 2.42 +/- 0.16 || 2.42 +/- 0.26 || --

| |

| − | ! ''b'' <small>(L/mg)</small>

| |

| − | | -- || 0.89 +/- 0.13 || 0.76 +/- 0.10 || --

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>''

| |

| − | | -- || 0.97 || 0.92 || --

| |

| − | ! ''r<sup><small>2</small></sup>''

| |

| − | | -- || 0.97 || 0.97 || --

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="12" style="text-align:left; background-color:white;" |<small>Notes:</small><br /><big>'''--'''</big> <small>Indicates the algorithm failed to converge on the model fitting parameters, therefore there was no successful model fit.<br />'''CAT''' Indicates cationized material.</small>

| |

| − | |}

| |

| − | | |

| − | The materials screened included [[Wikipedia: Sphagnum | ''Sphagnum'' peat moss]], primarily for sorption of HMX, RDX, TNT, and DNAN, as well as [[Wikipedia: Cationization of cotton | cationized cellulosics]] for removal of perchlorate and NTO. The cationized cellulosics that were examined included: pine sawdust, pine shavings, aspen shavings, cotton linters (fine, silky fibers which adhere to cotton seeds after ginning), [[Wikipedia: Chitin | chitin]], [[Wikipedia: Chitosan | chitosan]], burlap (landscaping grade), [[Wikipedia: Coir | coconut coir]], raw cotton, raw organic cotton, cleaned raw cotton, cotton fabric, and commercially cationized fabrics.

| |

| − | | |

| − | As shown in Table 1<ref name="FullerEtAl2022"/>, batch sorption testing indicated that a combination of Sphagnum peat moss and cationized pine shavings provided good removal of both the neutral organic energetics (HMX, RDX, TNT, DNAN) as well as the negatively charged energetics (perchlorate, NTO).

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Slow Release Carbon Sources===

| |

| − | {| class="wikitable" style="margin-right: 30px; margin-left: auto; float:left; text-align:center;"

| |

| − | |+Table 2. Slow-release Carbon Sources

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | ! Material !! Abbreviation !! Commercial Source !! Notes

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | polylactic acid || PLA6 || [https://www.goodfellow.com/usa?srsltid=AfmBOoqEiqIbrvWb1Hn1Bc090efBUUfg6V4N3Vrn6ytajHMJR-FG1Ez- Goodfellow] || high molecular weight thermoplastic polyester

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | polylactic acid || PLA80 || [https://www.goodfellow.com/usa?srsltid=AfmBOoqEiqIbrvWb1Hn1Bc090efBUUfg6V4N3Vrn6ytajHMJR-FG1Ez- Goodfellow] || low molecular weight thermoplastic polyester

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | polyhydroxybutyrate || PHB || [https://www.goodfellow.com/usa?srsltid=AfmBOoqEiqIbrvWb1Hn1Bc090efBUUfg6V4N3Vrn6ytajHMJR-FG1Ez- Goodfellow] || bacterial polyester

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | polycaprolactone || PCL || [https://www.sarchemlabs.com/?hsa_acc=4540346154&hsa_cam=20281343997&hsa_grp&hsa_ad&hsa_src=x&hsa_tgt&hsa_kw&hsa_mt&hsa_net=adwords&hsa_ver=3&gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=21209931835 Sarchem Labs] || biodegradable polyester

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | polybutylene succinate || BioPBS || [https://us.mitsubishi-chemical.com/company/performance-polymers/ Mitsubishi Chemical Performance Polymers] || compostable bio-based product

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | sucrose ester of fatty acids || SEFA SP10 || [https://www.sisterna.com/ Sisterna] || food and cosmetics additive

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | sucrose ester of fatty acids || SEFA SP70 || [https://www.sisterna.com/ Sisterna] || food and cosmetics additive

| |

| − | |}

| |

| − | | |

| − | A range of biopolymers widely used in the production of biodegradable plastics were screened for their ability to support aerobic and anoxic biodegradation of the target munition constituents. These compounds and their sources are listed in Table 2.

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[File: FullerFig3.png | thumb | 400 px | Figure 3. Schematic of interactions between biochar and munitions constituents]]

| |

| − | Multiple pure bacterial strains and mixed cultures were screened for their ability to utilize the solid biopolymers as a carbon source to support energetic compound transformation and degradation. Pure strains included the aerobic RDX degrader [[Wikipedia: Rhodococcus | ''Rhodococcus'']] species DN22 (DN22 henceforth)<ref name="ColemanEtAl1998">Coleman, N.V., Nelson, D.R., Duxbury, T., 1998. Aerobic biodegradation of hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) as a nitrogen source by a Rhodococcus sp., strain DN22. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 30(8-9), pp. 1159-1167. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-0717(97)00172-7 doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(97)00172-7]</ref> and [[Wikipedia: Gordonia (bacterium)|''Gordonia'']] species KTR9 (KTR9 henceforth)<ref name="ColemanEtAl1998"/>, the anoxic RDX degrader [[Wikipedia: Pseudomonas fluorencens | ''Pseudomonas fluorencens'']] species I-C (I-C henceforth)<ref>Pak, J.W., Knoke, K.L., Noguera, D.R., Fox, B.G., Chambliss, G.H., 2000. Transformation of 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene by Purified Xenobiotic Reductase B from Pseudomonas fluorescens I-C. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 66(11), pp. 4742-4750. [https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.66.11.4742-4750.2000 doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.11.4742-4750.2000] [[Media: PakEtAl2000.pdf | Open AccessArticle.pdf]]</ref><ref>Fuller, M.E., McClay, K., Hawari, J., Paquet, L., Malone, T.E., Fox, B.G., Steffan, R.J., 2009. Transformation of RDX and other energetic compounds by xenobiotic reductases XenA and XenB. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 84, pp. 535-544. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-009-2024-6 doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2024-6] [[Media: FullerEtAl2009.pdf | Open Access Manuscript]]</ref>, and the aerobic NQ degrader [[Wikipedia: Pseudomonas | ''Pseudomonas extremaustralis'']] species NQ5 (NQ5 henceforth)<ref>Kim, J., Fuller, M.E., Hatzinger, P.B., Chu, K.-H., 2024. Isolation and characterization of nitroguanidine-degrading microorganisms. Science of the Total Environment, 912, Article 169184. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169184 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169184]</ref>. Anaerobic mixed cultures were obtained from a membrane bioreactor (MBR) degrading a mixture of six explosives (HMX, RDX, TNT, NTO, NQ, DNAN), as well as perchlorate and nitrate<ref name="FullerEtAl2023">Fuller, M.E., Hedman, P.C., Chu, K.-H., Webster, T.S., Hatzinger, P.B., 2023. Evaluation of a sequential anaerobic-aerobic membrane bioreactor system for treatment of traditional and insensitive munitions constituents. Chemosphere, 340, Article 139887. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.139887 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.139887]</ref>. The results indicated that the slow-release carbon sources [[Wikipedia: Polyhydroxybutyrate | polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB)]], [[Wikipedia: Polycaprolactone | polycaprolactone (PCL)]], and [[Wikipedia: Polybutylene succinate | polybutylene succinate (BioPBS)]] were effective for supporting the biodegradation of the mixture of energetics.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Biochar===

| |

| − | [[File: FullerFig4.png | thumb | left | 500 px | Figure 4. Composition of the columns during the sorption-biodegradation experiments]]

| |

| − | [[File: FullerFig5.png | thumb | 500 px | Figure 5. Representative breakthrough curves of energetics during the second replication of the column sorption-biodegradation experiment]]

| |

| − | The ability of biochar to sorb and abiotically reduce legacy and insensitive munition constituents, as well as biochar’s use as an electron donor for microbial biodegradation of energetic compounds was examined. Batch experiments indicated that biochar was a reasonable sorbent for some of the energetics (RDX, DNAN), but could also serve as both an electron acceptor and an electron donor to facilitate abiotic (RDX, DNAN, NTO) and biotic (perchlorate) degradation (Figure 3)<ref>Xin, D., Giron, J., Fuller, M.E., Chiu, P.C., 2022. Abiotic reduction of 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO), DNAN, and RDX by wood-derived biochars through their rechargeable electron storage capacity. Environmental Science: Processes and Impacts, 24(2), pp. 316-329. [https://doi.org/10.1039/D1EM00447F doi: 10.1039/D1EM00447F] [[Media: XinEtAl2022.pdf | Open Access Manuscript.pdf]]</ref>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Sorption-Biodegradation Column Experiments===

| |

| − | The selected materials and cultures discussed above, along with a small amount of range soil and crushed oyster shell as a slow-release pH buffering agent, were packed into columns, and a steady flow of dissolved energetics was passed through the columns. The composition of the four columns is presented in Figure 4. The influent and effluent concentrations of the energetics was monitored over time. The column experiment was performed twice. As seen in Figure 5, there was sustained almost complete removal of RDX and ClO<sub>4</sub><sup>-</sup>, and more removal of the other energetics in the bioactive columns compared to the sorption only columns, over the course of the experiments. For reference, 100 PV is approximately equivalent to three months of operation. The higher effectiveness of sorption with biodegradation compared to sorption only is further illustrated in Figure 6, where the energetics mass removal in the bioactive columns was shown to be 2-fold (TNT) to 20-fold (RDX) higher relative to that observed in the sorption only column. The mass removal of HMX and NQ were both over 40% higher with biochar added to the sorption with biodegradation treatment, although biochar showed little added benefit for removal of other energetics tested.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Trap and Treat Technology===

| |

| − | [[File: FullerFig6.png | thumb | left | 400 px | Figure 6. Energetic mass removal relative to the sorption only removal during the column sorption-biodegradation experiments. Dashed line given for reference to C1 removal = 1.]]

| |

| − | These results provide a proof-of-concept for the further development of a passive and sustainable “trap-and-treat” technology for remediation of energetic compounds in stormwater runoff at military testing and training ranges. At a given site, the stormwater runoff would need to be fully characterized with respect to key parameters (e.g., pH, major anions), and site specific treatability testing would be recommended to assure there was nothing present in the runoff that would reduce performance. Effluent monitoring on a regular basis would also be needed (and would be likely be expected by state and local regulators) to assess performance decline over time.

| |

| − | | |

| − | The components of the technology would be predominantly peat moss and cationized pine shavings, supplemented with biochar, ground oyster shell, the biopolymer carbon sources, and the bioaugmentation cultures. The entire mix would likely be emplaced in a concrete vault at the outflow end of the stormwater runoff retention basin at the contaminated site. The deployed treatment system would have further design elements, such as a system to trap and retain suspended solids in the runoff in order to minimize clogging the matrix. the inside of the vault would be baffled to maximize the hydraulic retention time of the contaminated runoff. The biopolymer carbon sources and oyster shell may need be refreshed periodically (perhaps yearly) to maintain performance. However, a complete removal and replacement of the base media (peat moss, CAT pine) would not be advised, as that would lead to a loss of the acclimated biomass.

| |

| | | | |

| | ==Summary== | | ==Summary== |

| − | Novel sorbents and slow-release carbon sources can be an effective way to promote the sorption and biodegradation of a range of legacy and insensitive munition constituents from surface runoff, and the added benefits of biochar for both sorption and biotic and abiotic degradation of these compounds was demonstrated. These results establish a foundation for a passive, sustainable surface runoff treatment technology for both active and inactive military ranges.

| + | The ''in situ'' Toxicity Identification Evaluation technology and protocol is a powerful tool that investigators can use to strengthen causal linkages between chemical stressors and ecological toxicity. By fractionating sampled water and exposing test organisms ''in situ'', investigators can gather toxicity response data while minimizing sample manipulation and accurately representing environmental conditions. |

| | + | <br clear="right"/> |

| | | | |