Difference between revisions of "User:Jhurley/sandbox"

(→System Components and Validation) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | == | + | ==''In Situ'' Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE)== |

| − | + | The ''in situ'' Toxicity Identification Evaluation system is a tool to incorporate into weight-of-evidence studies at sites with numerous chemical toxicant classes present. The technology works by continuously sampling site water, immediately fractionating the water using diagnostic sorptive resins, and then exposing test organisms to the water to observe toxicity responses with minimal sample manipulation. It is compatible with various resins, test organisms, and common acute and chronic toxicity tests, and can be deployed at sites with a wide variety of physical and logistical considerations. | |

<div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | ||

'''Related Article(s):''' | '''Related Article(s):''' | ||

| − | * [[ | + | *[[Contaminated Sediments - Introduction]] |

| − | * [[ | + | *[[Contaminated Sediment Risk Assessment]] |

| − | ''' | + | '''Contributors:''' Dr. G. Allen Burton Jr., Austin Crane |

| − | '''Key | + | '''Key Resources:''' |

| + | *A Novel In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) System for Determining which Chemicals Drive Impairments at Contaminated Sites<ref name="BurtonEtAl2020">Burton, G.A., Cervi, E.C., Meyer, K., Steigmeyer, A., Verhamme, E., Daley, J., Hudson, M., Colvin, M., Rosen, G., 2020. A novel In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) System for Determining which Chemicals Drive Impairments at Contaminated Sites. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 39(9), pp. 1746-1754. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.4799 doi: 10.1002/etc.4799]</ref> | ||

| + | *An in situ toxicity identification and evaluation water analysis system: Laboratory validation<ref name="SteigmeyerEtAl2017">Steigmeyer, A.J., Zhang, J., Daley, J.M., Zhang, X., Burton, G.A. Jr., 2017. An in situ toxicity identification and evaluation water analysis system: Laboratory validation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 36(6), pp. 1636-1643. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.3696 doi: 10.1002/etc.3696]</ref> | ||

| + | *Sediment Toxicity Identification Evaluation (TIE) Phases I, II, and III Guidance Document- <ref>United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2007. Sediment Toxicity Identification Evaluation (TIE) Phases I, II, and III Guidance Document, EPA/600/R-07/080. 145 pages. [https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPURL.cgi?Dockey=P1003GR1.txt Free Download] [[Media: EPA2007.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> | ||

| + | *In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) Technology for Assessing Contaminated Sediments, Remediation Success, Recontamination and Source Identification- <ref>In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) Technology for Assessing Contaminated Sediments, Remediation Success, Recontamination and Source Identification [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/88a8f9ba-542b-4b98-bfa4-f693435535cd/er18-1181-project-overview Project Website] [[Media: ER18-1181Ph.II.pdf | Final Report.pdf]]</ref> | ||

| − | + | ==Introduction== | |

| + | In waterways impacted by numerous naturally occurring and anthropogenic chemical stressors, it is crucial for environmental practitioners to be able to identify which chemical classes are causing the highest degrees of toxicity to aquatic life. Previously developed methods, including the Toxicity Identification Evaluation (TIE) protocol developed by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)<ref>Norberg-King, T., Mount, D.I., Amato, J.R., Jensen, D.A., Thompson, J.A., 1992. Toxicity identification evaluation: Characterization of chronically toxic effluents: Phase I. Publication No. EPA/600/6-91/005F. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development. [https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-09/documents/owm0255.pdf Free Download from US EPA] [[Media: usepa1992.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>, can be confounded by sample manipulation artifacts and temporal limitations of ''ex situ'' organism exposures<ref name="BurtonEtAl2020"/>. These factors may disrupt causal linkages and mislead investigators during site characterization and management decision-making. The ''in situ'' Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) technology was developed to allow users to strengthen stressor-causality linkages and rank chemical classes of concern at impaired sites, with high degrees of ecological realism. | ||

| − | + | The technology has undergone a series of improvements in recent years, with the most recent prototype being robust, operable in a wide variety of site conditions, and cost-effective compared to alternative site characterization methods<ref>Burton, G.A. Jr., Nordstrom, J.F., 2004. An in situ toxicity identification evaluation method part I: Laboratory validation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(12), pp. 2844-2850. [https://doi.org/10.1897/03-409.1 doi: 10.1897/03-409.1]</ref><ref>Burton, G.A. Jr., Nordstrom, J.F., 2004. An in situ toxicity identification evaluation method part II: Field validation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(12), pp. 2851-2855. [https://doi.org/10.1897/03-468.1 doi: 10.1897/03-468.1]</ref><ref name="BurtonEtAl2020"/><ref name="SteigmeyerEtAl2017"/>. The latest prototype can be used in any of the following settings: in marine, estuarine, or freshwater sites; to study surface water or sediment pore water; in shallow waters easily accessible by foot or in deep waters only accessible by pier or boat. It can be used to study sites impacted by a wide variety of stressors including ammonia, [[Metal and Metalloid Contaminants | metals]], pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB), [[Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) | polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH)]], and [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)]], among others. The technology is applicable to studies of acute toxicity via organism survival or of chronic toxicity via responses in growth, reproduction, or gene expression<ref name="BurtonEtAl2020"/>. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==System Components and Validation== | |

| + | The latest iTIE prototype consists of an array of sorptive resins that differentially fractionate sampled water, and a series of corresponding flow-through organism chambers that receive the treated water ''in situ''. Resin treatments can be selected depending on the chemicals suspected to be present at each site to selectively sequester certain chemical of concern (CoC) classes from the whole water, leaving a smaller subset of chemicals in the resulting water fraction for chemical and toxicological characterization. Test organism species and life stages can also be chosen depending on factors including site characteristics and study goals. In the full iTIE protocol, site water is continuously sampled either from the sediment pore spaces or the water column at a site, gently oxygenated, diverted to different iTIE units for fractionation and organism exposure, and collected in sample bottles for off-site chemical analysis (Figure 1). All iTIE system components are housed within waterproof Pelican cases, which allow for ease of transport and temperature control. | ||

| − | [[File: | + | ===Porewater and Surface Water Collection Sub-system=== |

| − | + | [[File: CraneFig1.png | thumb | left | 700 px | Figure 1: A schematic diagram of the iTIE system prototype. The system is divided into three sub-systems: 1) the Pore Water/Surface Water Collection Sub-System (blue); 2) the Pumping Sub-System (red); and 3) the iTIE Resin, Exposure, and Sampling Sub-System (green). Water first enters the system through the Pore Water/Surface Water Collection Sub-System. Porewater can be collected using Trident-style probes, or surface water can be collected using a simple weighted probe. The water is composited in a manifold before being pumped to the rest of the iTIE system by the booster pump. Once in the iTIE Resin, Exposure, and Sampling Sub-System, the water is gently oxygenated by the Oxygen Coil, separated from gas bubbles by the Drip Chamber, and diverted to separate iTIE Resin and Exposure Chambers (or iTIE units) by the Splitting Manifold. Water movement through each iTIE unit is controlled by a dedicated Regulation Pump. Finally, the water is gathered in Sample Collection bottles for analysis.]] | |

| + | [[File: CraneFig2.png | thumb | left | 500 px | Figure 2: a) Trident probe with auxiliary sensors attached, b) a Trident probe with end caps removed (the red arrow identifies the intermediate space where glass beads are packed to filter suspended solids), c) a Trident probe being installed using a series of push poles and a fence post driver]] | ||

| − | + | Given the importance of sediment porewater to ecosystem structure and function, investigators may employ the iTIE system to evaluate the toxic effects associated with the impacted sediment porewater. To accomplish this, the iTIE system utilizes the Trident probe, originally developed for Department of Defense site characterization studies<ref>Chadwick, D.B., Harre, B., Smith, C.F., Groves, J.G., Paulsen, R.J., 2003. Coastal Contaminant Migration Monitoring: The Trident Probe and UltraSeep System. Hardware Description, Protocols, and Procedures. Technical Report 1902. Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center.</ref>. The main body of the Trident is comprised of a stainless-steel frame with six hollow probes (Figure 2). Each probe contains a layer of inert glass beads, which filters suspended solids from the sampled water. The water is drawn through each probe into a composite manifold and transported to the rest of the iTIE system using a high-precision peristaltic pump. | |

| − | + | The Trident also includes an adjustable stopper plate, which forms a seal against the sediment and prevents the inadvertent dilution of porewater samples with surface water. (Figure 2). Preliminary laboratory results indicate that the Trident is extremely effective in collecting porewater samples with minimal surface water infiltration in sediments ranging from coarse sand to fine clay. Underwater cameras, sensors, passive samplers, and other auxiliary equipment can be attached to the Trident probe frame to provide supplemental data. | |

| − | |||

| − | The | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Alternatively, practitioners may employ the iTIE system to evaluate site surface water. To sample surface water, weighted intake tubes can collect surface water from the water column using a peristaltic pump. | |

| − | + | <br clear="left"/> | |

| − | The [[ | + | ==Advantages== |

| + | A UV/sulfite treatment system offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction compared to other technologies, including high defluorination percentage, high treatment efficiency for short-chain PFAS without mass transfer limitation, selective reactivity by ''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'', low energy consumption, and the production of no harmful byproducts. A summary of these advantages is provided below: | ||

| + | *'''High efficiency for short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS:''' While the degradation efficiency for short-chain PFAS is challenging for some treatment technologies<ref>Singh, R.K., Brown, E., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2021. Treatment of PFAS-containing landfill leachate using an enhanced contact plasma reactor. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 408, Article 124452. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452]</ref><ref>Singh, R.K., Multari, N., Nau-Hix, C., Woodard, S., Nickelsen, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2020. Removal of Poly- and Per-Fluorinated Compounds from Ion Exchange Regenerant Still Bottom Samples in a Plasma Reactor. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(21), pp. 13973-80. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c02158 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02158]</ref><ref>Nau-Hix, C., Multari, N., Singh, R.K., Richardson, S., Kulkarni, P., Anderson, R.H., Holsen, T.M., Mededovic Thagard S., 2021. Field Demonstration of a Pilot-Scale Plasma Reactor for the Rapid Removal of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Groundwater. American Chemical Society’s Environmental Science and Technology (ES&T) Water, 1(3), pp. 680-87. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170 doi: 10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170]</ref>, the UV/sulfite process demonstrates excellent defluorination efficiency for both short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS, including [[Wikipedia: Trifluoroacetic acid | trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)]] and [[Wikipedia: Perfluoropropionic acid | perfluoropropionic acid (PFPrA)]]. | ||

| + | *'''High defluorination ratio:''' As shown in Figure 3, the UV/sulfite treatment system has demonstrated near 100% defluorination for various PFAS under both laboratory and field conditions. | ||

| + | *'''No harmful byproducts:''' While some oxidative technologies, such as electrochemical oxidation, generate toxic byproducts, including perchlorate, bromate, and chlorate, the UV/sulfite system employs a reductive mechanism and does not generate these byproducts. | ||

| + | *'''Ambient pressure and low temperature:''' The system operates under ambient pressure and low temperature (<60°C), as it utilizes UV light and common chemicals to degrade PFAS. | ||

| + | *'''Low energy consumption:''' The electrical energy per order values for the degradation of [[Wikipedia: Perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids | perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs)]] by UV/sulfite have been reduced to less than 1.5 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per cubic meter under laboratory conditions. The energy consumption is orders of magnitude lower than that for many other destructive PFAS treatment technologies (e.g., [[Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO) | supercritical water oxidation]])<ref>Nzeribe, B.N., Crimi, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holsen, T.M., 2019. Physico-Chemical Processes for the Treatment of Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): A Review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 49(10), pp. 866-915. [https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2018.1542916 doi: 10.1080/10643389.2018.1542916]</ref>. | ||

| + | *'''Co-contaminant destruction:''' The UV/sulfite system has also been reported effective in destroying certain co-contaminants in wastewater. For example, UV/sulfite is reported to be effective in reductive dechlorination of chlorinated volatile organic compounds, such as trichloroethene, 1,2-dichloroethane, and vinyl chloride<ref>Jung, B., Farzaneh, H., Khodary, A., Abdel-Wahab, A., 2015. Photochemical degradation of trichloroethylene by sulfite-mediated UV irradiation. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 3(3), pp. 2194-2202. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2015.07.026 doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2015.07.026]</ref><ref>Liu, X., Yoon, S., Batchelor, B., Abdel-Wahab, A., 2013. Photochemical degradation of vinyl chloride with an Advanced Reduction Process (ARP) – Effects of reagents and pH. Chemical Engineering Journal, 215-216, pp. 868-875. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2012.11.086 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.11.086]</ref><ref>Li, X., Ma, J., Liu, G., Fang, J., Yue, S., Guan, Y., Chen, L., Liu, X., 2012. Efficient Reductive Dechlorination of Monochloroacetic Acid by Sulfite/UV Process. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(13), pp. 7342-49. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es3008535 doi: 10.1021/es3008535]</ref><ref>Li, X., Fang, J., Liu, G., Zhang, S., Pan, B., Ma, J., 2014. Kinetics and efficiency of the hydrated electron-induced dehalogenation by the sulfite/UV process. Water Research, 62, pp. 220-228. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.051 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.051]</ref>. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Limitations== |

| + | Several environmental factors and potential issues have been identified that may impact the performance of the UV/sulfite treatment system, as listed below. Solutions to address these issues are also proposed. | ||

| + | *Environmental factors, such as the presence of elevated concentrations of natural organic matter (NOM), dissolved oxygen, or nitrate, can inhibit the efficacy of UV/sulfite treatment systems by scavenging available hydrated electrons. Those interferences are commonly managed through chemical additions, reaction optimization, and/or dilution, and are therefore not considered likely to hinder treatment success. | ||

| + | *Coloration in waste streams may also impact the effectiveness of the UV/sulfite treatment system by blocking the transmission of UV light, thus reducing the UV lamp's effective path length. To address this, pre-treatment may be necessary to enable UV/sulfite destruction of PFAS in the waste stream. Pre-treatment may include the use of strong oxidants or coagulants to consume or remove UV-absorbing constituents. | ||

| + | *The degradation efficiency is strongly influenced by PFAS molecular structure, with fluorotelomer sulfonates (FTS) and [[Wikipedia: Perfluorobutanesulfonic acid | perfluorobutanesulfonate (PFBS)]] exhibiting greater resistance to degradation by UV/sulfite treatment compared to other PFAS compounds. | ||

| − | + | ==State of the Practice== | |

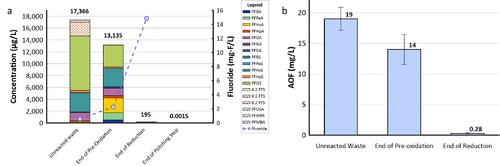

| − | + | [[File: XiongFig2.png | thumb | 500 px | Figure 2. Field demonstration of EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> for PFAS destruction in a concentrated waste stream in a Mid-Atlantic Naval Air Station: a) Target PFAS at each step of the treatment shows that about 99% of PFAS were destroyed; meanwhile, the final degradation product, i.e., fluoride, increased to 15 mg/L in concentration, demonstrating effective PFAS destruction; b) AOF concentrations at each step of the treatment provided additional evidence to show near-complete mineralization of PFAS. Average results from multiple batches of treatment are shown here.]] | |

| − | The | + | [[File: XiongFig3.png | thumb | 500 px | Figure 3. Field demonstration of a treatment train (SAFF + EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>) for groundwater PFAS separation and destruction at an Air Force base in California: a) Two main components of the treatment train, i.e. SAFF and EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>; b) Results showed the effective destruction of various PFAS in the foam fractionate. The target PFAS at each step of the treatment shows that about 99.9% of PFAS were destroyed. Meanwhile, the final degradation product, i.e., fluoride, increased to 30 mg/L in concentration, demonstrating effective destruction of PFAS in a foam fractionate concentrate. After a polishing treatment step (GAC) via the onsite groundwater extraction and treatment system, all PFAS were removed to concentrations below their MCLs.]] |

| − | + | The effectiveness of UV/sulfite technology for treating PFAS has been evaluated in two field demonstrations using the EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> system. Aqueous samples collected from the system were analyzed using EPA Method 1633, the [[Wikipedia: TOP Assay | total oxidizable precursor (TOP) assay]], adsorbable organic fluorine (AOF) method, and non-target analysis. A summary of each demonstration and their corresponding PFAS treatment efficiency is provided below. | |

| − | < | + | *Under the [https://serdp-estcp.mil/ Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP)] [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/4c073623-e73e-4f07-a36d-e35c7acc75b6/er21-5152-project-overview Project ER21-5152], a field demonstration of EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> was conducted at a Navy site on the east coast, and results showed that the technology was highly effective in destroying various PFAS in a liquid concentrate produced from an ''in situ'' foam fractionation groundwater treatment system. As shown in Figure 2a, total PFAS concentrations were reduced from 17,366 micrograms per liter (µg/L) to 195 µg/L at the end of the UV/sulfite reaction, representing 99% destruction. After the ion exchange resin polishing step, all residual PFAS had been removed to the non-detect level, except one compound (PFOS) reported as 1.5 nanograms per liter (ng/L), which is below the current Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) of 4 ng/L. Meanwhile, the fluoride concentration increased up to 15 milligrams per liter (mg/L), confirming near complete defluorination. Figure 2b shows the adsorbable organic fluorine results from the same treatment test, which similarly demonstrates destruction of 99% of PFAS. |

| + | *Another field demonstration was completed at an Air Force base in California, where a treatment train combining [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/263f9b50-8665-4ecc-81bd-d96b74445ca2 Surface Active Foam Fractionation (SAFF)] and EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> was used to treat PFAS in groundwater. As shown in Figure 3, PFAS analytical data and fluoride results demonstrated near-complete destruction of various PFAS. In addition, this demonstration showed: a) high PFAS destruction ratio was achieved in the foam fractionate, even in very high concentration (up to 1,700 mg/L of booster), and b) the effluent from EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> was sent back to the influent of the SAFF system for further concentration and treatment, resulting in a closed-loop treatment system and no waste discharge from EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>. This field demonstration was conducted with the approval of three regulatory agencies (United States Environmental Protection Agency, California Regional Water Quality Control Board, and California Department of Toxic Substances Control). | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 14:14, 11 February 2026

In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE)

The in situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation system is a tool to incorporate into weight-of-evidence studies at sites with numerous chemical toxicant classes present. The technology works by continuously sampling site water, immediately fractionating the water using diagnostic sorptive resins, and then exposing test organisms to the water to observe toxicity responses with minimal sample manipulation. It is compatible with various resins, test organisms, and common acute and chronic toxicity tests, and can be deployed at sites with a wide variety of physical and logistical considerations.

Related Article(s):

Contributors: Dr. G. Allen Burton Jr., Austin Crane

Key Resources:

- A Novel In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) System for Determining which Chemicals Drive Impairments at Contaminated Sites[1]

- An in situ toxicity identification and evaluation water analysis system: Laboratory validation[2]

- Sediment Toxicity Identification Evaluation (TIE) Phases I, II, and III Guidance Document- [3]

- In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) Technology for Assessing Contaminated Sediments, Remediation Success, Recontamination and Source Identification- [4]

Introduction

In waterways impacted by numerous naturally occurring and anthropogenic chemical stressors, it is crucial for environmental practitioners to be able to identify which chemical classes are causing the highest degrees of toxicity to aquatic life. Previously developed methods, including the Toxicity Identification Evaluation (TIE) protocol developed by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)[5], can be confounded by sample manipulation artifacts and temporal limitations of ex situ organism exposures[1]. These factors may disrupt causal linkages and mislead investigators during site characterization and management decision-making. The in situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) technology was developed to allow users to strengthen stressor-causality linkages and rank chemical classes of concern at impaired sites, with high degrees of ecological realism.

The technology has undergone a series of improvements in recent years, with the most recent prototype being robust, operable in a wide variety of site conditions, and cost-effective compared to alternative site characterization methods[6][7][1][2]. The latest prototype can be used in any of the following settings: in marine, estuarine, or freshwater sites; to study surface water or sediment pore water; in shallow waters easily accessible by foot or in deep waters only accessible by pier or boat. It can be used to study sites impacted by a wide variety of stressors including ammonia, metals, pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), among others. The technology is applicable to studies of acute toxicity via organism survival or of chronic toxicity via responses in growth, reproduction, or gene expression[1].

System Components and Validation

The latest iTIE prototype consists of an array of sorptive resins that differentially fractionate sampled water, and a series of corresponding flow-through organism chambers that receive the treated water in situ. Resin treatments can be selected depending on the chemicals suspected to be present at each site to selectively sequester certain chemical of concern (CoC) classes from the whole water, leaving a smaller subset of chemicals in the resulting water fraction for chemical and toxicological characterization. Test organism species and life stages can also be chosen depending on factors including site characteristics and study goals. In the full iTIE protocol, site water is continuously sampled either from the sediment pore spaces or the water column at a site, gently oxygenated, diverted to different iTIE units for fractionation and organism exposure, and collected in sample bottles for off-site chemical analysis (Figure 1). All iTIE system components are housed within waterproof Pelican cases, which allow for ease of transport and temperature control.

Porewater and Surface Water Collection Sub-system

Given the importance of sediment porewater to ecosystem structure and function, investigators may employ the iTIE system to evaluate the toxic effects associated with the impacted sediment porewater. To accomplish this, the iTIE system utilizes the Trident probe, originally developed for Department of Defense site characterization studies[8]. The main body of the Trident is comprised of a stainless-steel frame with six hollow probes (Figure 2). Each probe contains a layer of inert glass beads, which filters suspended solids from the sampled water. The water is drawn through each probe into a composite manifold and transported to the rest of the iTIE system using a high-precision peristaltic pump.

The Trident also includes an adjustable stopper plate, which forms a seal against the sediment and prevents the inadvertent dilution of porewater samples with surface water. (Figure 2). Preliminary laboratory results indicate that the Trident is extremely effective in collecting porewater samples with minimal surface water infiltration in sediments ranging from coarse sand to fine clay. Underwater cameras, sensors, passive samplers, and other auxiliary equipment can be attached to the Trident probe frame to provide supplemental data.

Alternatively, practitioners may employ the iTIE system to evaluate site surface water. To sample surface water, weighted intake tubes can collect surface water from the water column using a peristaltic pump.

Advantages

A UV/sulfite treatment system offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction compared to other technologies, including high defluorination percentage, high treatment efficiency for short-chain PFAS without mass transfer limitation, selective reactivity by eaq-, low energy consumption, and the production of no harmful byproducts. A summary of these advantages is provided below:

- High efficiency for short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS: While the degradation efficiency for short-chain PFAS is challenging for some treatment technologies[9][10][11], the UV/sulfite process demonstrates excellent defluorination efficiency for both short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS, including trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and perfluoropropionic acid (PFPrA).

- High defluorination ratio: As shown in Figure 3, the UV/sulfite treatment system has demonstrated near 100% defluorination for various PFAS under both laboratory and field conditions.

- No harmful byproducts: While some oxidative technologies, such as electrochemical oxidation, generate toxic byproducts, including perchlorate, bromate, and chlorate, the UV/sulfite system employs a reductive mechanism and does not generate these byproducts.

- Ambient pressure and low temperature: The system operates under ambient pressure and low temperature (<60°C), as it utilizes UV light and common chemicals to degrade PFAS.

- Low energy consumption: The electrical energy per order values for the degradation of perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs) by UV/sulfite have been reduced to less than 1.5 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per cubic meter under laboratory conditions. The energy consumption is orders of magnitude lower than that for many other destructive PFAS treatment technologies (e.g., supercritical water oxidation)[12].

- Co-contaminant destruction: The UV/sulfite system has also been reported effective in destroying certain co-contaminants in wastewater. For example, UV/sulfite is reported to be effective in reductive dechlorination of chlorinated volatile organic compounds, such as trichloroethene, 1,2-dichloroethane, and vinyl chloride[13][14][15][16].

Limitations

Several environmental factors and potential issues have been identified that may impact the performance of the UV/sulfite treatment system, as listed below. Solutions to address these issues are also proposed.

- Environmental factors, such as the presence of elevated concentrations of natural organic matter (NOM), dissolved oxygen, or nitrate, can inhibit the efficacy of UV/sulfite treatment systems by scavenging available hydrated electrons. Those interferences are commonly managed through chemical additions, reaction optimization, and/or dilution, and are therefore not considered likely to hinder treatment success.

- Coloration in waste streams may also impact the effectiveness of the UV/sulfite treatment system by blocking the transmission of UV light, thus reducing the UV lamp's effective path length. To address this, pre-treatment may be necessary to enable UV/sulfite destruction of PFAS in the waste stream. Pre-treatment may include the use of strong oxidants or coagulants to consume or remove UV-absorbing constituents.

- The degradation efficiency is strongly influenced by PFAS molecular structure, with fluorotelomer sulfonates (FTS) and perfluorobutanesulfonate (PFBS) exhibiting greater resistance to degradation by UV/sulfite treatment compared to other PFAS compounds.

State of the Practice

The effectiveness of UV/sulfite technology for treating PFAS has been evaluated in two field demonstrations using the EradiFluorTM[17] system. Aqueous samples collected from the system were analyzed using EPA Method 1633, the total oxidizable precursor (TOP) assay, adsorbable organic fluorine (AOF) method, and non-target analysis. A summary of each demonstration and their corresponding PFAS treatment efficiency is provided below.

- Under the Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP) Project ER21-5152, a field demonstration of EradiFluorTM[17] was conducted at a Navy site on the east coast, and results showed that the technology was highly effective in destroying various PFAS in a liquid concentrate produced from an in situ foam fractionation groundwater treatment system. As shown in Figure 2a, total PFAS concentrations were reduced from 17,366 micrograms per liter (µg/L) to 195 µg/L at the end of the UV/sulfite reaction, representing 99% destruction. After the ion exchange resin polishing step, all residual PFAS had been removed to the non-detect level, except one compound (PFOS) reported as 1.5 nanograms per liter (ng/L), which is below the current Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) of 4 ng/L. Meanwhile, the fluoride concentration increased up to 15 milligrams per liter (mg/L), confirming near complete defluorination. Figure 2b shows the adsorbable organic fluorine results from the same treatment test, which similarly demonstrates destruction of 99% of PFAS.

- Another field demonstration was completed at an Air Force base in California, where a treatment train combining Surface Active Foam Fractionation (SAFF) and EradiFluorTM[17] was used to treat PFAS in groundwater. As shown in Figure 3, PFAS analytical data and fluoride results demonstrated near-complete destruction of various PFAS. In addition, this demonstration showed: a) high PFAS destruction ratio was achieved in the foam fractionate, even in very high concentration (up to 1,700 mg/L of booster), and b) the effluent from EradiFluorTM[17] was sent back to the influent of the SAFF system for further concentration and treatment, resulting in a closed-loop treatment system and no waste discharge from EradiFluorTM[17]. This field demonstration was conducted with the approval of three regulatory agencies (United States Environmental Protection Agency, California Regional Water Quality Control Board, and California Department of Toxic Substances Control).

References

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Burton, G.A., Cervi, E.C., Meyer, K., Steigmeyer, A., Verhamme, E., Daley, J., Hudson, M., Colvin, M., Rosen, G., 2020. A novel In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) System for Determining which Chemicals Drive Impairments at Contaminated Sites. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 39(9), pp. 1746-1754. doi: 10.1002/etc.4799

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Steigmeyer, A.J., Zhang, J., Daley, J.M., Zhang, X., Burton, G.A. Jr., 2017. An in situ toxicity identification and evaluation water analysis system: Laboratory validation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 36(6), pp. 1636-1643. doi: 10.1002/etc.3696

- ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2007. Sediment Toxicity Identification Evaluation (TIE) Phases I, II, and III Guidance Document, EPA/600/R-07/080. 145 pages. Free Download Report.pdf

- ^ In Situ Toxicity Identification Evaluation (iTIE) Technology for Assessing Contaminated Sediments, Remediation Success, Recontamination and Source Identification Project Website Final Report.pdf

- ^ Norberg-King, T., Mount, D.I., Amato, J.R., Jensen, D.A., Thompson, J.A., 1992. Toxicity identification evaluation: Characterization of chronically toxic effluents: Phase I. Publication No. EPA/600/6-91/005F. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development. Free Download from US EPA Report.pdf

- ^ Burton, G.A. Jr., Nordstrom, J.F., 2004. An in situ toxicity identification evaluation method part I: Laboratory validation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(12), pp. 2844-2850. doi: 10.1897/03-409.1

- ^ Burton, G.A. Jr., Nordstrom, J.F., 2004. An in situ toxicity identification evaluation method part II: Field validation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(12), pp. 2851-2855. doi: 10.1897/03-468.1

- ^ Chadwick, D.B., Harre, B., Smith, C.F., Groves, J.G., Paulsen, R.J., 2003. Coastal Contaminant Migration Monitoring: The Trident Probe and UltraSeep System. Hardware Description, Protocols, and Procedures. Technical Report 1902. Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center.

- ^ Singh, R.K., Brown, E., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2021. Treatment of PFAS-containing landfill leachate using an enhanced contact plasma reactor. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 408, Article 124452. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452

- ^ Singh, R.K., Multari, N., Nau-Hix, C., Woodard, S., Nickelsen, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2020. Removal of Poly- and Per-Fluorinated Compounds from Ion Exchange Regenerant Still Bottom Samples in a Plasma Reactor. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(21), pp. 13973-80. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02158

- ^ Nau-Hix, C., Multari, N., Singh, R.K., Richardson, S., Kulkarni, P., Anderson, R.H., Holsen, T.M., Mededovic Thagard S., 2021. Field Demonstration of a Pilot-Scale Plasma Reactor for the Rapid Removal of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Groundwater. American Chemical Society’s Environmental Science and Technology (ES&T) Water, 1(3), pp. 680-87. doi: 10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170

- ^ Nzeribe, B.N., Crimi, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holsen, T.M., 2019. Physico-Chemical Processes for the Treatment of Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): A Review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 49(10), pp. 866-915. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2018.1542916

- ^ Jung, B., Farzaneh, H., Khodary, A., Abdel-Wahab, A., 2015. Photochemical degradation of trichloroethylene by sulfite-mediated UV irradiation. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 3(3), pp. 2194-2202. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2015.07.026

- ^ Liu, X., Yoon, S., Batchelor, B., Abdel-Wahab, A., 2013. Photochemical degradation of vinyl chloride with an Advanced Reduction Process (ARP) – Effects of reagents and pH. Chemical Engineering Journal, 215-216, pp. 868-875. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.11.086

- ^ Li, X., Ma, J., Liu, G., Fang, J., Yue, S., Guan, Y., Chen, L., Liu, X., 2012. Efficient Reductive Dechlorination of Monochloroacetic Acid by Sulfite/UV Process. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(13), pp. 7342-49. doi: 10.1021/es3008535

- ^ Li, X., Fang, J., Liu, G., Zhang, S., Pan, B., Ma, J., 2014. Kinetics and efficiency of the hydrated electron-induced dehalogenation by the sulfite/UV process. Water Research, 62, pp. 220-228. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.051

- ^ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedEradiFluor